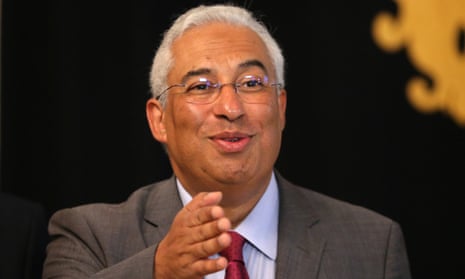

The Socialist leader Antonio Costa has been named Portugal’s prime minister and tasked with forming a government, more than seven weeks after an inconclusive general election plunged the country into political limbo.

His appointment comes after Costa’s alliance with Communist, Green and Left Bloc parties toppled an 11-day-old conservative minority government in a dramatic parliamentary vote – the shortest administration in Portuguese history.

Portugal’s political saga is being closely watched in Brussels as the country recovers from a €78bn bailout in 2011, with Costa seeking to allay fears over his vow to “turn the page on austerity”.

The centre-right bloc of the outgoing conservative prime minister, Pedro Passos, Coelho won the most seats in elections on 4 October but lost the absolute majority it had enjoyed since 2011.

By teaming up the leftist parties managed to assemble a slim parliamentary majority that allowed them to vote out Passos Coelho’s government on 11 November.

The newly formed leftist alliance – the first since the birth of democratic Portugal four decades ago – seemed inconceivable just weeks earlier as the parties struggled to work out their difficulties.

President Anibal Cavaco Silva, a conservative who was reluctant to hand power to a leftist coalition he views as “incoherent”, said it “would not have served the national interest” to leave Passos Coehlo in power as he named Costa as premier on Tuesday.

Costa, the former mayor of Lisbon, has insisted his government will meet international commitments on its budget and debts, a year and a half after it exited its bailout programme.

The 54-year-old has said his government will run “a socialist programme” that allows for “a sustainable reduction in deficits and debt”.

The Socialist leader had to give the president written guarantees that his government would maintain stability and respect European rules.

He ruled out leaving the euro or restructuring Portugal’s debt – but has also had to negotiate risky concessions with the radical left that will impact on his budget.

Planned measures include raising the minimum wage, lifting a freeze on pensions and cancelling pay cuts for civil servants due next year.

Despite the hostility of some members of the alliance – the communists and the left bloc – to Europe-imposed austerity, a clash between Lisbon and Brussels does not appear to be on the cards.

“We shouldn’t expect a confrontation because the experience with Greece has shown that this leads nowhere,” said political commentator Jose Antonio Passos Palmeira.

Portugal has still managed despite political instability to borrow at negative rates in a completely different economic context from when it was forced into a bailout.

Nevertheless the political situation was far from stable, warned Passos Palmeira.

“These are fragile alliances which allow Antonio Costa to come to power but does not guarantee a sustainable government,” he said.

Costa certainly faces a challenge holding together a disparate group – suitable for a man who likes to relax by doing 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzles – but he seems confident.

“I always deliver more than I promise,” he declared, pointing to his record as mayor of Lisbon, where he was elected three times, with a bigger majority each time.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion