For centuries, scientists have wrestled with the deepest mysteries of space, time and the nature of consciousness. But not all of them. Some turn their minds to what can fairly be described as lower-hanging fruit. Like why our knuckles crack when we pull them.

The question has never been the subject of sustained scientific inquiry, but the puzzle crops up in medical literature reaching back more then 50 years. It began, perhaps, with a German physician called Nordheim, who in 1938 demonstrated that most joints in healthy people can be made to pop when pulled upon.

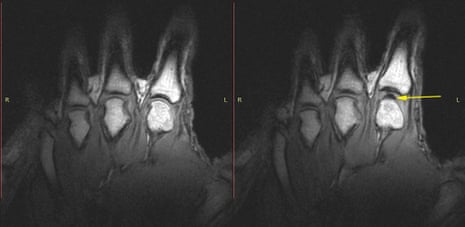

In a report published today, Canadian scientists tackle the problem with 21st century technology. With an MRI scanner, a bespoke finger-pulling device, and a gifted and willing knuckle-cracker, they set about recording the first video footage of the innards of a knuckle being cracked.

“It’s such a common thing. Some people do it habitually. They love it. Other people find it repulsive. But there’s always been this argument over what actually happens to make the noise,” said Greg Kawchuk, professor of rehabilitation medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Kawchuk launched his study after a local chiropractor, Jerome Fryer, came to him with a new explanation for knuckle cracks. “It didn’t seem like we needed another idea,” Kawchuk said. “What we needed was to look inside the joints to see what was going on.”

In 1947, a pair of doctors at St Thomas’s Hospital in London performed their own investigation into the nature of knuckle cracks. They tied a cord around volunteers’ fingers and got them to tug until the joint went pop. They captured it all with x-ray images. A tension of about 7kg was needed to elicit a pop, during which the bones in the knuckle separated by about half a centimetre.

The doctors concluded that the crack sounded when the joint surfaces were suddenly wrenched apart. This caused a sudden drop in pressure in the synovial fluid between the joints, and the formation of a vapour cavity, or bubble. One cracked, it took 20 minutes of rest before the same knuckle would crack again.

The explanation stood for 24 years, until 1971 when a group at Leeds University challenged the idea. They essentially repeated the London experiments but reached a different answer. The crack came not from the bubble forming in the joints, they argued, but from the bubble quickly collapsing. In science, detail is everything.

Fryer turned out to be adept at cracking his knuckles, and volunteered to have each of his ten fingers pulled, one by one, until they popped. To capture the process in action, each crack took place with Fryer’s hand in an MRI scanner.

Writing in the journal, Plos One, Kawchuk describes how every crack occurred as the joints suddenly separated, and a gas-filled pocket appeared in the synovial fluid that lubricates the joint. The bubble comes from gas that comes out of the fluid as the pressure in it drops, just as bubbles appear in freshly opened bottles of fizzy drinks. “If you’ve ever washed up glass plates, you’ll know they can be hard to separate when they are wet. The film of water between them creates a tension that needs to be overcome. It’s similar with joints. When you pull on them, they resist at first, and then suddenly give way,” said Kawchuck.

The results suggest that the London doctors hit on the right explanation in 1947. Kawchuk does not rule out other effects though, that were not picked up by the MRI scanner. “We have to be cautious,” he said.

But what use is the answer? Apart from solving, perhaps, a long-standing mystery, Kawchuk said the work could potentially help doctors understand why some people can crack their knuckles and others not. “The ability to do this can sometimes change in people over time. Maybe we can use it to ascertain the health of their joints. It could give us fresh insights,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion