Norma Desmond has a lot to answer for. The image of the fading silent film star as a deluded recluse, living in gothic isolation, is seductive but far from reality.

Many silent film actors went back to work in the talkie era, while others retired, having begun working in the 1900s or 1910s. Some moved behind the scenes or revived their careers on stage or TV, or made memorable returns to the big screen in later life – think Lillian Gish cocking her rifle in The Night of the Hunter. Many Hollywood stars lost their fortunes in the Wall Street crash of 1929; others turned to unprofitable business ventures or to drink and drugs. But few lived as the heroine of Billy Wilder’s brilliant Sunset Boulevard does, in seclusion in a Los Angeles mansion, fruitlessly dreaming of a comeback.

Many of the era’s most famous stars lived long lives after their first fame. Charlie Chaplin died on Christmas Day 1977, and Mary Pickford in 1979. Louise Brooks and Gloria Swanson died in the 80s, Gish and Greta Garbo in the 90s. Mickey Rooney, whose career began in the silents, died in 2014, and Jean Darling, a veteran of the Our Gang shorts, died in September this year. The 2015 Pordenone silent film festival was dedicated to her memory.

But the film industry has not always been kind to the silent era. It was tricky to whip up excitement about the new world of synchronised sound while admitting that, actually, the old movies were pretty great. There are sad stories of films being mislaid, melted down for their silver content, or cut up and used for stock footage. Interest in the silents wasn’t revived until the 50s at least, and then only gradually. The world turned its back on the silent stars, rather than the other way around.

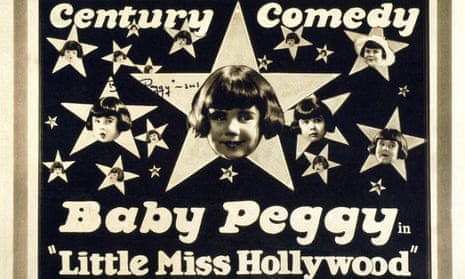

Earlier this year, the Guardian interviewed one of the last remaining silent film actors. Diana Serra Cary was one of the silent era’s biggest stars, a greatly loved child actor who went by the name Baby Peggy. One of the many remarkable things about 97-year-old Cary is that she doesn’t seem to be bitter about the way she was treated by the film industry and her own family. Pushed in front of the camera aged just 19 months, Cary slogged her way through more than 150 films, both features and shorts. She made tremendous amounts of money but most of it went to other people, and the rest was lost when her family went bankrupt. The films she made, boisterous numbers that delighted audiences in the 1920s, were largely destroyed.

Cary recalled in that interview that her expressiveness, which was remarkable for such a young performer and indelible on screen, was in part due to her obedience to her father. He had hoped for a movie career of his own, and when that failed, it was up to Cary to pursue his dream. Naturally, she did precisely as she was told. “My father would snap his fingers and say, ‘Cry!’ And I would cry. ‘Laugh!’ And I would laugh.”

After a brief stint in vaudeville, and an even briefer screen comeback as a teenager in the 30s, Cary has largely devoted her life to writing and to improving the conditions of other child actors. She wrote a book called Hollywood’s Children on the subject, and her campaigning with fellow silent child star Jackie Coogan led to the California Child Actor’s Bill (or “Coogan Law”) – which regulates child actors’ pay, education and time off.

More recently, Cary has been digging out her old films and accompanying them on the festival circuit, talking to a growing second fanbase about her career and her campaigns. Recent exemplary DVD releases from Milestone Films and Undercrank Productions allow 21st-century viewers to see what the Baby Peggy fuss was all about.

Paired in her first films with a performing dog named Brownie, before striking out alone, Peggy is an adventurous tomboy with an impish grin and a precocious certainty about her gestures – a genuinely great movie actor, just kindergarten-sized. The documentary Baby Peggy: The Elephant in the Room, also available on disc, tells Cary’s story in her own words, from her remarkable childhood to her writing career.

Cary is treasured by a generation of new fans as an advocate for child actors’ rights and for the silent era itself, as well as for having the dubious honour of being the last remaining megastar from the 20s. But now her fanbase is getting angry. Since 2012, there has been an online campaign to get Cary a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame – which would seem about right for a woman who received a million fan letters – but so far to no avail.

And last week, Cary’s fans were distraught to learn that her request for medical assistance from the Motion Picture and Television Fund, a benevolent charity for the entertainment industry, had been turned down. Fans contacted the fund via email and Facebook to voice their outrage in great numbers, but as yet the decision has not been reversed. Cary explained in a statement that: “When I first contacted the MPTF more than six months ago, I never doubted it would help me. I myself stood beside Mary Pickford when the Fund was first established [in 1921], then worked on its behalf helping the needy as a teenager during the worst days of the Great Depression.”

When we talk about silent cinema, we talk a lot about lost films, and the sadness that there are so few people alive who can tell us what is was like to work in the industry, or to watch those movies when they were first released. Cary’s first contribution to the silent cinema was to make joyous movies. Her second has been to help preserve silent films and improve our understanding of the time in which they were made. Whether with a star on Hollywood Boulevard or some help in her own home, the time is right to repay our debt.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion