The Younger Victims of Sexual Violence in School

Conversations about Title IX tend to focus on college, but cases among K-12 students are abundant and often poorly handled.

After telling school officials she was raped in the band room, Rachel Bradshaw-Bean was punished. Instead of receiving protection from leaders at her Texas high school, she was kicked out and shipped off to an alternative school—alongside the boy she said attacked her.

In California, 13-year-old Seth Walsh killed himself after telling classmates he was gay. Walsh faced two years of relentless and escalating harassment after coming out, investigators said, but school officials failed to address the abuse until it was too late. In 2010, he hanged himself.

In both of those cases, the K-12 school districts reached agreements with the U.S. Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights, after federal investigators found local education officials had failed their obligation to protect students from gender-based violence under Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination in schools. In each case, district leaders promised they’d create new school policies to better protect student safety.

Adele Kimmel is banking on a similar outcome for her client. A Washington, D.C.-based senior attorney at Public Justice, Kimmel has for several years been representing sexual-violence victims, including a young Georgia woman who allegedly also faced retaliation for reporting an attack. Inside a Gwinnett County high school’s newsroom, Kimmel said, a male classmate coerced the young woman into performing oral sex. After she reported the purported incident to school officials, she was suspended for engaging in sexual acts on campus. But first, Kimmel contended, educators grilled her client with bone-chilling questions: “What were you wearing?” “Why didn’t you scream louder?”

Gwinnett County Public Schools is currently one of 137 K-12 school districts under investigation by the Office for Civil Rights for 154 Title IX sexual-violence complaints, according to a spreadsheet, dated August 2, the department provided to The74Million.org, which published this story in partnership with The Atlantic. The pending investigations—against public districts, private institutions, and charter school networks in 37 states and the District of Columbia—stretch back as far as December 2010. On the university level, the office currently has 350 investigations pending at 246 postsecondary institutions, according to an Education Department spreadsheet also dated August 2.

“What you see most commonly is that colleges are far ahead of K-12 schools in the development of their sexual-misconduct policies and procedures, their training, and their education of staff and students, making sure that students know who the Title IX coordinator is,” Kimmel said. “My concern is that—with the changes that seem to be coming from the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights—K-12 schools are going to fall even further behind in terms of Title IX compliance.”

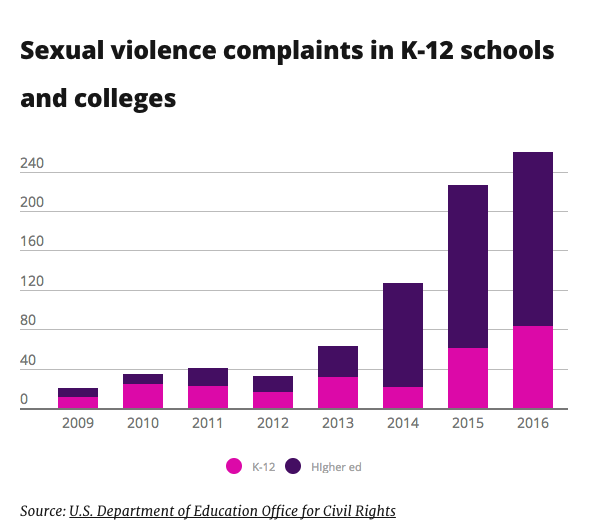

Victims of sexual assault on college campuses found a national platform as the Obama administration placed a clear focus on Title IX enforcement, most notably for articulating the evidentiary standard for findings of wrongdoing in campus sexual-violence cases. While K-12 schools have largely been left out of the debate, in recent years the Office for Civil Rights has seen a surge in Title IX complaints against these schools similar to those targeted at colleges and universities.

Following a series of July listening sessions with victims of sexual violence, students who say they were unfairly punished under Title IX, and education leaders, DeVos is contemplating a philosophical and practical shift at the department’s civil-rights division, which the new administration plans to revive as a “neutral, impartial, investigative agency.” “A system without due process ultimately serves no one in the end,” DeVos said.

“There are some things that are working. There are many things that are not working well,” she told reporters. “We need to get this right.”

Obama-era Title IX guidance has been a thorn for Republican lawmakers and advocates who have alleged—including in lawsuits—that the former administration stripped due-process rights from students accused of sexual harassment and assault. At the heart of that complaint is a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter that urged colleges and K-12 schools to better investigate reports of sexual violence, specifying that educators “must use a preponderance of the evidence standard” in campus investigations, rather than the more rigorous “clear and convincing” standard. Advocates for sexual-assault victims note the “preponderance of the evidence” standard is used to adjudicate other civil-rights claims, including discrimination.

Jayne Ellspermann, a former principal in Florida, acknowledged that while K-12 leaders across the country have an obligation to ensure students are safe on school grounds, districts vary in their sexual-assault-prevention measures. Some have robust supports with clear guidelines and procedures, she said, but in other communities “this situation might not have ever occurred and they don’t have a framework to work with.”

She said federal oversight is beneficial for communities lacking strong procedures, but “the local level is the most appropriate” place for situations to be handled. “We need to trust the schools and law enforcement and the local social-service agencies to do their jobs to support students and schools in situations like this,” said Ellspermann, who recently completed a one-year stint as the president of the National Association of Secondary School Principals.

In response to potential policy shifts under the DeVos administration, Ellspermann said it’s important to “to look at different procedures and ensure that they are appropriate for the current day and time.”

Gwinnett County Public Schools did not respond to requests for comment. Naomi Gittins, the managing director of the National School Boards Association, and Phillip Hartley, its vice chair, were listed among those who attended a Title IX listening session with DeVos, but neither responded to requests for comment. Francisco Negron, the group’s chief legal officer, could not be reached for comment.

After the Obama administration released its 2011 guidance, Negron raised several concerns, joining the ranks of some college officials who have argued it’s vague and inconsistent. The department, he told Education Week, needed to better clarify when an off-campus incident should prompt school-district intervention.

“Say the allegations haven’t been proven,” Negron said at the time. “It’s not clear from the department’s guidance what the district’s responsibility would be.”

The prevalence of child sexual abuse is difficult to pinpoint because victims often do not report the attack, though studies have shown about 20 percent of girls and over 5 percent of boys are victims of sexual abuse. In fact, 44 percent of attacks take place before the victim enrolls in college. And children who experience sexual violence are nearly 14 times more likely to experience rape or attempted rape in their first year of college, according to the National Center for Victims of Crime.

More than half of attacks occur at or near the victim’s home, and 8 percent take place on school property, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network.

In the first year of Obama’s presidency, in 2009, the Office for Civil Rights received just 11 Title IX sexual-violence complaints against K-12 schools, according to federal figures. That number jumped to 83 in 2016, totaling 269 K-12 complaints over the eight-year period.

Officials at the Office for Civil Rights also resolved 371 sexual-violence complaints against K-12 schools and colleges, with investigations often taking up to several years to complete. Among cases resolved was a compliance review of California’s West Contra Costa Unified School District, where federal officials concluded following a 2009 high-school gang rape that sexual harassment among students “permeated the district’s elementary and secondary schools.”

Despite the sharp increase in complaints, the numbers don’t indicate a surge in sexual violence, Catherine Lhamon, the Education Department’s assistant secretary for civil rights under Obama, told The 74 in June. Rather, she said, the increase suggests more and more people saw OCR as an avenue for relief. Nationally, the rate of sexual assault and rape in general has fallen more than 60 percent in the last two decades. Although research has varied, studies suggest between 2 percent and 8 percent of sexual-assault complaints are false.

“Also, there was a galvanizing movement around the country of securing change on those topics, and so it prompted more people to feel safe coming forward,” Lhamon said. “Over too many decades, sexual harassment and sexual violence have been categories of shame for people who have experienced them, and it has been hard for them to come forward.”

In the late 1990s, the U.S. Supreme Court issued two rulings that set standards for when schools and colleges can be held liable under Title IX for failing to prevent student-on-student and teacher-on-student sexual harassment and assault.

Yet at the high-school level, more than 80 percent of guidance counselors feel ill-equipped to address reports of abuse, according to Break the Cycle, an organization that addresses teen dating violence. “I wish I was seeing a trend where schools are becoming increasingly knowledgeable and better trained in the K-12 setting, but I’m not,” said the Michigan-based attorney Monica Beck of the Fierberg National Law Group. “I think a lot of people don’t understand the prevalence of sexual assault in this country’s schools.”

Along with defining the evidentiary standard, Obama-era guidance documents directed districts to hire Title IX coordinators to oversee compliance, promptly investigate and resolve complaints, and provide reasonable accommodations to victims so they can pursue an education in a safe environment. Failure to comply, the department noted, could cost a district its federal funds—an extreme measure that’s never been used against either a K-12 school or a college or university.

Generally, districts sign voluntary resolution agreements and promise changes if the Office for Civil Rights finds they aren’t compliant with the law, as was the case with Rachel Bradshaw-Bean’s district in Henderson, Texas, and Sean Walsh’s district in Tehachapi, California.

In the last few months, the Trump administration has already shown Obama-era guidance letters are easily reversed. In February, the Departments of Education and Justice rescinded an Obama-era “Dear Colleague” letter that said Title IX prohibits discrimination based on gender identity, not just a student’s sex at birth.

Former Obama education officials maintain, however, that reversing guidance letters won’’t change the protections and legal obligations laid out in Title IX.

Even as the Georgia student waits for the Education Department to reach a verdict in her case, her reporting has already prompted changes in Gwinnett County schools, Kimmel said. For example, the district now has a website that identifies its Title IX coordinators and district policies. A ruling could force additional changes.

After the student filed a complaint with the office, investigators launched a compliance review, Kimmel said, which looks at three years of district complaint records to determine whether systemic civil-rights violations existed. “Part of the reason that students will file these complaints is that they’re looking to make changes so nobody else goes through what they did,” she said.

Under DeVos, however, the Office for Civil Rights has already laid out plans to roll back that review process, according to an internal memo sent by Candice Jackson, the acting head of OCR, and obtained by ProPublica.

In a statement, an Education Department spokesman said the office will use a “systemic” or “class-action” approach to investigations only if a complainant raises widespread issues or the department determines such issues exist through conversations with the complainant.

If the office limits or narrows its enforcement of Title IX, Kimmel said, victims may feel less empowered to report incidents because of a “chilling effect.” Requiring the “clear and convincing evidence” standard, she said, could make victims feel less empowered to report attacks if it’s harder to ensure their perpetrator is held accountable.

Christopher Perry, deputy executive director of Stop Abusive and Violent Environments, sees things differently.

He said he hopes the department replaces the current guidance with procedures similar to recent recommendations by an American Bar Association task force which, in some circumstances, seeks a higher standard of proof.

“What we’re trying to do is really put together a fair system that allows both parties to feel as though they were treated respectfully and that the outcome is reliable,” Perry said. “We want a full and fair investigation, we want both sides to be able to have adequate and timely notice of what’s going on. We would like a transparent hearing process.” He pointed to complaints from victims alleging that schools dismissed their cases without investigating them.

For that very reason—K-12 districts often fail to investigate complaints—changing the evidentiary standard may not have a huge effect on Beck’s work, she said, because she generally pursues justice through the courts, including in three pending cases. Among them, Beck represents four young women who say they were assaulted by former Major League Baseball Player Chad Curtis, who worked as a substitute teacher and volunteer weight-training instructor at a Michigan school district. In a 2013 criminal case, Curtis was found guilty of assaulting three of the young women.

Any change to the department’s Title IX guidance, however, could have ramifications for K-12 schools, Beck said.

“If the Department of Education even kind of takes its focus off of it, I can see that being very harmful to our nation’s students,” she said. “It’s really important, not only for schools to understand what their responsibilities are, but for students and parents to know what their rights are.”

This story was produced in collaboration with The74Million.org.