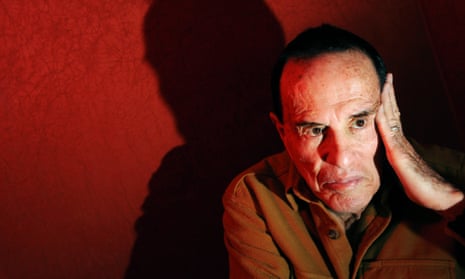

Branding and product placement cast dark shadows over everyone eventually – even occultists such as Kenneth Anger, who this weekend debuts a new gallery project, Lucifer Brothers Workshop, at the Art Los Angeles Contemporary fair in Santa Monica, California.

Anger, at 88, is best known for his Magick Lantern Cycle, a series of spooky but highly influential films, including Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) and Scorpio Rising (1964), and for being a tutor to students – among them guitarist Jimmy Page – in the work of Aleister Crowley and Thelema, the Satanic religion he developed.

“Not Craugh-ley,” Anger corrects. “Crow-ley. As in un-holy Crow-ley”. It’s a correction Anger – who can be as sharp as his name suggests – has doubtless been making since the 1950s when he first developed his lifelong interest in the notorious English occultist, ceremonial magician and mountaineer.

The purpose of Anger’s ALAC show is in part to shift $300 bomber jackets with “Lucifer” emblazoned across the back, a replica of one worn by Leslie Huggins in his classic Lucifer Rising. It’s also to introduce art fair perusers to the work of two women, Rosaleen Miriam “Roie” Norton, an Australian pantheist known as “the Witch of Kings Cross” and the better-known Marjorie Cameron, a flame-haired woman once married to Jet Propulsion Lab scientist Jack Parsons, the man whose occultist LA-based group, The Gnostic Mass at the Church of Thelema, briefly included Scientology founder L Ron Hubbard in its congregation.

In recent years, Cameron’s art, often inspired by visions, has become more widely known and she was recently the subject of a show at MOCA. Anger directed Cameron in a number of films, including Lucifer Rising, and the pair lived together over two years in the 60s.

“She was extraordinary – a genuine witch,” Anger says matter-of-factly. “She had powers. Unusual powers. Extra powers. She kind-of knew things before they happened. She loved a full moon.”

During their time living together, Anger was able to observe Cameron at work; she painted Anger as Saint Sebastian nailed to the ground with swords. “She considered them talismans. In her lifetime she never sold anything. She didn’t want to be a commercial artist. She had a couple of gallery shows but insisted they were not for sale.”

Mysteriously, Cameron destroyed much of her work. “If she destroyed some of them, it was for magical reasons that [she] consigned them to the flames. Of course, this sounds insane. If I’d been there I’d have tried to stop her. But it was her business she wanted to do that.”

The half-dozen pictures in the show, including a limited edition of a Crowley print “Do What Thy Wilt”, are organised by Anger’s aide Brian Butler.

In his opinion, Cameron was a bad influence on her husband, who died in a mysterious explosion in 1952, while packing to go on holiday, and who has now been largely written out the history of rocket development. “She turned him on to Satanism. She was very dominant. The FBI’s assessment was that she’d ruined him.”

Anger’s history with the occult dates back to 1955, when he visited and helped to restore Crowley’s former temple in Cefalù, Sicily. The relative paucity of material suggests the business of occult-inspired art is no longer flourishing in the way it may have been in the late 60s, when Anger associated with the Rolling Stones, and when he and Marianne Faithful travelled to Egypt to make Lucifer Rising and a small vanity mirror filled with heroin.

Anger anticipates the exhibition will in small measure add to the notoriety of Rosaleen, Cameron and Crowley. “The occult is an undercurrent, it never quite goes away,” Anger explains.

But where to find it? Los Angeles has had more than its share of dark moments. Anger was friends with Manson family recruiter and musician Bobby Beausoleil, who is serving a life sentence for the murder of music teacher Gary Hinman in 1969.

“I’m sorry Bobby did something that caused him to get locked up,” Anger says.

As a longtime resident of Los Angeles – he can recall seeing a Nazi Zeppelin moving up the coast prior to the second world war – he has a long perspective on Tinseltown, and is the author of Hollywood Babylon, a salacious tome that served up the sleaziest gossip about the movies’ golden age. The current debate over diversity in films, he says, is entirely new.

“Nobody thought about it before or if they did think about it they didn’t talk about it. It’s a good thing. Hollywood was always liberal, but film-making was always a white phenomenon.”

Still, from a surface reading of LA culture now, of the Kardashians and juicing diets, it’s a hard to detect much by way of occultist activity. “It’s always been there and it always will, but I can’t say it’s zooming up to the surface right now,” he says.

“It’s still going on because Crowley is an inexhaustible subject. There’s so much more in his work to uncover and I still read his work occasionally. But I don’t need to practice spells and rituals.”

- Kenneth Anger is speaking about art and Thelema at Art Los Angeles Contemporary on Saturday at 3.30pm. ALAC continues through Sunday at Barker Hangar Santa Monica airport

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion