Books & Culture

Curating a New Literary Canon

Who (and what) deserves to be in America’s first museum dedicated to writers?

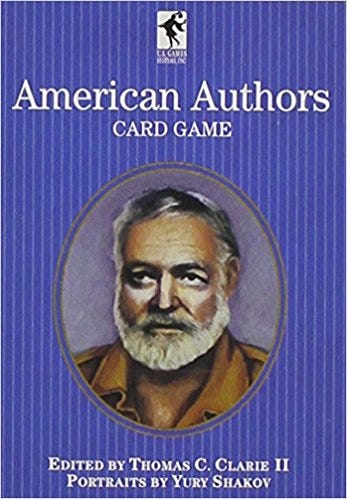

The Christmas I was eleven, I received, in my stocking, the 1988 edition of the American Authors Card Game. An update of the classic Game of Authors deck first introduced in 1861, it featured thirteen authors, one for each number (Robert Frost, for instance, was on the 5’s), each card showcasing a different work by that author. It was for this reason that two decades before I read Moby-Dick, I could have told you, with great confidence but no real understanding, that Herman Melville also wrote Billy Budd and Omoo and Typee.

The original 1861 edition included twelve white men and one white woman (Louisa Mae Alcott). My 1988 deck featured… one woman. This time it was Willa Cather, and she was, naturally, the queen. James Baldwin had joined the fray, but the remaining eleven authors were white and male. Being a kid, I thought nothing of this. I just figured Theodore Dreiser was someone important enough that any well-educated child ought to be able to rattle off four of his book titles.

Cut to ten years later, when I nearly broke up with a college boyfriend because he refused to acknowledge the ways canonization was wrapped up in cultural hegemony, a word I’d only learned within the previous six months. By twenty-one, this was a topic I’d passionately emote over when drunk.

Walking through Chicago’s new American Writers Museum a week before it opened to the public, I felt like a cross between that eleven-year-old (wide-eyed, thirstily trying to absorb the canon, inspired by history) and that twenty-one-year-old (tallying up gender and race and queerness on the 100-author “American Voices” wall of fame and doing some quick math).

The museum’s creators faced an impossible task, the same one undertaken perennially by anthologists and English professors: How can we represent four hundred years of American literary history in a way that doesn’t reinforce the unfortunate hierarchies of those four hundred years?

How can we represent four hundred years of American literary history in a way that doesn’t reinforce the unfortunate hierarchies of those four hundred years?

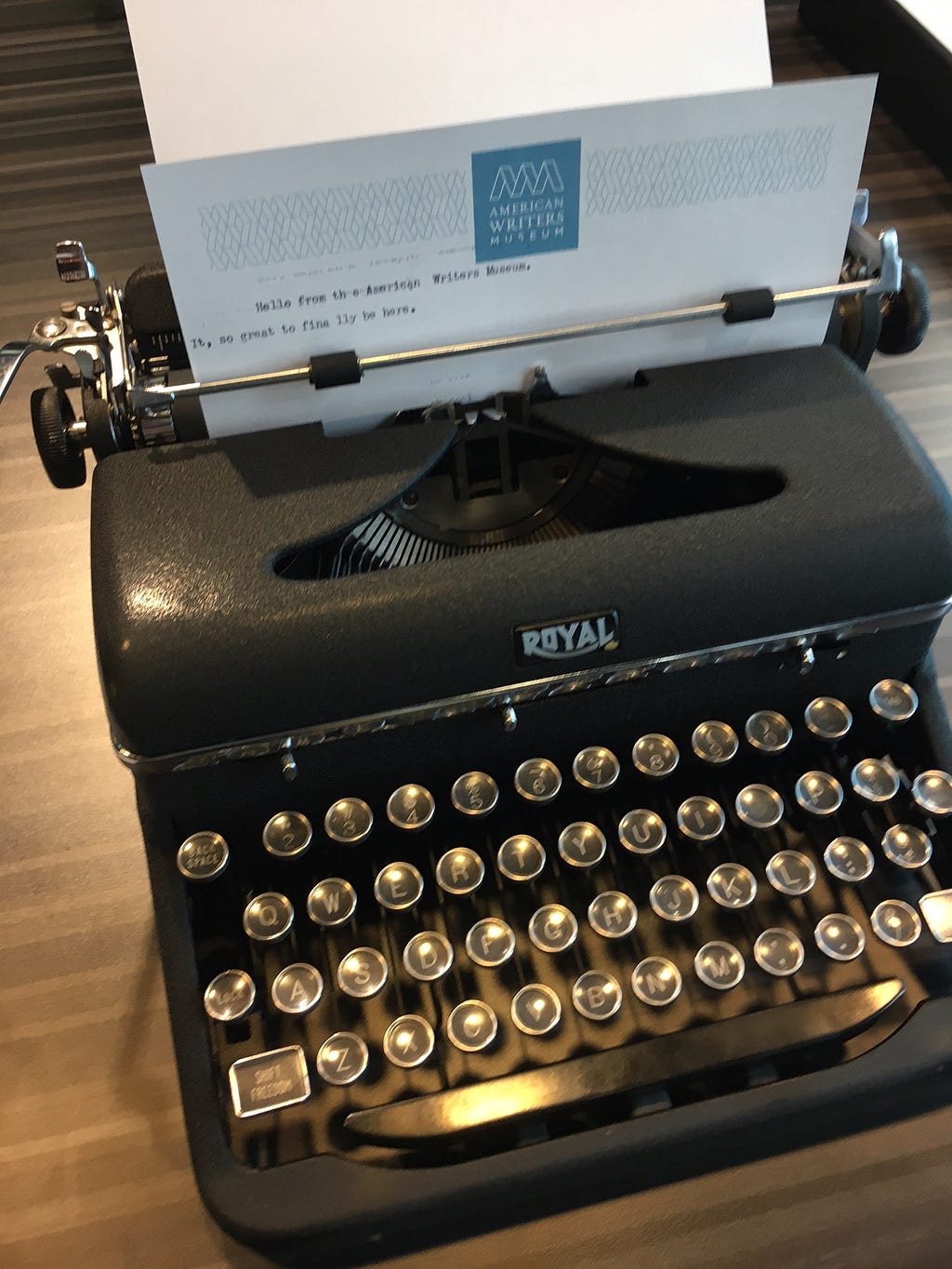

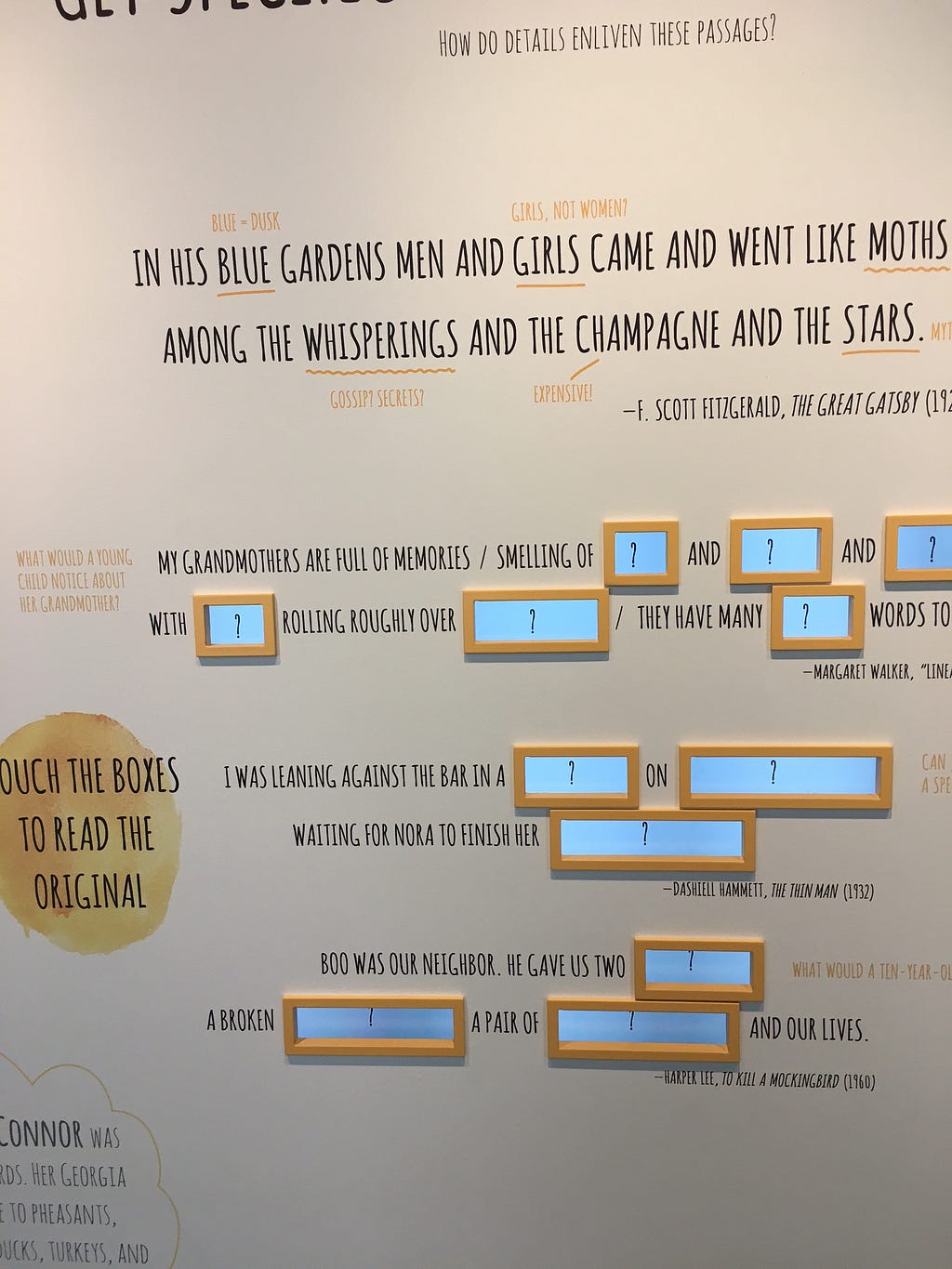

The museum itself, the only one of its kind in the country, is slick and sleek and exponentially more entertaining than you’d ever imagine a museum about people who sit in chairs all day could be. The second-floor space at 180 N. Michigan Ave. is appropriately lofty and quiet and gorgeous, with gallery spaces by Amaze Designs of Boston. Interactive games let users create poetry or compete to guess quotations or choose a quirky writing routine. Across from the author wall is a “Surprise Bookshelf” from which 100 small panels, each with the title of a different book or poem or song or movie, open to reveal photos, or play audio or video recordings, or (who can resist?) pump out scents. Elsewhere, there’s a hypnotic word waterfall in which quotes about America (not sappy ones, either!) reveal themselves in succession. You can take a Philip K. Dick-inspired test to figure out if you’re an android. Lest we get too modern, a charming bank of manual typewriters invites visitors to compose their own texts. A bit less charmingly, two kiosks let readers input data on their favorite books — data which is then mined not only by the museum but also by Goodreads (aka Amazon), who have loaned the museum the platform. (On the other hand, Amazon already knows when you’re out of toilet paper, so perhaps this is a benign violation.)

One of two temporary exhibits features the scroll on which Jack Kerouac feverishly wrote the original draft of On the Road. (Inspiring takeaway for visiting 11th graders: write high!) While I’m not a Kerouac fan, this is the kind of stuff that gets me: actual artifacts that real writers touched. I learned more about writing from studying a marked-up reading copy of one of Charles Dickens’ stories at the Dickens House Museum in London than I did from several writing workshops combined. In Sewanee, Tennessee, I once stared in awe for ten full minutes at Tennessee Williams’ toaster. His actual toaster! That he put his bread in every morning! My wish that the museum could include more objects like these might be selfish, but I don’t think I’m alone. Perhaps it would be too costly to acquire Hemingway’s fishing rod, but I can’t imagine Amy Tan would begrudge them the loan of an old mouse pad.

Perhaps it would be too costly to acquire Hemingway’s fishing rod, but I can’t imagine Amy Tan would begrudge them the loan of an old mouse pad.

I found the other temporary exhibit deeply confusing. You walk into a dimly-lit greenhouse-inspired space and make your way through some potted palms to listen to poems by W. S. Merwin, Ross Gay, and others. It has something to do with Merwin living in Hawaii and taking care of plants, and is meant to be an experience — one that’s never adequately explained. By the time I’d been whacked in the arms by three sharp palm fronds and stared in confusion at the ambient props — rubber boots, a roll of duct tape — I wasn’t as receptive a poetry absorber as I might have been. Was this Merwin’s actual duct tape, on loan? (If so, I take it all back.) Making one exhibit space educational and the other experiential is, though, a grand idea, and I have great hopes that in the future I’ll be able to walk through Richard Wright’s Chicago or lick Roald Dahl’s wallpaper.

Dungeons & Dragons & Communal Storytelling

I was involved in two different fundraisers for the museum during its seven-year planning phase, and although I lent my support to it as wholeheartedly as I’ll support anything literary in Chicago, I wasn’t the only one a bit baffled, early on, as to what this space was intended to be. “It’s not going to be a library,” we kept hearing, and then we’d be shown a picture of some shadowy figures looking at some shadowy banners. What’s emerged from all that vagueness is in fact specific, beautifully designed, and engaging — a place that, confusing palm room not withstanding, will easily absorb you for an afternoon. It’s a fitting addition to Chicago’s already spoiled-for-riches museum scene, and, as poet Anna Castillo put it during a talk the day I visited, it’s “a reminder that we [as Americans] are a literary people.”

It’s a fitting addition to Chicago’s already spoiled-for-riches museum scene, and, as poet Anna Castillo put it during a talk the day I visited, it’s “a reminder that we [as Americans] are a literary people.”

I’m left not wondering what it is anymore, but, on the simplest levels, who it’s for.

A younger child could enjoy a few parts of it — the children’s literature room (in which one panel describes E. B. White as a “20th century Thoreau” — a point on which my own kids, sorry to say, would be lost), and some of the interactive games — but given the adult bent of most of the literature on display, and given that a woman of average height had to ask me to open some of the top Surprise Library panels for her, on the whole it’s not designed for kids. (If your kid is an exceptionally tall Merwin fan, rest assured she’ll have a blast.)

Adults, on the other hand, are going to fall into two categories: those who already know this stuff, and those who don’t care. If you already know Edward Said’s Orientalism, and you open a panel to learn that he “transformed the study of cultural exchange and power,” which you probably also already knew, you’re going to be less than awed. If you’ve never heard of Farenheit 451, opening a panel to see a video of a burning book might not do much for you. The museum does contain an event hall, though, and the calendar of upcoming readings promises to bring a steady flow of literary adults through the space; my wildest dreams see this museum paralleling, for fiction, the superb programming that the Poetry Foundation has already brought to Chicago.

I believe the sweet spot for visitors is adolescence. The eighth-grader who wants to be a writer and will absorb whatever you tell her about who’s important and why. The sophomore English class with the energetic teacher who gets everyone to pick an author off the wall to present about for three minutes. The college Lit major who drags his girlfriend there to impress her (and himself) with how much he knows.

In other words: Eleven-year-old me would have eaten this place up. I’d have played the digital magnetic poetry game and typed on the typewriters and taken mental notes on the writers I didn’t know yet, long before I was capable of reading their work. Fifteen-year-old me would have gotten all emo over the recordings of Langston Hughes reading his own work.

Fifteen-year-old me would have gotten all emo over the recordings of Langston Hughes reading his own work.

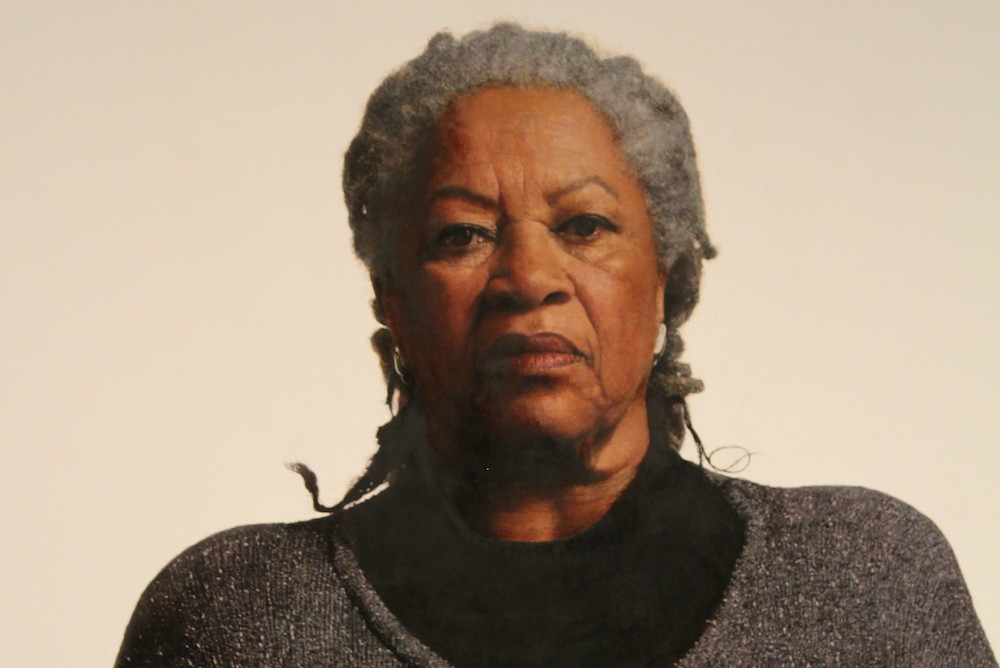

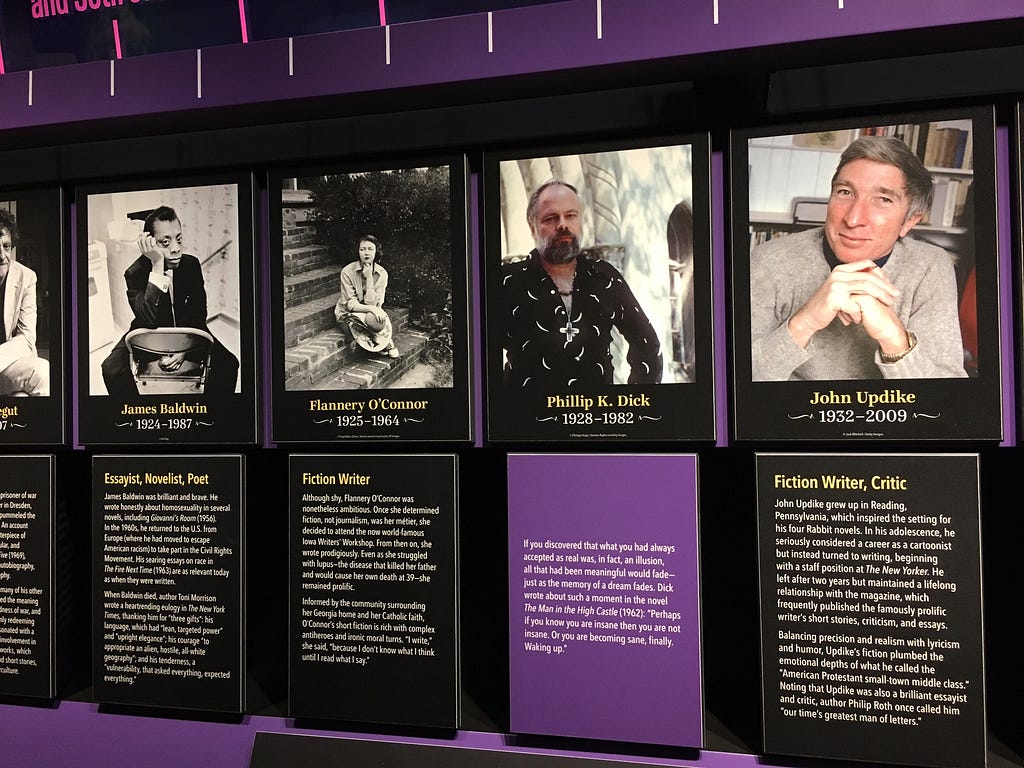

Meanwhile, twenty-one-year-old me would have freaked the hell out over representation. Because here’s the thing: Of the 100 plaques on the author wall, only 28 are women. 18 are people of color. Granted, we’re dealing with centuries of history in which women and people of color were not necessarily granted literacy, let alone publication. Poor Phyllis Wheatley can only hold up so much sky.

The ratios are far better than those of my 1988 card game, but in an exhibit for which the only rule is that the authors be American and deceased, there are missed opportunities. The writers on that wall are presented chronologically, by year of birth — Oscar Hijuelos, born in 1951, is the last — and of the last ten authors on the wall, only one (Flannery O’Connor) is a woman. That proportion might have made sense for the 18th century — but for the more recent past, what gives? Why not Adrienne Rich? Why not Lucille Clifton?

That said, there are serious efforts toward inclusion — of genre and populism and style, as well as race and ethnicity. Hijuelos is preceded at the end by August Wilson and, before him, by the Native American writers Vine Deloria Jr. and James Welch.

And it’s hard to point to the authors who should go. Would I really argue that Kurt Vonnegut should be dropped in favor of Lorraine Hansberry? Well, maybe. Yes, actually.

It depends, again, who this space is for. If the idea is to curate — to present to the world, in some official capacity, the Most Important People in American Literary History — then the battle is unwinnable. There’s no way we’re all ever going to agree. We see certain writers as canonical because we were always told they were canonical. That old question: If you’d never heard of the Mona Lisa, would you truly pick it out of all the paintings in the Louvre to stand in front of and gawk at? It’s famous because it’s great, sure, but there are other great things in the Louvre. It’s mostly famous because it’s famous; canonization is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If the idea is to curate — to present to the world, in some official capacity, the Most Important People in American Literary History — then the battle is unwinnable.

If, on the other hand, the idea of this museum is — as it seems to be — to inspire the next generation of writers, then why cling to someone like John Updike to the exclusion of, say, a single Asian-American author?

Of course it’s only the one wall that I’m harping on, and although I didn’t run the numbers, it’s possible that other portions of the museum do a better overall job with representation. (NB: Writers beyond the one hundred on the main wall are represented in the museum’s other exhibits and games; Asian-American authors are featured in the Surprise Library, for instance.) I don’t know that anyone could have done better than this at striking a balance between education and inspiration. But that wall is central, the first thing many visitors will see, and its very presence feels authoritative, definitive.

Ultimately, I’m thrilled that the museum is here — and you should be too — even as we should keep pushing and questioning what it is and what it’s saying. Just as we already do with anthologies — and just as the art world has been doing in regards to museum and gallery representation for decades. This space is, like American literature itself, a place to revel in and balk at and demand more from.

When my daughters are old enough, I’ll take them there and let them experience the unadulterated joy that comes with feeling you’re getting the important stuff, the quick download of all the culture you’ll need.

And then ten years later I’ll take them there again, and we’ll really talk.