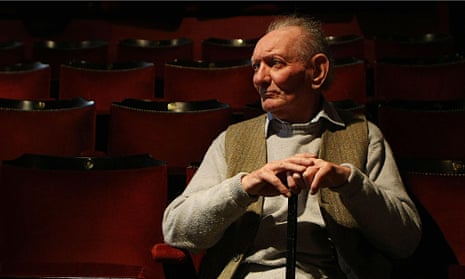

When asked why he had two birth certificates, one dated 9 January 1929 and the other 10 January, the Irish playwright Brian Friel, who has died aged 86, replied: “Perhaps I’m twins.” The reaction was typical of a writer acclaimed for the clarity, economy and intensity of his language and his probing of public and private anxieties. Living at various times on either side of the Irish border, he was preoccupied with aspects of dualism: divided loyalties, tensions between fathers and sons, the two languages and the island’s two political states.

He was propelled to international acclaim when Hilton Edwards’s 1964 Dublin production of Philadelphia, Here I Come! transferred two years later to Broadway. Subsequent successes in London and New York, including Aristocrats (1979), Translations (1980) and Dancing at Lughnasa (1990), established him as a towering figure on the stage. Other major successes, at home and abroad, included The Freedom of the City (1973) and Molly Sweeney (1994), the latter receiving a landmark production by Lev Dodin at the Maly theatre, St Petersburg, in 2000.

Friel nevertheless remained an intensely private person in the family home, increasingly reluctant to assume a public role. The Freedom of the City (premiered in Dublin and subsequently directed at the Royal Court by Albert Finney) was the only direct foray by Friel as a playwright into the world of politics. It was a reaction to the events of Bloody Sunday in 1972, when 13 civilians were shot dead by British soldiers during a civil rights march in Derry; a 14th died later; Friel himself was one of the marchers. The whitewash presented in the resulting Widgery report outraged nationalist opinion. Subsequently Friel was often criticised – mainly sotto voce – for his reluctance to write further plays on similar themes.

Translations excited controversy, in its portrayal of the English as efficient but ignorant, lacking the culture of the backward yet learned Irish peasantry. It had an immediate appeal to postcolonial audiences, and Friel joked: “Translations now playing in Estonia and Catalunya – American papers please copy.” In fact its success (the Times critic Irving Wardle called it “a national classic”) embarrassed Friel, and he wrote his only comedy, The Communication Cord (1982), as a sendup to prove that he was capable of cocking a snook at “traditional pieties” and the sometimes over-earnest search for Irish identity.

Friel’s dramatic fortunes rose and fell, principally because his work was uneven and unpredictable, but also because until 2005 there was no Irish equivalent of the British Council to promote Irish artists abroad. Translations had been a huge gamble, in theatrical terms, as was Wonderful Tennessee (1993), and whereas the former was a triumph, the latter was widely considered a flop, especially when it transferred to Broadway. Faith Healer (1979), arguably his greatest play, had failed on Broadway, despite direction by José Quintero with James Mason in the title role. American audiences could not take the total absence of action or even storyline. On the other hand, Molly Sweeney (similarly eloquent but lacking in action) succeeded in 1996, even though Friel had anticipated another flop, writing to me: “The NY attention span is now down to 2.7 minutes and the chances of holding an audience for 2.5 wordy hours in that city are slim.”

On the eve of Lughnasa’s transfer to Broadway, he sanguinely remarked to me: “It is a crude place where theatrical merchandise is bought and sold.” The play ran there for a year.

Born near Omagh, County Tyrone, in Northern Ireland, Brian was the son of Patrick, a schoolmaster and nationalist politician, and Mary Christina (nee McLoone), a postmistress. Friel remained close to his family roots all his life. Educated, like Seamus Heaney and John Hume, at St Columb’s college in Derry, Friel spent a trial period very unhappily as a clerical student at the National Seminary at Maynooth, before teacher training at St Joseph’s in Derry and a decade from 1950 as a teacher in various schools. Thereafter, the troubled authority figures of master and priest constantly recurred in his work.

Meanwhile, his mother’s home, the small market town of Glenties, in southern Donegal, across the border from Derry, was the origin of Ballybeg (in Irish meaning, literally, small town), the location of almost all his plays. Glenties was the hub of three international festivals of his work, in 1991, 2008 and 2015.

Friel’s international status was founded on the profoundly local: the universal resonance of Ballybeg, which projected him as “the Irish Chekhov”, emphasising his extraordinary affinity with the Russian playwright. Friel addressed themes such as language and meaning, faith and authority, through the medium of the family and its search for the elusive quality of “home” – painfully evident in his most Chekhovian play, Aristocrats. He was concerned with everyday preoccupations rather than the notion of a tragic hero. “You delve into a particular corner of yourself that’s dark and uneasy, and you articulate the confusions and unease, then you acquire other corners of unease and discontent,” Friel once said.

Having begun in 1951 as a short story writer, his work appearing regularly in the New Yorker (1959-65), Friel moved on to radio drama, where he was encouraged by Ronald Mason of the BBC, first in Belfast and subsequently in London. His chief mentor was his fellow Ulsterman Tyrone Guthrie, himself a pioneer of radio drama, who invited Friel to Minneapolis in 1963 to observe rehearsals of Three Sisters for the opening of the Guthrie theatre. Friel called this trip “my first parole from inbred, claustrophobic Ireland”.

Guthrie’s work was the catalyst for Philadelphia, Here I Come! and marked Friel as the father of modern Irish drama. Philadelphia changed the traditional formula, with a split stage, a split personality of the central character, with a public face and a private inner man (in Friel’s words the “conscience, the secret thoughts, the id, the spirit”), and an audience split between reverence for the old ways and the inevitability of the new. Its huge success on Broadway confirmed Friel’s decision to become a full-time writer.

Altogether there were two volumes of short stories, five radio plays, 24 full-length original plays, seven versions of Chekhov, Turgenev and Ibsen, and an adaptation of Charles Macklin’s 18th-century comedy The True-Born Irishman (retitled The London Vertigo, 1992).

Laconic and inscrutable, Friel rarely engaged in public polemics or political and cultural debate. Programme makers, such as his friend Noel Pearson, attempting to portray “Friel the public man”, were hard pressed to assemble a composite portrait of such a figure.

In 1987 he was appointed a member of the Irish senate by the prime minister, Charles Haughey, who particularly asked him to occupy the seat as a northerner, a man of great cultural eminence and one with significant cross-border activity – all three of Haughey’s criteria being met in one person. Friel took the position, as he told me, in order to secure Haughey’s active support for the impending Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, but though he spent two years assiduously attending sessions, he never spoke in the senate.

The fact that Friel seldom gave interviews, especially to eager PhD-hunters, created the erroneous impression that he was aloof, even arrogant. One of the few interviewers whom he trusted was the influential critic Mel Gussow, of the New York Times. Although he discounted the opinions of critics, he knew their importance in the theatre business, and was particularly admired in the US by Frank Rich, and in Britain by Michael Billington. Trust was essential, especially to someone who had grown up within the marginalised nationalist community of Northern Ireland, where he was officially recorded as “Bernard Patrick”, Brian not being recognised by the registrar as an acceptable forename. Officially, “Brian Friel” did not exist.

The impression of Friel’s apparent arrogance was consolidated by his openly dismissive attitude to the profession of theatre director. Despite the fact that his third daughter, Judy, and his wife’s nephew, Conall Morrison, had followed it, he called it “a bogus profession”, responsible only for ensuring that the actors appeared on time and knew their lines. Nevertheless, he had immense regard for three directors in particular: Patrick Mason, Joe Dowling (who directed the Guthrie theatre in Minneapolis, 1995-2015) and Lyndsey Turner of the Donmar Warehouse, London, to whom he gave plays in preference to lucrative West End productions. When he took directorial matters into his own hands, insisting that he should direct Give Me Your Answer, Do! (1997) among others, the results were debatable.

As a friend Friel was loyal and generous. He was not without humour of the driest kind (he gave his hobby in Who’s Who as “slow tennis”), and his letters invariably caught the mot juste apparently effortlessly, a private mirror to the exact eloquence of his plays. But very few knew him: his wife, Anne (nee Morrison), whom he married in 1954, four daughters and a son, and close associates such as the critic Seamus Deane, Heaney (who might have written the line “Whatever you say, say nothing” expressly for Friel), the folklorist David Hammond, the playwright Thomas Kilroy and the actor Stephen Rea. All were involved in the Field Day Theatre Company initiative, which Friel and Rea founded in 1980 and which signalled a new phase of cultural nationalism in Northern Ireland.

Field Day was created largely to detach Friel’s work from the semi-official ambit of the Abbey theatre in Dublin. He immersed himself in the day-to-day running of the company, perhaps to the detriment of his own writing in those years. He resigned from the company in 1994, partly due to differences with Rea but also to allow him to regain some personal freedom.

The need for privacy in fact endangered Friel’s sense of belonging to any group or community. He insisted to me without bitterness but with a wistful and shrewd discontent: “There is no home, I acknowledge no community.” It was an ironic and lapidary statement by a man so honoured and esteemed both at “home” and abroad.

Apart from the fraught periods of rehearsals, life was spent quietly at home in the fishing village of Greencastle, County Donegal, where Friel kept bees (an ambition Chekhov harboured but never realised). But in the rehearsal room Friel was a demon, insisting that voices he had heard at his writing desk (where his characters dictated their lines) should arrive naturally in the mouths of his actors.

The script was sacrosanct. The fact that actors of the calibre of Mason, John Hurt, Penelope Wilton, Tom Courtenay, Jason Robards, Ralph Fiennes and the Romanian performer, director and political figure Ion Caramitru were anxious to play his roles indicates how readily they could discover the essential voice within.

In an 80th-birthday tribute, Heaney noted Friel’s “integrity which allows him to portray so exactingly the search for moral and psychic wholeness”. Friel’s late style, Heaney said, is “that final stage of freedom and mastery when technique is second nature, knowledge of life seems to brim over and there is an uncanny sureness, an ability to give seemingly spontaneous yet entirely authoritative expression to old matters in a new way”. The last plays, especially Afterplay (2002), Performances (2003), The Home Place (2005) and his 2008 version of Hedda Gabler, bear this out plentifully.

Despite a disabling stroke in 2005, Friel was able to enjoy many events centring on his 80th birthday. He received honorary doctorates and other awards, including the Ulysses medal of University College, Dublin, and the title of Saoi (wise one), the highest honour of Aosdána, the Irish parliament of artists, in 2006. When, in 2009, Queen’s University Belfast named its Centre for Theatre Research after him, he joked that it would probably be located in the basement of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry.

He is survived by Anne and four children. His eldest daughter, Paddy, predeceased him.

Brian Friel (Bernard Patrick Friel), playwright, born 9 January 1929; died 2 October 2015

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion