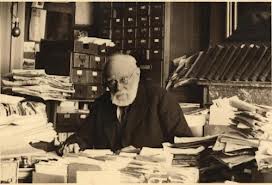

In 02007, SALT speaker Alex Wright introduced us to Paul Otlet, the Belgian visionary who spent the first half of the twentieth century building a universal catalog of human knowledge, and who dreamed of creating a global information network that would allow anyone virtual access to this “Mundaneum.”

In June of this year, Wright released a new monograph that examines the impact of Otlet’s work and dreams within the larger history of humanity’s attempts to organize and archive its knowledge. In Cataloging The World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age, Wright traces the visionary’s legacy from its idealistic mission through the Mundaneum’s destruction by the Nazis, to the birth of the internet and the data-driven world of the 21st century.

In June of this year, Wright released a new monograph that examines the impact of Otlet’s work and dreams within the larger history of humanity’s attempts to organize and archive its knowledge. In Cataloging The World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age, Wright traces the visionary’s legacy from its idealistic mission through the Mundaneum’s destruction by the Nazis, to the birth of the internet and the data-driven world of the 21st century.

Otlet’s work on his Mundaneum went beyond a simple wish to collect and catalog knowledge: it was driven by a deeply idealistic vision of a world brought into harmony through the free exchange of information.

An ardent “internationalist,” Otlet believed in the inevitable progress of humanity towards a peaceful new future, in which the free flow of information over a distributed network would render traditional institutions – like state governments – anachronistic. Instead, he envisioned a dawning age of social progress, scientific achievement, and collective spiritual enlightenment. At the center of it all would stand the Mundaneum, a bulwark and beacon of truth for the whole world. (Wright 02014)

Otlet imagined a system of interconnected “electric telescopes” with which people could easily access the Mundaneum’s catalog of information from the comfort of their homes – a ‘world wide web’ that would bring the globe together in shared reverence for the power of knowledge. But sadly, his vision was thwarted before it could reach its full potential. Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova writes,

At the peak of Otlet’s efforts to organize the world’s knowledge around a generosity of spirit, humanity’s greatest tragedy of ignorance and cruelty descended upon Europe. As the Nazis seized power, they launched a calculated campaign to thwart critical thought by banning and burning all books that didn’t agree with their ideology … and even paved the muddy streets of Eastern Europe with such books so the tanks would pass more efficiently.

Otlet’s dream of open access to knowledge obviously clashed with the Nazis’ effort to control the flow of information, and his Mundaneum was promptly shut down to make room for a gallery displaying Third Reich art. Nevertheless, Otlet’s vision survived, and in many ways inspired the birth of the internet.

While Otlet did not by any stretch of the imagination “invent” the Internet — working as he did in an age before digital computers, magnetic storage, or packet-switching networks — nonetheless his vision looks nothing short of prophetic. In Otlet’s day, microfilm may have qualified as the most advanced information storage technology, and the closest thing anyone had ever seen to a database was a drawer full of index cards. Yet despite these analog limitations, he envisioned a global network of interconnected institutions that would alter the flow of information around the world, and in the process lead to profound social, cultural, and political transformations. (Wright 02014)

Still, Wright argues, some characteristics of today’s internet fly in the face of Otlet’s ideals even as they celebrate them. The modern world wide web is predicated on an absolute individual freedom to consume and contribute information, resulting in an amorphous and decentralized network of information whose provenance can be difficult to trace. In many ways, this defies Otlet’s idealistic belief in a single repository of absolute and carefully verified truths, open access to which would lead the world to collective enlightenment. Wright wonders,

Still, Wright argues, some characteristics of today’s internet fly in the face of Otlet’s ideals even as they celebrate them. The modern world wide web is predicated on an absolute individual freedom to consume and contribute information, resulting in an amorphous and decentralized network of information whose provenance can be difficult to trace. In many ways, this defies Otlet’s idealistic belief in a single repository of absolute and carefully verified truths, open access to which would lead the world to collective enlightenment. Wright wonders,

Would the Internet have turned out any differently had Paul Otlet’s vision come to fruition? Counterfactual history is a fool’s game, but it is perhaps worth considering a few possible lessons from the Mundaneum. First and foremost, Otlet acted not out of a desire to make money — something he never succeeded at doing — but out of sheer idealism. His was a quest for universal knowledge, world peace, and progress for humanity as a whole. The Mundaneum was to remain, as he said, “pure.” While many entrepreneurs vow to “change the world” in one way or another, the high-tech industry’s particular brand of utopianism almost always carries with it an underlying strain of free-market ideology: a preference for private enterprise over central planning and a distrust of large organizational structures. This faith in the power of “bottom-up” initiatives has long been a hallmark of Silicon Valley culture, and one that all but precludes the possibility of a large-scale knowledge network emanating from anywhere but the private sector.

Nevertheless, Wright sees in Otlet’s vision a useful ideal to keep striving for:

Otlet’s Mundaneum will never be. But it nonetheless offers us a kind of Platonic object, evoking the possibility of a technological future driven not by greed and vanity, but by a yearning for truth, a commitment to social change, and a belief in the possibility of spiritual liberation. Otlet’s vision for an international knowledge network—always far more expansive than a mere information retrieval tool—points toward a more purposeful vision of what the global network could yet become. And while history may judge Otlet a relic from another time, he also offers us an example of a man driven by a sense of noble purpose, who remained sure in his convictions and unbowed by failure, and whose deep insights about the structure of human knowledge allowed him to peer far into the future…

Wright summarizes Otlet’s legacy with a simple question: are we better off when we safeguard the absolute individual freedom to consume and distribute information as we see fit, or should we be making a more careful effort to curate the information we are surrounded by? It’s a question that we see emerging with growing urgency in contemporary debates about privacy, data sharing, and regulation of the internet – and our answer to it is likely to play an important role in shaping the future of our information networks.

To learn more about Cataloging the World, please take a look at Maria Popova’s thoughtful review, or visit the book’s website.