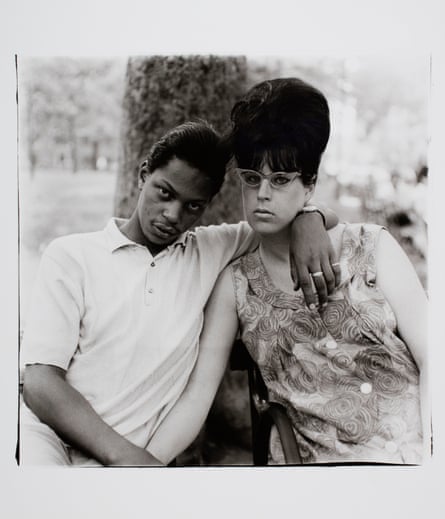

No one captured the chaos of the 1960s more acutely than Garry Winogrand. His voracious, omnipresent eye sought out the decade’s absurdities. He revealed the society balls of the 1%; the joy, violence and despair of marches, protests and parties; the spectacle of politics and press conferences, and the quotidian street. His work ventured far beyond what he regarded as the limitations of photojournalism, says Sophie Hackett, associate curator of photography at the Art Gallery of Ontario. “He very much strove to separate his image from the written word and embrace that ambiguity. He didn’t want a caption, he didn’t want a sequence, he didn’t want a narrative – he wanted a picture.”

The exhibition Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s, at the AGO in Toronto, takes Winogrand as the spiritual starting point for the radical photographic transformations that emerged from, and captured, the upheavals of post-war America. A featured exhibition in the 20th edition of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival which launches this week, it assembles 400 photos and five films by Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Gordon Parks, Danny Lyon, Kenneth Anger, Robert Frank and Shirley Clarke among others.

While such iconic art has its own pleasures – how can one ever tire of an Arbus portrait? – the challenge of a curator is to make the familiar strange again. Using a thematic organization, co-curators Hackett and Jim Shedden tease out fresh complexities from this famed visual moment. To look at the past always begs the question of the present from which we look, and these works resonate with current movements, particularly Black Lives Matter and transgender rights, as well as our physical and psychological integration of photography.

Following a loose chronology, the exhibition seeks out contradictions and parallels. Next to Winogrand is Gordon Parks’s Life magazine photo essay documenting the Fontenelle family’s poverty in Harlem from 1968. This is the narrative style Winogrand was escaping from, one of individual characters, and agendas. With their almost melodramatic use of light, Park’s essay, which sought to answer the question of why African Americans were rioting, struck a chord with its white, middle-class audience and are still deeply moving. Fifty years later, protesters are in the streets asserting that Black Lives Matter and demanding the same as Parks: “If you wish to turn my anger – the Negro’s anger – from you, acknowledge me and my needs.”

The dominance of Life and the other photo magazines declined in the late 60s and early 70s. Photography had also yet to be embraced by the art world, so this economic and philosophical vacuum – with echoes of our own digital disruption–required artists to innovate new ways of working. Arbus, despite being exhibited alongside Winogrand and Lee Friedlander in the landmark New Documents show at MoMA in 1967, saw little financial gain from the exposure – she only sold a few photos to collectors in her lifetime – and had to continue to work for magazines, though she managed to do so on her own terms. Winogrand pursued teaching; Danny Lyon turned to book publishing for his work on outlaw bikers; and Goldin first showed her photographic slideshow Ballad of Sexual Dependency in bars.

These decades also saw technological innovations like the home movie camera, the slide show, and the snapshot camera that fundamentally altered how we saw the world. As transgender artist Zackary Drucker points out: “What becomes known as a transgender experience emerges at the same time as an explosion in image-making.” The snapshot, because of its portability and domestic use, opened up more private realms, and one thread that runs through the exhibition is the diminishing distance between photographers and their subjects.

No images demonstrate this more powerfully than the Casa Susannah photographs. Taken during the mid 50s and 60s at a safe haven in New York state (and developed on site for total discretion), they show heterosexual men – though some transitioned later – dressed conservatively, glamming it up for the camera and creating alternative, everyday realities: eating dinner, doing their makeup, watering the lawn, reading. The trove was found at a flea market in New York City, released as a book in 2005, and were recently acquired by the AGO – they will also be displayed during the festival as murals and posters in the St Patrick subway station.

For Drucker, who is also a co-producer on Transparent, these photos do important archaeological work. “It’s so hard to locate the history of trans people, it’s such an oral history. We’ve really been concealed and hidden.” Some of the photos were circulated through Transvestia magazine or sent between participants, some as Christmas cards. The image, as it becomes society’s dominant medium, also becomes the medium of gender, and these photos create new, persuasive worlds in ways words cannot.

Michael Gilbert, a philosophy professor at York University and lifelong cross-dresser, says that in the current backlash of ridiculous bathroom laws, “The work itself is an argument for sympathy toward cross-dressers. It’s showing them doing things that are perfectly harmless. They’re enjoying themselves, they’re supporting each other, and collectively the photos form a case, they’re saying, look, you know, we’re repressing these people and for what reason?”

Goldin, of course, erases the distance between observer and subject in her images. How she turns makes public the private is foundational to our current use of photography. In her 1986 introduction to her book version of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, she writes, “It’s as if my hand were a camera.”

The sheer quantity of images, some 700, in the 42-minute slideshow presages the digital tidal wave just around the corner. And yet, given this glut and the passing of four decades, these photos haven’t lost any of their electricity; the raw and amped colors, the camaraderie, the sex, the joy and violence, can still turn one on or off. What’s powerful and fresh seems to come from the relationship – like in Arbus – between the artist and subject, whereas now the photographic act is often used to relate to those who are absent rather than present.

The slideshow changed with each showing and created a community around the artwork. When museums acquired it, what was meant to be durational and fluid then became fixed, says Jeff Rosenheim, photography curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Similarly, institutions are now struggling with how to collect and present new work. “The best photography being done today is in a purely digital format, and it’s all about communication between individuals or groups of individuals. How do we record that visual expression of our time, which is not about fixing the images in a physical space?” He doesn’t feel obliged to collect it, but he does want to share these alternative modes. “I think we’re in the midst of a new medium and if we don’t see it as that it’s only to our own detriment.”

Outsiders is at the Art Gallery of Ontario until 29 May and the CONTACT festival takes place throughout Toronto for the month of May. Jeff Rosenheim will speak about Diane Arbus on 6 May, Zackary Drucker and Michael Gilbert about Casa Susanna on 11 May, and LaToya Ruby Frazier about Gordon Parks on 27 May.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion