Take note Labour: this is how you win an election. Jeremy Corbyn phone bank filling up 6 entire rooms pic.twitter.com/B18RV06jBc

— Charles B. Anthony (@CharlesBAnthony) August 19, 2015

Jeremy Corbyn is no ordinary politician. For his supporters that is his unique selling point, for his critics a terminal flaw. The former claim his leadership can offer a break with the current system, the latter that he is unable to even compete within the confines of the present one. What both sides do agree on is that Corbyn doesn’t look, or sound, like a prime minister. Were some future Hollywood blockbuster to include a British PM, it could foreseeably be David Cameron or Teresa May. ‘JC’? Well, that’s a little harder to imagine.

And it is that difficulty which has meant Corbyn’s tenure as leader of his party is now associated, among his detractors at least, with a single word: electability. For them, and this is a default presumption among liberal-left opinion (broadly the only kind permitted in the mainstream): Labour will never form a government – whether majority, minority or in coalition – with the member for Islington North in the top job.

During last summer’s leadership race, when the proposition of prime minister Corbyn was more abstract than real, the problem was his politics. That’s why, when he won, the membership was blamed as much as the man himself. The base, we were told, had lazily chosen its comfort zone and a return to the 1980s over the challenges of government. For Corbyn read Michael Foot. The next general election? A repeat of 1983.

And yet claims of Corbyn’s policies being out of kilter with the public have fallen away, particularly since Brexit. When former cabinet minister Stephen Crabb made a tilt for the Tory leadership recently – winning thirty four nominations in the first round – he did so on the promise of a £100 billion stimulus to the economy, in the process arguing for greater economic interventionism than Ed Miliband and the majority of the parliamentary Labour party. A fortnight later, and it seems almost certain that Theresa May’s government, given the likely recession Brexit will cause, will now pursue a program of fiscal and/or monetary stimulus over the coming months. The promise to eliminate the deficit by 2020, the bedrock of the Osborne/Cameron years, was quietly discarded on a cold and rainy weekday when most lobby journalists were only capable of asking – or tweeting – whether Labour’s leader would resign. The biggest story since Brexit? That the raison d’etre of Cameron’s two governments was effectively bullshit. Not that you would know it from reading the dailies. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. Credit: Jonathan Brady / PA Wire/Press Association Images. All rights reserved.

The economic debate has moved with impressive speed. Theresa May will have to significantly break Osborne’s budget forecasts to implement an industrial strategy worthy of the name. That reality is why Owen Smith recently included a £200 billion stimulus as part of his leadership offer, something utterly unthinkable to Corbyn’s rivals last summer – and almost certainly Smith himself.

So the politics has changed, and it’s clear that with deficit elimination gone, and deficit reduction of little importance, Corbyn’s politics – interventionist, radical, socialist – have a real opportunity to challenge the mainstream. It’s probably unsurprising, then, that the criticisms now levelled against him aren’t about his policies – their time has almost certainly come – but his competence.

Now let’s be fair to Corbyn’s critics. The MP for Islington North is not ‘slick’ (although he appears all the more resilient for it). What is more, he certainly never viewed himself before last summer as a potential Labour leader. It’s no surprise, therefore, that the team assembled less than a year ago initially struggled, although it has improved tremendously in recent months. The Labour left simply didn’t have the resources or pool of experienced people on which to draw to prepare for potential government. After all, their function in the party was more ornamental than real for the best part of three decades.

Big mistakes were also made in regard to the shadow cabinet, foremost among them trying to include MPs who wanted Corbyn to fail from the very beginning, something few leaders would survive. More than incompetence, Corbyn’s original sin was generosity. Lisa Nandy, a standard bearer of the parliamentary party’s ‘soft left’, recently spoke of how the right and the left of the party were at war with one another. That simply isn’t true, at least not at the beginning. From day one Corbyn tried to assemble a broad cabinet. His reward? Political inertia, punishment, and almost ritualised humiliation, of which the ‘Chicken coup’ is only the most recent chapter.

In addition to various problems of personnel, ill-preparation and misplaced kindness, politics at the top is always a messy affair. The decade of the Blair-Brown supremacy was marked by ceaseless conflict within Labour’s front ranks. You only need to read anything by Andrew Rawnsley to know as much. The same was true in the final Thatcher years and nearly all of John Major’s premiership. Despite the easy ride he got from the British media, David Cameron’s position during the Andy Coulson revelations was more fragile than seemed apparent. In retrospect what made the coalition all the more stable was that the constant sniping – a perennial feature of statecraft – could be put down to two parties having to govern together. Just a year after he delivered the Tories their first majority since 1992, a historic achievement, David Cameron resigned – his legacy as poor as any of his predecessors since the Second World War. He would almost certainly still inhabit Number Ten had there been a second coalition government.

So politics at the top is cut-throat. All the more so in an age of social media. All the more so when many of your own colleagues want you to fail from the start. All the more so when the mainstream media treats you with a contempt, from the off, that has been reserved for no other politician in modern Britain. That, taken with the fact that the radical left was far from prepared to seize the initiative, and Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership looks all the more impressive.

What is more, and it is important to remember this, Corbyn does have considerable victories to his name including by-election wins, a massively growing membership (Labour are now bigger than at any point since the Second World War), and major u-turns from the government – particularly around welfare reform. More than all those however, which were accompanied by middling election results in May, Corbyn’s ten months as leader has significantly framed the space that Theresa May’s government is about to step into. The Overton Window has moved. The question is how far it is yet to go.

The devil is in the details

Yet it’s also clear that there is much that Corbyn can personally improve on. Self-improvement gurus often say that the solution to a big problem is the smallest tweak consistently applied over time. Similarly, the attitude of England’s rugby union team in the early 2000s was improving one hundred things by one percent. Constantly. In regard to issues of competency and daily media management that is my view with Corbyn: what is needed is an attitude of constant iterative improvement. The leadership is most certainly improving, and the team around Corbyn is now much stronger than before. Is there a desire for this? After the last month I really believe there is.

But as important as the belief that Corbyn is improving – and that issues of media management can be further rectified – his potential challengers have shown themselves to be utterly shambolic in the last few weeks. Even their supporters, in their heart of hearts, can’t think they have the answers.

The genesis of what became the Chicken Coup was devious, manipulative and short-sighted. Corbyn’s foes wanted him to resign without standing a challenger; then they wanted to keep him off the ballot altogether; then the rules for those able to vote were, quite frankly, gerry-mandered (that didn’t stop nearly 185,000 joining as registered supporters). Angela Eagle, originally put up to run by the likes of Hilary Benn (much of Eagle’s campaign team were ex-Benn staffers) pulled out last Tuesday to give Owen Smith a free run. Her actions have angered her local party in Wallasey who, having passed a motion of confidence in Jeremy Corbyn a few weeks ago, have now been suspended. It seems likely they would have passed a motion of no confidence in Eagle.

Before its timely expiration, Eagle’s candidacy was an exercise in farce. Its poor launch was preceded by two weeks of collective dithering – calling on Corbyn to resign while failing to make the next move. When the launch did finally happen, the essentials were lacking. The defining moment for that came when Eagle invited specific journalists to ask questions of her who weren’t even present in the room. For a candidate criticising Corbyn’s competence it was calamitous to watch.

What is more, Eagle – originally intended as a unity candidate by the right of the party who initiated the coup – was a politically strange choice. She had voted for war in Iraq and against an investigation, doubly problematic given events kicked off a fortnight before the release of the Chilcot Report. In terms of her position and voting record on austerity, Eagle was no different to the rivals Corbyn had stunningly defeated the previous summer.

So when the former cabinet minister stood aside on Tuesday, former Pfizer lobbyist Owen Smith became the last hope for those who wanted a new leader. And yet, as with Eagle, basic issues were obvious from the off. Smith, who has seemingly found a vein of political radicalism in his soul after five years of lobbying in the pharmaceutical industry, has clearly moved left to appeal to a very different party membership to even a few years ago. Nevertheless, his views on PFI, privatisation in the NHS and, only last year, reducing welfare spending, is plainly at odds with what the membership wants. Smith – we now know – is also prone to gaffes, making two major ones in the first few days of his leadership bid.

Social Democracy is in crisis: Owen Smith is no answer

But more than the individual flaws of any specific candidate, what is most concerning with Smith (who is now trying to pitch himself as a more electable left-winger) is that the politics he champions, and the direction he would like to take the party in – along with the likes of Ed Miliband – has no winning model in Europe. Centre-left politics – across the continent – is mired in defeat and inertia. Whether it be the SDP polling at 25% in Germany, the PSOE winning 22% in the recent Spanish General Election, or French president Francois Hollande polling at 13%, there are no real bright spots. The only arguable exception is Italy’s Partito Democratico, led by Matteo Renzi. Yet even there Renzi is PM having never contested a general election, and his predecessor but one – Pierluigi Bersani – led the Democrats to only 27% in the 2013 election (the coalition they headed won just under 30%). Last month the 5 Star Movement’s Virginia Raggi won the Rome mayoralty from the PD. Even with Europe’s best performing party of the centre-left, the story is one of managed decline.

The crisis of social democracy has been a topic of conversation for years. That has been turbo-charged by the fact that the centre-right has benefitted most from the global financial crisis of 2008. Ed Miliband and Labour’s electoral defeat in 2015 was testimony to that, with Labour winning only 9.3 million votes. Perhaps most concerning however, was how Labour lost votes to both their left, and their right. Were Owen Smith to be Labour leader for the next general election I think he would struggle to even get Miliband numbers: Greens would be less likely to switch to Labour, his vague offer of a second referendum on EU membership would almost certainly land UKIP a number of Labour seats in the north, and the Lib Dems, probably regardless of who leads the two major parties, will make a minor comeback.

Labour’s problems reflect those of both the British establishment and European social democracy, and to my mind Owen Smith isn’t a solution (nor indeed is any individual). While you can point to Corbyn’s low personal approval ratings – for what it’s worth I think any politician’s would be as bad given what he has uniquely faced – the Labour party he wants, and more importantly the one now under construction, arguably does. You see it’s not just about Corbyn, it’s about a party of a million members, grassroots organising and a generational break with a broken centre-left politics adrift across the continent. Labour now needs to invent its future. It has no choice.

Understanding Labour’s long decline

The obstacles Jeremy Corbyn will now have to surmount in order to become prime minister and oversee precisely that are unprecedented. Some of the parliamentary party will simply refuse to work with him if he wins again. Tom Watson will likely resign as deputy leader after any second Corbyn victory to exert maximum dramatic effect. Senior Labour MPs are seriously talking about annual leadership elections until Corbyn goes. On the bright side any split, which should be avoided at all costs, would likely only include the right of the party – led by the Blairite MPs named and shamed by John Prescott in a recent Sunday Mirror. Most, however, understand that any new party of the centre would face a very inhospitable set of circumstances: the historic social base of the SDP, progressives in metropolitan areas, are now a hotbed of Corbyn support. What is more, there are few examples of successful centrist projects worldwide right now – with the exception of Justin Trudeau’s Liberals in Canada. What is more, the Labour right clearly lacks a politician of that calibre. If they did, she or he would be standing against Corbyn, not Owen Smith.

In addition to the hostility Corbyn Mk. 2 will now face from many of his own MPs, and as many MPs on the soft-left need to be won round in the next few months as possible, the Labour party machine is nowhere near good enough to win a general election. That is true at both local and national levels. Half-a-dozen people have described to me how the party HQ is set up to win an election in 2005 rather than 2020, with problems going a long way back. After all, before Corbyn’s rise last summer, the party hadn’t won a general election since 2005. Even then it lost forty-six seats to Michael Howard’s Tories. Indeed Labour has lost seats at every single general election since 1997, almost two decades ago.

In terms of actual votes, Labour lost five million between 1997 and 2010. Ed Miliband’s brand of heavily triangulated, frequently contradicting soft-left politics won back fewer than a million of them last year. For my money that is the ceiling on the party’s vote with his brand of politics and its present organising structure. In other words, Owen Smith.

Looking back, the rise of Blair – and his historic election win in 1997 – was as much one of Tory decimation as Labour ascendancy. The mid-1990s were a unique cycle in global capitalism since the early 1970s, with GDP, employment and real wages all rising. The factors behind that – the doubling of the global labour market foremost among them – aren’t going to be repeated again. But alongside the bigger economic picture, the Tories were also in chaos. Winning the 1992 General Election was the worst thing that ever happened to them. Within twelve months the party needed the votes of Ulster Unionists to pass legislation, and Major’s second term was permanently furnished in crisis. No Labour leader, before, since or likely ever again, will be offered that kind of opportunity. The dynamics behind 1997, as much about Tory collapse as Labour supremacy, effectively carried on for a decade, with Labour’s vote steadily decreasing but the Tories incapable of taking advantage. Thus even at its zenith, the Labour machine was a never particularly impressive one. Those on the Labour right who talk of imitating the US Democrats have shown neither the skill nor foresight over the last two decades to come good on their lofty ambitions. Given they have controlled much of the party’s formal infrastructure during that period, especially at Victoria Street, it’s fair to say it isn’t going to happen.

A different kind of leadership; a member-based party

Jeremy Corbyn is not a generic political leader. But perhaps that doesn’t matter as much as some think. Twenty-First Century leadership takes many forms with it not only being about attracting supporters – but more importantly – creating more leaders too.

While he will never look like a Hollywood impersonation of a PM, what Corbyn can do – and is doing – is give rise to a movement. As Paul Mason says, he is a placeholder. That phrase needs to be more than rhetoric however, it must inform an organising strategy by which Labour comes to have more than a million members and can feasibly form a government after the next general election.

But before explaining how that happens, it’s important to clarify why Labour’s growing membership is such a game changer. Well, the Conservative party dominated British politics for much of the 20th Century because they had significant resources that others did not: three million members (yes, really); influence among opinion-makers and the mainstream media; and wealthy supporters. Labour’s greatest hour came in 1945 when, to the astonishment of many, Winston Churchill was replaced by Clement Atlee. The basis of that was a popular movement, a uniquely changed political context and a vision for a different kind of country. Labour only wins as a movement.

As I hope to have made clear, the major exception to that – 1997-2005 – was as much a story of Tory decline as Labour success. What is more, that project was in decline almost immediately after its high point. The Conservative leaders of the early 21st Century, William Hague and Iain Duncan-Smith, even Michael Howard, were at the time harder to imagine as prime minister than Jeremy Corbyn is now. That was without kamikaze elements within their own party and the collective force of the entire mainstream media arrayed against them.

So if the Tories (almost always) win because they have more money and media influence – the members have long since gone – what does Labour have? During Labour’s great exception at the end of the twentieth century, the view was they had to ‘spin’ better than the Tories while converging with them in key policy areas, particularly wages, housing and industrial policy (i.e. not having one). That led, in the long-term, to the decline I’ve already identified: the party’s working class heartland being taken for granted to win swing voters in marginals elsewhere. That strategy is now a busted flush, not least because Scotland has now gone and those industrial and former mining areas no longer look quite so impregnable. Over the same period the party neglected member-based democracy, local organisation and effective ground campaigning.

Rather than spin, or a hotline to Rebekah Brooks or Paul Dacre, the biggest resource the Labour party can now possibly have is its membership. That membership can, potentially, serve to do several things. Firstly, it provides the party with a much sturdier financial base (the party, rather than rely on wealthy backers, would have been long bankrupt without affiliated trade unions and loans); it creates a large base of advocates who can informally persuade their own social networks and formally campaign among strangers; and, with social media, it creates a huge network for the self-broadcasting of Labour’s ideas, policies and events. None of this is inevitable with the rise of a mass membership, and appropriate organisational choices have to be made, but it is a pre-condition for it. Again, I believe none of this happens with Owen Smith as leader.

My contribution here is this: among that million plus membership, the party will need 100,000 change advocates to make significant inroads. These are people who are trained to campaign in local areas as well as reaching out and getting even more people to join the party. While Momentum could oversee such an undertaking, it may well require a well-resourced and committed organisation, equivalent perhaps to the American New Organising Institute (albeit with adaptations for the British context). These 100,000 activists would be a major part in winning any ground campaign against the Tories and building even wider circles of local support on a constituency-by-constituency basis, starting in marginals. Were the future selection of parliamentary candidates to be undertaken through local primaries, something I inclined towards, registered supporters would also be able to participate.

The electorate should thus be seen as an ever larger set of concentric circles: at the heart are these change advocates, then members, then registered supporters, then Labour voters, then potential Labour voters. If organised properly this would be a very competitive force during elections. As much as persuading strangers, activists would be mobilising pre-existing affinity groups of friends, families and colleagues to not only vote for candidates, but campaign for them as well. Additionally they would interface with extant efforts around things like food banks as well as beginning initaitives like literacy groups and breakfast clubs. How would this be funded? The party would build something that integrated Act Blue and JustGiving to enable dis-intermediated financing of these projects by members as well as the general public. That Labour was able to raise £4.5 million in just 48 hours in the recent registration of supporters, is testimony to the good will and resources out there. Charitable giving in the United Kingdom is significant, that culture should be channeled within any modern mass-membership party that aims at systemic change.

As much as building the party membership, and crafting it into a force capable of persuading the general public and even engaging in social reproduction, any campaign that sees Jeremy Corbyn into Number 10 will have to exhibit features of a movement assemblage rather than a political party. That assemblage will engage in personalised campaign practices.

Now I know what you are thinking – an assemblage? Personalisation?

Until very recently general election campaigns have been hybrids of professionalised party efforts which incorporate large numbers of volunteers. The volunteer efforts were almost entirely for offline ‘ground’ campaigning, while professionalised elements included public relations, media and fundraising. That has dramatically changed in recent years through the emergence of social media and crowdfunding. Additionally, the last decade has seen a move to ‘personalised political communication’, especially in the United States. This kind of campaigning places an emphasis on ‘ground war’ practices such as door-to-door canvassing and phone banking, both pursued with the help of allied groups, volunteers, and paid part-time employees. This kind of communication is ‘personalised’ in the sense that people, and not television or websites, serve as the primary media for messages (Kleis Nielsen 2013). All of which means that media and mobilisation functions are now fusing into one another. In the English context, one saw this for the first time in Corbyn’s campaign last summer – especially in phonebanking efforts that deployed the ‘Canvassing’ app – the Corbyn campaign found scale through the personal media networks and efforts of tens of thousands of advocates – and how this interacted with legacy media – rather than simply the old ‘one-to-many’ channels. This explains, to a significant extent, how Corbyn can currently enjoy a 32% lead over Smith among the membership despite little to no support from the mainstream media.

Survey research demonstrates that tens of millions of citizens are contacted in person or by phone by parties and candidates each cycle in the US, and experimental research in political science suggests that it works (Kleis Nielsen 2013). Corbyn’s first campaign for Labour leader brought that model to the UK – and his second one will likely improve on it.

So the first aspect of Labour as a campaigning assemblage is to acknowledge this model of campaigning, its relative absence in the UK, its potential effectiveness, and use its large, growing membership accordingly. Again, I don’t think anyone believes this happens with Smith. Without such an approach, at least until Labour wins the wholesale backing of the print media and the financing of oligarchs, Labour simply have no other route to power.

But as well as channeling this new kind of personalised campaigning through an ever-larger membership, Labour also needs to embody both collective, and connective logics of action.

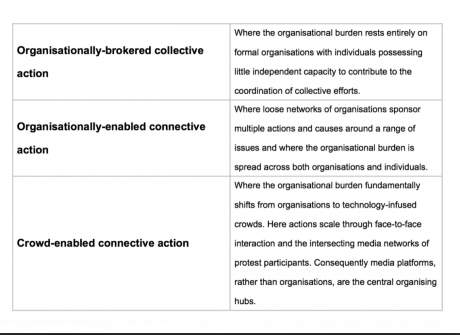

In their recent, groundbreaking work, Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg distinguish between the traditional logic of collective action that has been accepted within much of the social sciences for decades, and observably different logics of connective action which have recently emerged in the digital environment. As a result they offer a three-fold typology of large-scale action networks, with one representing the brokered networks characterised by the logic of collective action (Olson 1965) and the other two exhibiting the newer logics of connective action. These are as follows:

Traditionally most formal political efforts – from voter registration campaigns, to protests and elections – have relied on the first kind of action. That necessitated hierarchy, incentives for participants to not free-ride (often paid jobs or status) and a highly centralised operation. Fundamentally, it presumes higher costs for information than is, in reality, now the case. So while one might think of politics, until recently, as being about top-down, organisationally brokered collective action, it isn’t. In the recent referendum on membership of the European Union, the ‘Leave’ campaign more closely resembled organisationally-enabled connective action than ‘Remain’. We also saw it in the nomination campaigns of both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump in the United States. While Clinton, with a more classically vertical campaign did ultimately prevail, Sanders picked up an astonishing thirteen million votes. The reality is that in the contemporary media environment the choice isn’t between hierarchy and networks but between more collective or connective strategies. Both require organisation and leadership, just different kinds. Because of a relative lack of resources my view is that Labour can never compete through collective action strategies, hence the importance of the Corbyn project, member-based democracy and organisational renewal.

Bernie Sanders supporters, image: the Bernie Sanders campaign.

The major reason why Jeremy Corbyn won the Labour leadership so convincingly last year was because elements of all three logics were evident in his campaign. His triumph was powered by old-fashioned politics – such as winning trade union support – but also by a groundswell of grassroots support which managed to achieve tangible things: remote phonebanking, events organising, social media campaigning and, most importantly, getting new members to join. Much of how this was achieved was through crowd and organisationally-enabled connective action which fosters much higher levels of personalised communication. That was expedited through organisational forms, both formal and informal, that one would not typically associate with British electoral politics.

Had Corbyn’s campaign tried to win through old-school collective action they would have lost, quite simply because they lacked the resources - primarily money and media exposure - of the other candidates. Its important to remember that while Corbyn may be naturally open to this kind of approach, one where formal efforts easily interface with what feels like a social movement and an amorphous body of support, his campaign also had high incentives to adopt it, or at least be comfortable with it.

Sadly, once Corbyn did win, that approach was dispensed with. There was the general presumption, ultimately misguided, that such efforts could be easily channeled into the Labour party. But modern action – at its most powerful – doesn’t work like that. For Corbyn’s Labour to be highly competitive there needs to be the recognition that both collective and connective action logics are necessary, and that these will be mobilised across a range of actors which enjoy distinct organisational features. That means a great deal of autonomy to local activists to organise with an emphasis on personalised communication; strong levels of access to media that is beyond the mainstream; content created by Labour, Corbyn’s office and others that is not aimed at their supporters but is, instead, intended to be re-broadcast by them; and a general approach that seeks to choreograph events rather than lead them. It requires more than simply telling supporters it is their movement, but to build things so they experience and produce it as their movement, daily.

Much of this may sound like new management speak, but these were the precise organisational dynamics which saw Corbyn win last summer, as documented by digital campaigner Ben Sellers. Such an approach will not only mean Labour exerts more media influence, but will also mean higher levels of mobilisation (such as door-knocking, leafletting and ‘get out the vote’ campaigns) and more resources (not only through membership subs but also crowdfunding efforts). Again, none of this seems to be on offer with an Owen Smith leadership. Jeremy Corbyn, perhaps surprisingly, appears to offer the only path to a Twenty-First Century party in Britain.

In the following months, in the knowledge that personalised communication, campaigning assemblages and connective as well as collective action are all integral to a successful Labour ‘machine’ (one that actually goes beyond the party) I would suggest that several things begin to happen.

Firstly there needs to be a discussion about the ecology which would exert media influence and mobilise activists. In regard to the former the leading channels the Corbyn leadership wants to operate through need to be identified, particularly with television (beyond current affairs shows) and new media. Additionally, influencers need to identified. I’m circumspect as to how much they can change minds – after all, David Beckham’s intervention on Brexit went down like a lead balloon – but they undoubtedly extend reach, especially with specific, targeted demographics. This is especially important in regard to the coalition of voters that Corbyn’s Labour must now build. In regard to mobilisation, I would imagine something equivalent to the NOI should be set up. It would offer not only training, skills and experience for 100,000 organisers, but certification too. These organisers would advocate the new politics, but also add new members. They would also be the basis by which party activists begin to engage in local community organising beyond electoralism. As mentioned, in terms of funding those projects the party needs its own equivalent of Act Blue to fund local campaigns and initiatives. The problem, with a national membership of over half-a-million, is not raising resources, but effectively channeling them to where they are most needed. If Labour HQ is too short-sighted to create these two institutions, others should. They will be crucial in the assemblage that makes Labour a serious electoral force.

Labour needs to identify and build its coalition of voters

Alongside creating the right ecology through which it can flourish as both a campaigning movement and electoral force, Labour needs to understand the coalition it must build to win. Again, I think that Corbyn – and more importantly the changed Labour party he will lead – offers much more promise here than Owen Smith.

While Labour must remain rooted in the trade union movement, one thing it can learn from the US Democratic party is how to build a social majority which beats ‘Middle England’. In both 2008 and 2012, Barack Obama won the White House despite being relatively unpopular with what is presented as the deciding force in politics: white men. While Britain does not have the same ethnic composition as the US, Jeremy Corbyn – or indeed any potential Labour prime minister – will have to do something pretty similar. Obama’s ‘coalition’ was women, the young, and BME voters. In terms of who joined Labour during and immediately after Corbyn’s campaign last summer, something similar happened with the party’s 150,000 new members, with joiners tending to be younger and female.

Labour actually won the last election among under-45s. A primary task for Corbyn, then, would be to generate a considerable increase in turnout among that demographic, as in fact happened in the recent referendum on membership of the European Union. This is low hanging fruit, and should be a central aspect of Labour’s electoral strategy.

In fact Labour needs a considerable increase in overall turnout just to stay where they are after boundary changes. Again, I don’t think Smith can do that. The difference between Al Gore in 2000 and Barack Obama in 2008 was a 7% increase in turnout for the latter. Labour now needs a similar trend in England and Wales just to stay competitive.

In addition to more people powering a higher turnout, particularly among the young, Labour also needs to win a majority among women and BME voters. Nowadays women are more likely to vote Labour then men – although in last year’s general election it appears almost certain that most women voted Tory. Labour did however have a big advantage among women under 50, enjoying a six-point lead. Along with increasing turnout among that vote – far more likely to vote Labour anyway – Corbyn also needs to win a majority of women next time round. Against a second woman as Tory prime minister – Theresa May – that would appear difficult, but anti-austerity policies, as well as big offers on pay discrimination, social housing and care (adult, child and for those with disabilities) would be very popular. As already mentioned, a national base of activists – mobilising around issues of social reproduction – would be a major difference here.

Corbyn’s Labour will also need to win the BME vote, something Labour historically does anyway. In 2015 Labour won 65% of BME votes, an increase of 5% on five years earlier. Again, as with younger voters the aim must be to get far more of this demographic to not only vote but to actively campaign for Labour. That will go hand-in-hand with Labour becoming an effective organisation for anti-racist activism in the years ahead – something crucially necessary given the growth of xenophobia and racist violence in the aftermath of Brexit. Can Smith do that? It’s unlikely given his comments on immigration in his recent Newsnight interview.

But along with Obama’s coalition, the big ask for Corbyn is how you win such a ‘social majority’ while maintaining the party’s historic heartlands in former mining and industrial areas. On a range of issues, from Europe to migration, such areas express diverging attitudes with Labour’s metropolitan core. If just this balancing act can be achieved, in the process seeing away the challenge of UKIP, Corbyn would enjoy a much more successful general election than Ed Miliband a year ago. With Owen Smith, given his lobbyist history, his offer of a second EU referendum and his pro-austerity policies, something similar seems unlikely. For me, Labour wins those areas, and handsomely, with a big offer on industrial strategy, jobs, housing and a new kind of economy. This will go hand-in-hand with critiquing a failing model of globalisation, but insisting the solutions are economic and around issues of labour reform, rather than immigration. There can be no doubt about it, this will take years, but it is absolutely crucial.

So in terms of who is more likely to win, or even compete, at a general election between Corbyn and Smith I would suggest Smith can’t build the necessary coalition that Corbyn can. Yes, Smith might look a lot more appetising to southern swing voters, but when you zoom out, that is less important than it looks.

What is more, Corbyn offers Labour a path to reinvention. The centre-left is dying across Europe, and I’d suggest Owen Smith would take Labour in a similar direction. Can Corbyn become the next prime minister? It’s possible, but it depends both on the growing movement that now surrounds him and how his leadership interacts with it. Most importantly, his leadership can feasibly change Labour, at both a local and national level, into a party fit for the modern era. As important as winning elections and modernising the Labour party, is how a mass, active membership can not only re-define party politics, but Britain. We need change in Westminster but also across civil society. Only Corbyn offers that.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.