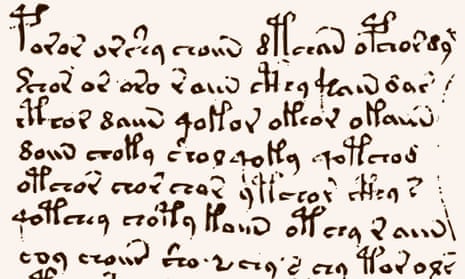

It’s one of the world’s most mysterious books, a centuries-old manuscript written in an unknown or coded language that no one has cracked.

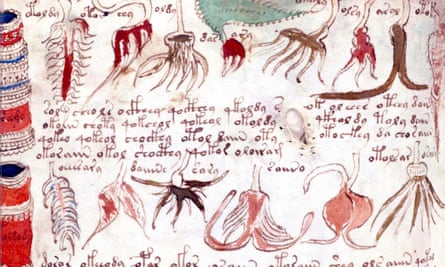

Scholars have spent their lives puzzling over the Voynich manuscript, whose intriguing mix of elegant writing and drawings of strange plants and naked women has some believing it holds magical powers.

The weathered book is locked away in a vault at Yale university’s Beinecke library, emerging only occasionally.

But after a 10-year appeal for access, Siloe, a small publishing house in northern Spain has secured the right to clone the document – to the delight of its director.

“Touching the Voynich is an experience,” says Juan Jose Garcia, sitting on the top floor of a book museum in the quaint centre of Burgos where Siloe’s office is, a few streets from the city’s famed Gothic cathedral.

“It’s a book that has such an aura of mystery that when you see it for the first time ... it fills you with an emotion that is very hard to describe.”

Siloe, which specialises in making facsimiles of old manuscripts, has bought the rights to make 898 exact replicas of the Voynich – so faithful that every stain, hole, sewn-up tear in the parchment will be reproduced.

The company always publishes 898 replicas of each work it clones – a number which is a palindrome – after the success of its first facsimile of which they made 696 copies.

The publishing house plans to sell the facsimiles for €7,000 to €8,000 (£6,000 to £6,900) apiece. Nearly 300 people have already put in pre-orders.

Raymond Clemens, curator at the Beinecke library, said Yale decided to have facsimiles done because of the many people who want to consult the fragile manuscript.

“We thought that the facsimile would provide the look and feel of the original for those who were interested,” he said.

“It also enables libraries and museums to have a copy for instructional purposes and we will use the facsimile ourselves to show the manuscript outside of the library to students or others who might be interested.”

The manuscript is named after antiquarian Wilfrid Voynich who bought it in about 1912 from a collection of books belonging to the Jesuits in Italy, and eventually propelled it into the public eye.

Theories abound about who wrote it and what it means.

For a long time, it was believed to be the work of 13th century English Franciscan friar Roger Bacon whose interest in alchemy and magic landed him in jail.

But that theory was discarded when the manuscript was carbon dated and found to have originated between 1404 and 1438.

Others point to a young Leonardo da Vinci, someone who wrote in code to escape the Inquisition, an elaborate joke or even an alien who left the book behind when leaving Earth.

The plants drawn have never been identified, the astronomical charts don’t reveal much. The women also offer few clues.

Scores have tried to decode the Voynich, including top cryptologists such as William Friedman who helped break Japan’s “Purple” cipher during the second world war.

The only person to have made any headway is Indiana Jones. The fictitious archeologist manages to crack it in a novel.

Fiction aside, the Beinecke library gets thousands of emails every month from people claiming to have decoded it, says Rene Zandbergen, a space engineer who runs a recognised blog on the manuscript, which he has consulted several times.

“More than 90% of all the access to their digital library is only for the Voynich manuscript,” he said.

Only slightly bigger than a paperback, the book contains more than 200 pages including several large fold-outs.

It will take Siloe about 18 months to make the first facsimiles, in a painstaking process that started in April when a photographer took detailed snaps of the original in Yale.

Workers at Siloe are now making mock-ups before they finally set about printing out the pages in a way that makes the script and drawings look like the real thing.

The paper they use – made from a paste developed by the company – has been given a special treatment so it feels like the stiff parchment used to write the Voynich.

Once printed, the pages are put together and made to look older.

All the imperfections are re-created using special tools in a process kept firmly secret by Garcia, who in his spare time has also tried his hand at cryptology.

“We call it the Voynich challenge,” he said.

“My business partner ... says the author of the Voynich could also have been a sadist, as he has us all wrapped up in this mystery.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion