Lebanon’s Judiciary: The Great Disillusionment

Lebanon’s judges are disillusioned, and the consequences of this disillusionment are concerning for all of us. While some judges may individually experience bouts of disillusionment, like any other person, its prevalence among them today makes the issue a distinctly occupational and structural one that goes beyond the feelings and condition of each individual judge. Our fieldwork clearly shows that the state of the judicial profession itself has today become a significant burden eroding judges’ morale and their connection to their profession and to justice in general. This change undoubtedly demands attention and is a cause for concern, both in terms of the nature of the phenomenon itself and its significance within modern judicial history, and in terms of its grave effects on judicial work today and in the coming years.

A Rare and Dangerous Phenomenon

Firstly, this collective disillusionment appears to be an exception in the history of the judicial profession in Lebanon, which was for many decades a source of pride for most of its members for various reasons. It was one of the most desired careers in Lebanese society. People long considered the judiciary to be a majestic career path in the public service. For many of them, the latter constituted one of the most important means of upward social mobility. Being a judge was a source of social pride and authority, as evidenced by the celebrations that would occur in villages and neighborhoods when one of their sons or daughters succeeded in the judiciary’s competitive entry exam. Such practices associated the profession in the minds of its practitioners with a great positive feeling, albeit not always for the right reasons. Several years ago, this feeling turned on its head, as we will see below. Occupying a judicial position has become a source of great anxiety and dissatisfaction.

Secondly, this disillusionment undoubtedly has grave consequences. It does harm to judges’ self-image and view of their social role, which negatively affects the judicial function that they currently perform both in terms of their interest in their work and people’s affairs and in terms of productivity (as we shall see in a later article). It also has consequences for the judiciary’s relationship with society. As this feeling has been readily apparent to the public, most people now view Lebanon’s judges in a manner that does not inspire trust in the judicial institution and its ability to guarantee their rights or hold the political authority accountable. They see most judges as exhausted, desperate, and seeking to leave the profession whenever possible or resigned to a situation that they now hate. Judges convince youth and law students not to even consider joining the judicial cadre because of the difficulties and now-meaningless sacrifices that the profession entails.

A crisis of purpose is shaking the Lebanese judiciary and its judges: the purpose of the job, the meaning of what they were once told is a “mission”, and the purpose of going every day to a court in which nothing works to perform work that – whatever the volume – seems meager given the enormity and complexity of the crisis afflicting the country. While we will address the effects of this great judicial disillusionment in later articles, below we will describe it and show its numerous forms, features, and branching causes. This description, we hope, will help paint an accurate – albeit sad – picture of the judiciary amidst the crisis and potentially allow more effective topical or general treatments and solutions to be devised in the future.

Below, we show how this great judicial disillusionment is driven by a set of comparisons that judges have been making, morning and evening, for at least two or three years. Firstly, we document a comparison that judges make between the judiciary’s present and its past during previous decades as depicted by the pre-crisis memory. The second is a difficult comparison that they make between their current selves and their aspirations and dreams when they entered the profession. The third is one they make between themselves and other people working in other public and private institutions and other legal professions. Finally, there is the comparison between their capabilities and people’s expectations of them, especially under these difficult circumstances following the total collapse, the culprits of which they have not yet been able to hold accountable. All these comparisons intertwine today to form the recipe for this great disillusionment.

Nostalgia for a Better Past, Crushed by the Present

We found among judges an intense feeling that the profession has depreciated over time. In the view of many judges we met, the judiciary is no longer on the same level that it was before. The past for which judges long may be the pre-Civil War period, which they see as a golden age when, in the words of one judge, “the Lebanese Judiciary was a beacon of light in the entire region and other Arab countries were sending their judges to train beside trilingual Lebanese judges.”[1] The experiences of Antoun Saadeh and Judge Nasib Tarabay, however, show that this era was hardly perfect. It could also be the post-war period, when the judiciary was still teeming with figures renowned for their authoritative jurisprudence in law or ethics, or for standing up to the people in power.

“Notably, in the heyday of occupation and Syrian tutelage, Ghazi Kanaan and Rustum Ghazaleh did not dare do such things [that today’s politicians do inside the judiciary]… Of course, there was interference, pressure, imploring, and corruption, but they occurred in secret. Today, they occur openly and in an official manner. No prime minister or minister of interior dared to do what they do today. Even Rafic Hariri, who appropriated the whole downtown area, did not interfere in the judiciary in the flagrant manner that we see today when a prime minister asks the minister of interior not to implement judicial decisions.”[2]

Whatever the meaning of this hazy past may be, judges’ nostalgia for it and their disillusionment indicate a tremendous sense of institutional decline that has been ongoing for at least 20 years. However, the crisis significantly accelerated the decline and steered it in a disheartening and humiliating direction that even the most pessimistic judges could not have anticipated five years ago. This comparison of the judiciary’s present with its past also affects the public’s view of the institution, or so judges feel. Their excessive sensitivity to the way others see them is itself another symptom of this dark era.

Judges Look in the Mirror of the Crisis: Why Did I Enter the Judiciary?

The past that has rendered the present unbearable is not just the past of the judiciary as an institution but also each judge’s personal past. Many judges feel disappointed because their judicial careers have not lived up to the expectations, aspirations, and dreams they had when they entered the profession. In their view, the profession no longer provides the intellectual advancement, the psychological satisfaction, and – of course – the financial comfort to which they aspired. Their career advancement has usually not occurred at the pace they would like, and it has recently been largely paralyzed, especially as the entire personnel charts have been plunged into the quagmire of political and sectarian quota-sharing.

“I don’t feel like I’ve really spent 20 years in the judiciary in terms of career advancement. In 20 years, I’ve witnessed just two personnel charts.”[3]

To the judges we interviewed, the judiciary has in recent years become nothing but a “waste of time and capacities”.[4] They entered the judiciary “to examine and rule on cases”[5] and ensure rights and freedom. But they have found themselves dealing with logistical problems all day and facing political and judicial interference in their work that they have no ability to curtail, however independent and honest they may be. How can an independent judge curb the enormous political interference in the personnel charts? How can an independent judge hold corrupt criminals accountable if the Public Prosecution or investigating judges do not perform their role in accordance with the law and public interest? What can independent advocates-general do when a case is withdrawn from them or the appellate or cassation public prosecutor takes control of it, given the crushing hierarchy of the Public Prosecution and concentration of prosecutorial powers in the hands of the politically appointed cassation public prosecutor? The multipronged structural control of political actors and their judicial representatives over judicial processes and procedures makes judges feel occupationally stifled and renders their individual independence – where it exists despite the current law’s weak protection of it – meaningless.

“I traveled abroad and saved myself a bit more than a year of time-wasting and mental torment.”[6]

This disillusionment has not always been dominant during the last few years. Rather, it was interrupted by moments of fleeting hope: the appointment of Judge Suhail Abboud as Supreme Judicial Council president in 2019, the election of Melhem Khalaf as Bar Association president, the street protests demanding an independent judiciary, and so on. However, when the disappointments came, they were especially severe because of all the futile hopes, as the judges explain. They realized that the most important things had not changed (or had changed for the worse) and that the things they were betting on would be ineffectual so long as the political and legal infrastructure for a sound judiciary does not exist.

“Why am I burying my potential somewhere I’m not forced to be? It’s nice for life to have challenges, but if your entire profession or life becomes a challenge, then what’s it all for? However much you work, in one fell swoop everything is gone. It’s become nothing but suicidal.”[7]

The Judiciary in Light of Other Sectors: Nobody Cares About Us

Judges do not compare themselves only with the judicial past and the career paths they had envisaged. Rather, they also look toward other professions and sectors, especially the public sector and the justice sector. To begin with, the other authorities, represented by the government and Parliament, appear to be thriving when the judges look toward them from the neglected offices in the courthouse, knowing the judiciary is suffering severely from the crisis.

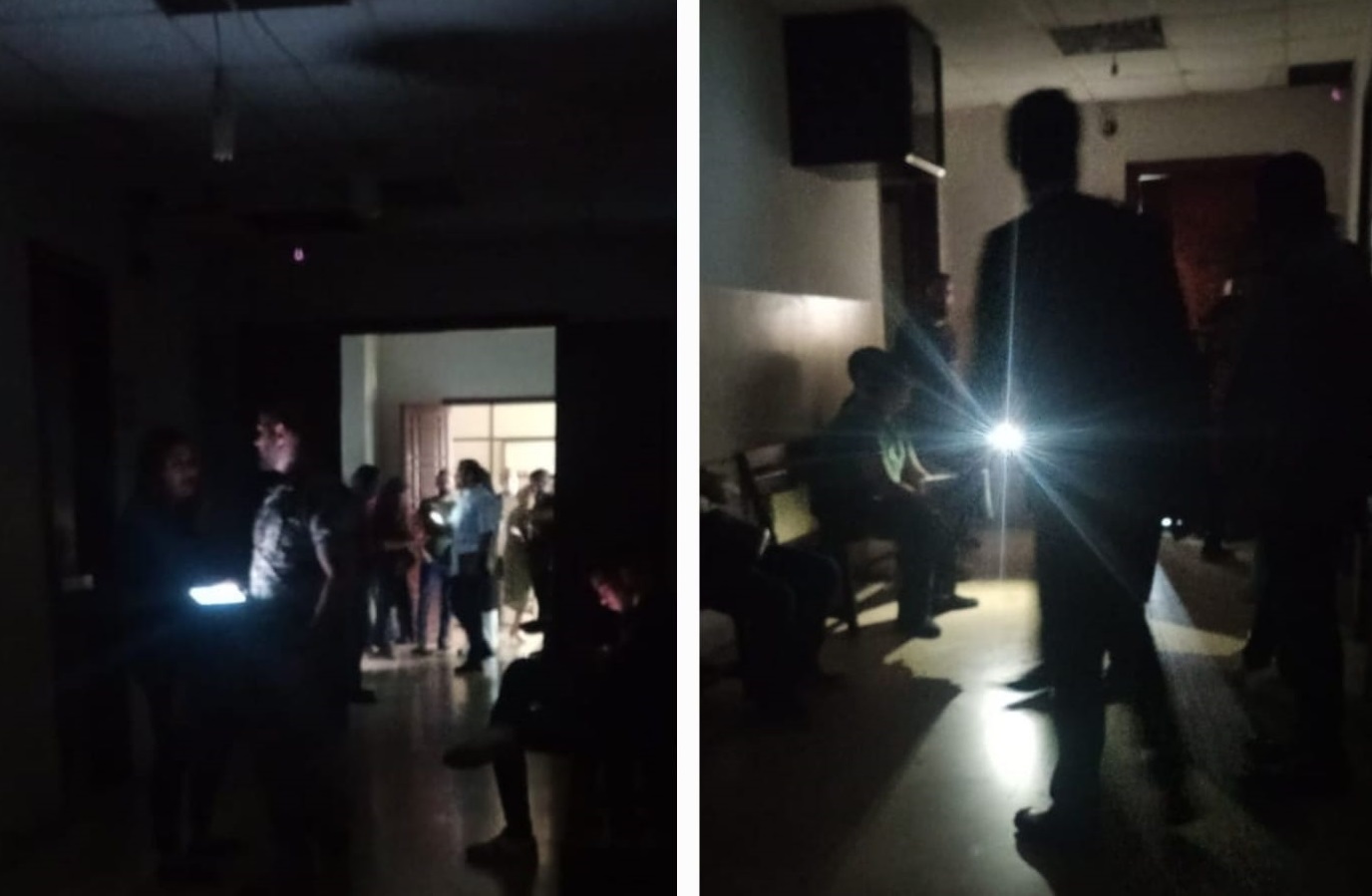

“I don’t understand why they are leaving the judiciary in this dire situation today while the government and Parliament receive all the funds to take care of their business. If you go into the bathrooms in Adlieh [the judicial district in Beirut], you will see their disgusting state. As for the government and Parliament’s bathrooms, they’re in better shape than the best of bathrooms”.[8]

Judges used to express this comparison as an aspiration to perform their role fully as a constitutional authority parallel to the legislative and executive authorities. Since the beginning of the crisis, however, they have expressed it through constant lament over the vast gap in social and political status that now separates the judiciary from these authorities. Judges complain that the other authorities do not treat the judiciary as an authority; rather, “they treat judges as though they are public servants”. Undoubtedly, the stark difference between the way judges see themselves and the way the other authorities and the people see them is another key source of their despair.

The comparison does not end there; rather, it also extends to public sector employees. When judges attempted to improve their circumstances a little via the “July mechanism” (whereby they tried to take their salaries at the exchange rate of LL8,000 to USD1 in July 2022), they were shocked that “every public servant of the first class stood against them because they were not included among the mechanism’s beneficiaries”.[9] The judges were dreaming of being treated like a president, prime minister, or Parliament speaker only to find that everyone insisted on treating them like all public sector employees. They were dreaming of full and respected constitutional authority, yet they were being treated like any state administration – or even worse than many of these administrations.

The hell of the numerous and constant comparisons continues. Judges compare themselves with Ogero employees and wonder whether the company is more important than the Lebanese judiciary: “Its employees managed to achieve their demands after two days on strike [in 2022], whereas judges stopped working for many months and nobody cared”.[10] They also compare themselves to the security agencies, complaining about the importance assigned to these agencies at the judiciary’s expense.

“The judiciary in Lebanon isn’t a priority. Lebanon is a security state. Aid comes to the security forces and then, later, everyone else. Law is something to deal with later. The important thing is maintaining security when something happens. The judiciary comes after”.[11]

Judges feel that someone is looking after all the security agencies, ensuring that their personnel have other material resources besides their salaries, but nobody is watching over the judiciary. They mention, for example, General Security and Customs, which provide their personnel with financial aid that enables them to secure additional monthly income. The judiciary has done no such thing, despite some ineffective attempts.

“My neighbor who works in Customs is a fourth-class public servant. His salary is many times higher than mine. He constantly asks me how I can live with my family on just LL6,000,000 per month (before the aid from the Cooperative Fund, when it operates). He can’t believe this. I tell him that I’ve gone back to being like a child who relies on financial assistance from his parents”.[12]

One judge explains to us how people accuse and complain about judges more than they do the politicians responsible for the situation. He says that “the security forces treat the judiciary with disdain” because they fiercely defend certain figures while “attaching little importance to defending judges or the courthouse”.[13] Is this judicial paranoia that has recently developed in the judges’ minds in parallel with their disillusionment and sense of neglect? Whatever the answer, this interpretation adopted by many judges depicts a harsh and gloomy world in which judges trust nobody, not even the people. Notably, lawyers confirm judges’ worst fears, describing to us how “the crisis has mellowed judges and reduced their arrogance” toward lawyers and litigants.[14] This suggests that judges’ nightmares may indeed be Lebanon’s new reality.

“In terms of morale, our situation is very bad. I have a big problem, to be honest. The way we look at ourselves… and judges’ sense of weakness before the security forces and politicians – you find that judges are trying to please officers. The security forces should serve the judiciary, rather the judiciary serving the security forces.”[15]

Judges Depressed by People’s Expectations

The greatest source of disillusionment among judges may be the Lebanese people’s expectations from the judiciary, especially those that it expressed during and after the autumn 2019 movement. Protesters expected the judiciary – or at least some judges – to play a pivotal role in holding political and financial officials responsible for the country’s collapse. However, judges did not meet these expectations for many political and structural reasons of which there is no room to discuss here. A climate of restlessness quickly returned to Adlieh, while disappointment befell spaces of popular protests. In this regard, judges might respond that they are even more disillusioned than the people, as they recognize their own inability to achieve any tangible results when it comes to holding anyone accountable, even if they have their justifications.

This sense of abject incapacity is pivotal. The Beirut port blast case seems to epitomize all other cases and plays a key role in the economy of incapacity, disillusionment, and despair dominating the judiciary. It “confirmed what was already certain”, namely that “the essence of power in Lebanon is the nonaccountability of politicians, and the Lebanese judiciary was not designed to be capable of holding influential people accountable”.[16] “Till now I remain powerless. I want to do something and I can’t,” one judge tells us.[17] The fate of the investigation into this crime, along with all the threats, campaigns, and obstruction that prevented Judge Tarek Bitar from performing his work, constitutes a lesson that some judges repeat to one another: when a judge dares think about holding political or banking officials accountable for their actions and negligence, Adlieh in its entirety grinds to a halt. This case has become one about judges being collectively punished because some of them dared to challenge influential figures.

“You leave judges alone with nobody to protect them and then ask them to prosecute and imprison Nabih Berri and the likes of him?”[18]

Judicial work becomes quasi administrative or logistical work with no relation to the things that motivated judges to choose the profession. Merely ruling on cases involving minor crimes no longer gives any significant meaning to their profession and even makes some of them feel ashamed toward the people, especially amidst the current financial and social collapse caused by perennial criminal practices for which the judiciary has been unable to hold anyone accountable. Judges feel that society sees them in a negative light, ranging from disappointment in the best case to accusations in the worst case, and blame them for achieving nothing significant.

“There are judges who removed their judicial number plates from their cars because they don’t have the guts to move among the people.”[19]

The judicial number plate may be the best symbol of the change and decline of judges’ circumstances. For many years it was a symbol of their privileges that accompanied them anywhere they went in the streets, roads, and public spaces, distinguishing them from other citizens. Today, it has become a heavy stigma that some judges struggle to carry and wish to remove. Indeed, the mirror of the crisis is very harsh on judges’ morale.

“I felt alone, and we felt like we’d lost everything.”[20]

This great judicial disillusionment not only harms the quality and effectiveness of judicial work but also threatens the future of the entire profession. It undermines the profession’s ability to attract new personnel to form the kernel of a better judiciary in future, given the faltering of the present judiciary. The decline of the profession’s social and political value and the incapacity that now distinguishes it, as well the deterioration of the material conditions of the courts and judges and the collapse of their self-confidence and self-image, are all factors that have been accumulating for four years to create a judiciary that few wish to remain in and few want to enter. The members of the judicial authority – which already lost its spirit as an independent authority in post-war Lebanon – are now losing much of their professional spirit. Consequently, this authority is becoming a mere vocation, and one that is no longer enticing to many people. The reform projects will have no value if we cannot restore this spirit to the judicial structure. We need a new judiciary whose core priorities include improving accountability, applying the law to everyone, and protecting rights and freedoms in order to restore some faith in a justice that abandoned Lebanon and its judges quite some time ago.

This article is an edited translation from Arabic.

[1] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[2] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[3] Interview with a judge, April 2023.

[4] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[7] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[8] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[9] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[10] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[11] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[12] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[13] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[14] Interview with a judge, June 2023.

[15] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[16] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[17] Interview with a judge, February 2023.

[18] Interview with a judge, March 2023.

[19] Interview with a judge, June 2023.

[20] Ibid.