Editor’s Note: Dennis McCormack is one of the original Navy SEALs and a veteran of the Cuban Missile Crisis and Vietnam War. George S. Everly Jr., a pioneer of modern stress management, is associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Douglas Strouse is a specialist in organizational management. They are the authors of “STRONGER: Develop the Resilience You Need to Succeed” (AMACOM, 2015). The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors.

Story highlights

In the Oregon shooting, Chris Mintz became a national hero by trying to block a gunman

Acts of heroism happen under duress, and no one can predict them, authors say

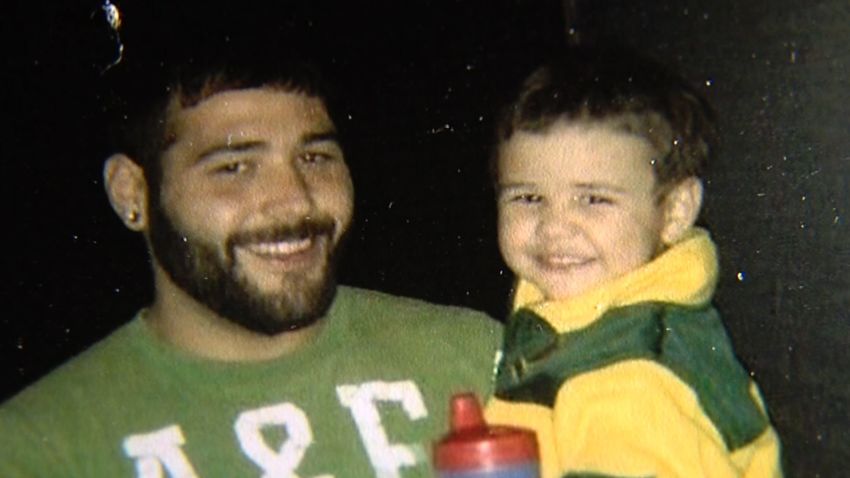

On October 1, 2015, Chris Mintz became a national hero.

During the shooting rampage at Umpqua Community College in Oregon, Mintz, an Army veteran, rushed to block the door to a classroom the gunman wanted to enter. The gunman igmored Mintz’s plea that, “It’s my son’s birthday today.” Even after he was shot multiple times and was lying wounded on the floor, Mintz still tried to persuade the gunman to stop his attack and avoid a slaughter. Mintz survived seven bullets, which is lucky to the point of miraculous.

A hero is someone who, when confronted with the gravest danger, thinks of the safety of others above himself. Heroes would tell you that they are “called to action.” Heroes are not made, heroes simply are. There is no training that could prepare one to be a hero, as his extraordinary and brave actions seem reflexive or automatic.

When you’re faced with a life-or-death situation, you don’t have much time to pause and think: Should I block the door or not? Should I fight the gunman or not?

Acts of heroism happen under duress, and no one can predict them.

Over a month ago, three Americans and a Briton heard gunshots on board a high-speed train to Paris. The four ran toward the attacker to subdue him and avoid a massacre. The attacker had an AK-47, a handgun and a knife. The Americans and Briton were all unarmed. They managed to overpower the attacker and save the train full of passengers. That day, they proved themselves heroes, too.

What is it that heroes possess that enables them to effortlessly act in this manner?

For one thing, heroes don’t take time to analyze a situation. They do what they think is right, fair and just. They don’t view themselves as special; they are selfless, not egocentric.

Most of us are not predisposed to act in heroic ways, though.

Dr. Philip Zimbardo, a psychology professor at Stanford University, conducted a study where he discovered that out of 4,000 people, only 20% were inclined to act heroically in an emergency, i.e., voluntarily helping those in need with recognition of potential risks and costs and no expectation of gaining anything in return. Heroism is more than just compassion, Zimbardo found, it is “the antidote to public indifference and systemic evil.”

Another study suggests people do not feel the inclination to help others depending on the circumstance. Social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley conducted research that shows the more witnesses there are in a situation, the less likely they are to help someone in need. This phenomenon is called the “diffusion of responsibility” or “the bystander effect.”

What’s interesting about Mintz, Martin, and two of the three Americans is that all of them were or are U.S. service members. It seems like their call to action began long before it was time to act. Perhaps, to some degree, heroes are a self-electing group. These are people who feel compelled to risk their lives to save others.

As Navy SEAL Moki Martin, who received a medal for valor of service in Vietnam (the mission was declassified only after 35 years), said aptly at his award ceremony, “I accept this award on behalf of all of you from Alpha Platoon. …This award is for all of you.”

Martin was second in command of his platoon off the coast of North Vietnam, where his team rendezvoused with a submarine to conduct a mission. Unknown to Martin, his team jumped from a helicopter at a height of 50 feet instead of 20, with speed far beyond the expected 20 knots. Martin’s lieutenant died on impact, and a team member was rendered unconscious. Martin was also injured, yet he managed to pull his team together, inflate the unconscious member’s vest (saving his life), retrieve his commander’s body, and swim to safety. A true hero, Martin recognized the role others played and downplayed his own actions of bravery.

Many people dream of being heroes. But wanting to be a hero and acting like a hero are completely different things. At the very least, people like Chris Mintz will inspire us to be more selfless and valiant, and to try to think of others ahead of ourselves.

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.