Mary Anning

Palaeontologist (1799-1847)

Before they were even teenagers, Anning and her younger brother discovered the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton in their local cliffs in Lyme Regis, Dorset, in 1811. The discovery kicked off Anning’s life-long passion for finding fossils. As she got older, she would venture out after a storm, often with her dog Tray, hoping that the wind and rain would reveal a specimen amid the limestone and shale. She went on to discover the first complete plesiosaur and a pterosaur. Poor her entire life, Anning was tapped by scientists for her palaeontological discoveries and expertise, but was barred from official scientific circles. Her work was often showcased and published without credit.

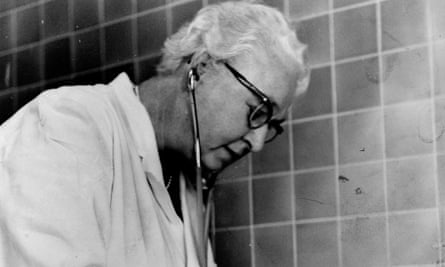

Alice Hamilton

Pathologist (1869-1970)

After receiving her medical degree from the University of Michigan in 1893, Hamilton went on to assess workplace conditions in industries that used lead, mercury and other toxic substances in the United States. When managers were unwilling to turn over information on employee health, Hamilton pulled hospital records, made home visits, and toured manufacturing plants, Ultimately she painted a bleak picture of what unsafe work conditions could do to the body. Lead workers routinely landed in the hospital because of colic, convulsions and weight loss.By the 1920s, Hamilton was the foremost expert on occupational health in the US.

Lise Meitner

Physicist (1878-1968)

In 1944, Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel prize in chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission. Austrian-born Meitner, who both initiated the project with Hahn and offered the insight (with her nephew) that explained Hahn’s experimental findings, was – shockingly – not credited by either the Nobel committee or her one-time partner. Meitner, who was Jewish, had been forced to leave her work at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry and escape Germany in 1938. She ended up in Sweden, without the money or the institutional support to restart her research, but she continued corresponding with Hahn. In 1997 the heavy element meitnerium was named in her honour.

Inge Lehmann

Seismologist (1888-1993)

Working in a country of few disturbances, Lehmann was an extraordinary Danish seismologist. Her detection of some inconsistent patterns in the seismic waves thrown off by earthquakes on the other side of the globe transformed our understanding of Earth: it was Lehmann that discovered its inner core. In 1914, German-American seismologist Beno Gutenberg nailed down the location of the hot magma core below Earth’s mantle, but by the mid-1930s, Lehmann’s data hinted that there was at something else influencing seismic wave trajectories. Not all seismic waves she registered matched up with existing models. In those wonky readings, Lehmann concluded that there must be a solid sphere inside the established core.

Hilde Mangold

Experimental embryologist (1898-1924)

Although it was German embryologist Mangold’s dissertation project that formed the basis of her adviser Hans Spemann’s 1935 Nobel prize for the discovery of the embryonic organiser, he namechecked her just twice in his Nobel lecture. A decade earlier, she had successfully coaxed six embryos to grow into tadpoles with two heads, each with unique genetic makeup. She’d proved that an embryo has an organiser – essentially the chunk of cells responsible for central nervous system and spinal growth – that directs development even when implanted in another embryo. Published in 1924, Mangold’s thesis ushered in a new wave of developmental embryology research, but she died in a gas-heater explosion that same year – a decade before her tutor stepped up to receive his Nobel award.

Elsie Widdowson

Nutritionist (1906-2000)

During the second world war, the British government rationed food and promoted a diet of cabbage, potatoes, and bread fortified with chalk (for its calcium) based on recommendations by Londoner Widdowson and her research partner Robert McCance. At the forefront of a new field, Widdowson’s nutrition research – which included self-injecting all sorts of vitamins and minerals to study their effects – gave us the first comprehensive scientific resource food composition as well as evidence-based recommendations for what we need in our diet to maintain good health.

Virginia Apgar

Anaesthesiologist (1909-1974)

Before the US anaesthesiologist Apgar presented her system of assessing newborn babies in 1953, there was no standardised way to tell if a baby’s health was poor. After the Apgar score came into use, researchers found that certain delivery methods and types of anaesthesia were linked to struggling babies. Realising the opportunities her score gave for statistical analysis, Apgar took a sabbatical to earn a master’s in public health at Johns Hopkins University. She took a position at the March of Dimes mother-and-baby foundation, where she educated people around the country about congenital birth defects.

Chien-Shiung Wu

Physicist (1912-1997)

The Chinese-born, American-trained physicist Wu is best known for disproving a law of nature. The law was the conservation of parity, or the idea that when subatomic particles mirror each other exactly, say, one spinning left and one spinning right, they have to behave identically. In 1956 Wu led a hugely difficult experiment that ultimately revealed this symmetry between mirroring particles didn’t always hold true. With a passion for physics that bordered on obsession, she also worked for the division of war research at Columbia University during the second world war, where she became a highly productive researcher and later professor.

Anne McLaren

Developmental biologist (1927-2007)

An expert in embryonic development and a pioneer of in vitro fertilisation research, in the mid-1950s McLaren and colleagues successfully fertilised mouse embryos outside the womb, coaxed them to an early stage in embryonic development, and then implanted them in surrogates. When the experiment was successful, McLaren sent a telegram from London to a colleague away on holiday: “Four bottled babies born!” In 1982, she was appointed to the Warnock committee, which sought to establish guidelines for in vitro fertilisation in humans. A sharp thinker and clear communicator with a passion for “everything involved with getting from one generation to the next”, McLaren became a dame in 1993.

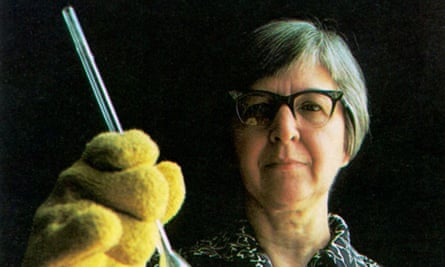

Stephanie Kwolek

Chemist (1923-2014)

Kwolek, the inventor in 1964 of bulletproofing material Kevlar, initially wanted to be a doctor, and began working at US chemical company DuPont in 1946 to earn the money for medical school. But she found the work so thrilling, she never left. She was asked to design a material to take the place of steel in radial tyres. Kevlar was five times as strong – and much lighter DuPont threw resources behind developing the material, and today it is in everything from oven mitts to space craft.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion