/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34894247/6626163537_15cbb77be1_o.0.jpg)

America is built around cars. And most of us expect that we'll be able to park our cars for free, pretty much anywhere we go.

But economist Donald Shoup of UCLA has made a name for himself by advocating an alternative scheme: charging for street parking anywhere there are more people with cars than spaces to park.

Shoup's 2005 book, The High Cost of Free Parking, articulated why exactly he thinks free parking is such a bad idea. His ideas have started to influence policy: several cities, including San Francisco, have recently begun experimenting with the variable, market-set pricing scheme he thinks makes the most sense. And recent studies have confirmed that it cuts down on cruising time and traffic congestion.

Shoup recently spoke with me to explain his argument in detail.

Parking isn't a public good — and isn't used by everyone

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images

Over the past century, we've come to regard parking as a basic public good that should be freely shared — partly because of the sheer historical accident that parking meters didn't come along until the 1930s, a few decades after the car.

"By then, the custom of free parking was well-established," Shoup says. "It's hard to start charging people for something that the government owns and had been free." Consequently, parking is still free, he calculates, for 99 percent of all car trips made in the country.

But a parking spot, unlike things we normally consider to be public goods, is finite. It can only be used by a one car at a time. So if we let the market set the price, in cities, it'd certainly go above zero — and there's not really any compelling reason why it alone should be kept free. "We pay for everything else about our cars — the car itself, the gas, the tires, the insurance," Shoup says. "Why is it that parking should be different?"

One counterexample you might point to are roads, which are ostensibly free public goods. But there are mechanisms in place, such as the gas tax, that try to ensure roads are largely paid for by automobile users, in proportion to their use of it. The gas tax system may be broken, but it still reflects the idea that car drivers should pay for the roads.

When we find an open spot on the street, and there's no meter, it seems free — but it too is the result of government spending. The cost of the land, pavement, street cleaning, and other services related to free parking spots come directly out of tax dollars (usually municipal or state funding sources). Each on-street parking space is estimated to cost around $1,750 to build and $400 to maintain annually.

"That parking doesn't just come out of thin air," Shoup says. "So this means people who don't own cars pay for other peoples' parking. Every time you walk somewhere, or ride a bike, or take a bus, you're getting shafted."

All our free street parking also leads to secondary problem: most city governments (with the exception of New York, San Francisco, and a few other dense cities) require all new buildings to include specified large numbers of added parking spaces — partly because otherwise, the free street parking would be swamped by new residents. "In most of the country, you can't build a new apartment building without two parking spaces per unit," Shoup says.

This too costs money. In Washington DC, the underground spots many developers build to comply with these minimum requirements cost between $30,000 and $50,000 each. Whether they're constructed along with apartment buildings or shopping complexes, this cost ultimately gets passed along to consumers, in the form of rent or the price of goods.

"Wherever you go — a grocery store, say — a little bit of the money you pay for products is siphoned away to pay for parking," Shoup says. "My idea is simple: if somebody doesn't have a car, they shouldn't have to pay for parking."

If just the way we paid for free parking were unfair, it might not be all that big of a deal. But there are a few totally unrelated and negative consequences of keeping parking free.

Free parking forces people to cruise for spots, subsidizes driving, and is bad way to allocate land

In many urban areas with high parking demand, when we subsidize its cost and freeze its apparent price at zero, there are many more people who want it than spots available. Without meters to stimulate turnover, people tend to take spots and hold on to them all day. As a result, we waste our time cruising, looking for scarce open space.

"When you have people driving around looking for parking, this adds to traffic congestion and carbon emissions," Shoup says. This effect isn't trivial: Shoup has estimated that in a 15-block area in Los Angeles' Westwood Village alone, cars travel about 950,000 miles annually just cruising for parking, burning 47,000 gallons of gasoline and emitting 730 tons of carbon dioxide.

There's also evidence that the free parking subsidy increases the demand for parking and the total number of miles driven — not just those driven while people cruise. A recent study found that people who live in residences in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx that have minimum parking requirements are significantly more likely to drive to work in Manhattan (compared to others who live and work in the same areas). Another study found that among dense American cities, public transit use is significantly higher where parking is more expensive.

In total, Shoup has estimated the annual free parking subsidy to cars to be as much as $127 billion nationally. For daily commuters that park free, this subsidy can be worth more than the cost of driving, on a per-mile basis. And by driving down the price of parking this heavily, we're giving everyone lots of incentive to rely on cars as often as possible, packing them in to crowded city areas and making it harder for everyone to drive and park.

Downtown Buffalo, New York, a city that's recently eliminated minimum parking requirements due to excess parking. CityLab

Finally, by mandating that developers build many spots of free parking to accompany all new developments — instead of letting demand determine how much parking is necessary — parking minimum requirements often end up wasting space on unnecessary empty lots and garages.

This hurts cities as a whole: in using space for parking instead of tax-paying business, a recent study found, the city of Hartford gives up about $1,200 in tax revenue per parking spot annually, for a total loss of $50 million. In some cities, huge percentages of increasingly empty downtowns have been given over to surface lots in order to comply with these requirements.

Free parking stimulates car-based development that hurts the poor

RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images

The main argument for free parking is that charging for it is effectively a regressive tax, because it disproportionately affects people with lower incomes. Spending on parking represents a larger percentage of their budget — and because having to pay for parking might price some lower income people out of their cars.

But currently, people who don't own cars are disproportionately lower income. Every tax dollar they spend that goes towards parking infrastructure is a more direct and regressive tax than what would be levied on car-owning people if they always had to pay for parking.

Additionally, having an abundance of free parking — and requiring it to be built along with all new developments — spurs the design of cities that depend wholly on cars, making it more difficult for people who can't afford cars to get around.

"The worst thing that many American cities have done, for low-income people, is create a world in which you need a car," Shoup says. "Parking pushes everything farther apart, and even if you're too poor to own a car, you have to pay for all the free parking you don't use."

Shoup contrasts Los Angeles' Walt Disney Concert Hall, which was required to be built with fifty times more parking spots than San Francisco's Louise Davies Hall. "Those kinds of decisions, made enough times, make the two cities look very different," he says.

Obviously, some people might prefer the car-friendly landscape of Los Angeles to the dense downtown of San Francisco, and there'd be nothing wrong with that. But currently, municipal parking requirements aren't even letting people make the choice: they're forcing it upon them, by requiring developers to surround every new building with seas of parking, whether at the surface level or underground.

So what's a better option for parking?

To cities where he serves as a parking consultant, Shoup's recommendation is simple. "Charge the right price for on-street parking," he says. "I see this as the lowest price you can charge and still have one or two open spaces per block." This means the market sets the price — and people are paying as little as possible for parking without creating the cruising problem.

Modern technology makes this easier than you might imagine. Three years ago, the city of San Francisco installed sensors in the pavement of 256 blocks' parking spaces, in order to calculate the spots' occupancy rates and vary the pricing based on it.

A real time map of parking costs in specific blocks is available online. SFPark

Every six months, they've adjusted the price of spots on each block, using wifi-connected meters. If more than 80 percent of the spots on a block are occupied in a given time slot, per hour parking prices go up 25 cents, and if less than 60 percent are, it goes down by 25 cents.

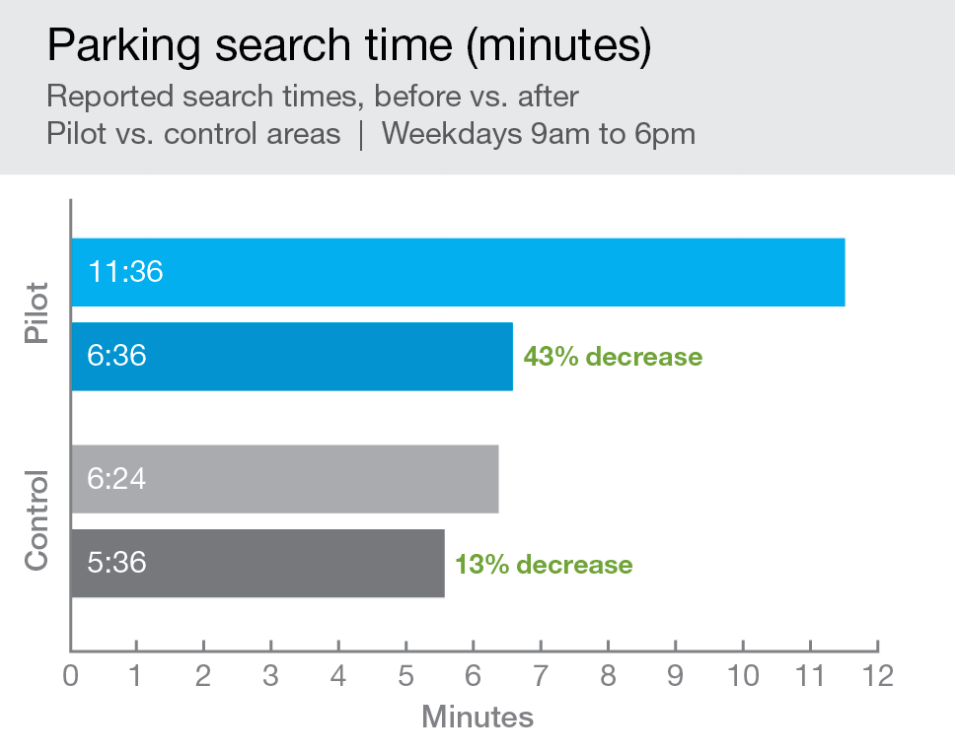

A study published in March (with which Shoup wasn't involved) found that the new scheme cut cruising in half, compared to a 55-block control area with fixed meter prices. A city study found that the total amount of driving in these areas fell by 30 percent — as people spent less time circling for spots — and that parking citations and double parking also fell. The effect is also visible when you compare the parking availability on these blocks before and after 6 pm, when the variable meters are turned off — and cruising goes up dramatically.

"It's made parking easier," says Shoup. "Wherever you go, you see one or two open spaces on the block where you're headed. It made it quicker, in the sense that you didn't have to drive around looking for parking. And this reduced traffic congestion and carbon emissions."

He also suggests doing away with both minimum and maximum numbers of off street parking for new buildings. "I'm pro-choice," he says. "Let the developers build however many parking spots they want." This will let demand determine the area of a city given over to lots and garages. For drivers, it'll also make paying for street parking more palatable, as they won't already be paying for parking in their rent and in the price of goods.

Finally, he recommends that cities not just put new parking revenues into their general funds. "We should use the revenue in a very visible, flamboyant way — so people can see the meter money at work locally, and know that it's doing good for them," he says.

In Ventura, for example, parking revenue has been used to pay for public wifi and new street lighting. Pasadena has used it for all sorts of infrastructure improvements that Shoup credits with revitalizing its downtown shopping area. "In Pasadena, this has led people on a lot of streets to come out and say, 'we want meters,'" Shoup says.

Further reading:

- "Free Parking Comes At a Price": Tyler Cowen's New York Times column on this idea

- Shoup's 1997 article, "The High Cost of Free Parking," which inspired his book

- A trailer for the documentary "Parking Craters"

- Aerial photos of Buffalo then and now — pre (1902) and post (2011) takeover by parking lots