Animal Behavior

How Social Contagion Helps Explain Our Pet Choices

In 1939, Londoners killed 400,000 dogs and cats in four days. Why?

Posted August 18, 2017

On the afternoon of September 3, 1939, thousands of dog and cat owners in London began to kill their pets. Over the next four days 400,000 companion animals were euthanized, most in veterinary clinics. The carnage was triggered by the announcement that Britain had declared war on Germany. Approximately 25% of the companion animals in London were killed that week, a death toll that vastly outnumbered the total number of Londoners who died in the Blitz. Pet-killing was not mandated by the government. Nor was it a reaction to enemy bombing of London, which only began a year later. Predictably, the slaughter was soon followed by a backlash. By spring, many owners were, in the words of historian Philip Ziegler, “regretting the holocaust of pets that occurred at the outbreak of the war.” This largely forgotten episode in the history of human-animal relationships is recounted in The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War II’s Unknown Tragedy, a fascinating new book by historian Hilda Kean. While it happened nearly 80 years ago, this tragic incident has implications for a current animal welfare issue.

For several reasons, the cause of the London dog and cat massacre is elusive.

- There is no evidence that Londoners who had their pets killed were acting out of blind panic or “war neurosis.” Indeed, according to Kean, morale in London remained generally high in the first days after war was declared.

- While veterinary clinics ran out of chloroform to euthanize pets, there were no shortages of food or shelter for pets.

- Organizations such as the RSPCA tried and failed to talk many people out of euthanizing their healthy dogs and cats.

- Britain long had a reputation as a nation of pet lovers, and by the 1930s, the British were increasingly viewing pets as family members. (There is no evidence that any Londoners killed their children in response to the declaration of war, though many were sent off temporarily to the countryside.

A possible answer to the question of why people euthanized their pets is that they were afraid of the fates that would befall their beloved dogs and cats if their island was invaded or bombed. This view is illustrated by a woman who wrote “My granny had her cat put down at the beginning of World War Two because she didn’t want to think of her cat as wandering around homeless and afraid.” Kean, however, does not offer a tidy explanation of the massacre. Rather, she emphasizes that 75% of Londoners did not kill their pets, and whether pets lived or died was the result of individual decisions by owners based on “prior existing relationships within a household.”

But I think the London pet massacre may have been a fad spread by rapid social contagion.

Pet Euthansia as Social Contagion

A fad is defined as “any form of collective behavior that develops within a culture, a generation or social group and which impulse is followed enthusiastically by a group of people for a finite period of time.”

Examples of pet fads abound. When I was a child, every kid in my neighborhood had pet baby turtle. (Who knew that they carried salmonella?). Recent pet fads in the United States have included spikes in the popularity of ferrets, miniature pigs, hedgehogs, sugar gliders, clown fish and even pet rocks.

The AKC Studies: What Dog Breeds Reveal About Social Contagion

Over the past 10 years, my colleagues and I have explored how fads spread through cultures by examining the rise and fall in the popularity of dog breeds. These studies were based on analyses of 60 million purebred puppies registered with the American Kennel Club between 1927 and 2005. We have found that shifts in our collective preferences for pets are influenced by the same factors that determine what is hot in the latest sneaker styles, baby names, and pop songs.

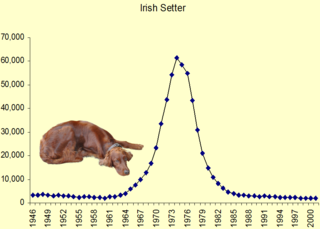

—As shown in this graph, breeds like Dalmatians, Irish Setters, and Rottweilers show the boom and bust patterns characteristic of other fads spread by social contagion. In these breeds, the cycle from from the start of the boom to the end of the bust takes about 25 years.

—Surges in the popularity of dog breeds can be set off by hit movies. (The Harry Potter movies even sparked an increase in pet owls in the UK.)

—Like baby names, choices in popular pets follow the “laws of fashion cycles.” This means that the more rapidly a breed gets hot, the speedier its fall from popularity.

—Also like baby names, the most popular dog breeds constantly shift at a regular rate.

—Breed popularity is more a matter of fashion rather than function. For example, breeds that have lots of genetic problems or behavioral issues are just as likely to become popular as dogs that are healthier and easier to live with.

Enter the French Bulldog

The last point is exemplified by the French bulldog. For 60 years, the popularity of French bulldogs languished. For example, in 1927, 505 French bulldog puppies were registered with the AKC, and in 1987, a mere 412 puppies were registered. But then, like Dalmatians and Irish Setters, their popularity began to increase at an exponential rate, and it only took 10 years for them to jump from the 38th most popular breed in 2005 to the 6th most popular breed in 2015. The little dogs did not become suddenly popular because they were “better” than other breeds. Indeed, Frenchies display the plethora of genetic problems that plague brachycephalic (“flat faced”) breeds such as pugs and English bulldogs. As one veterinarian recently wrote of these animals, “Every structure that should make up the nose has been squashed flat. The only time these dogs are not in some degree of respiratory distress is when you have them intubated under anesthetic.”

I am suggesting that the craze for flat-faced dogs was produced by the same collective mob mentality that produced the slaughter of nearly half a million pets in 1939. Both the pet massacre and the bulldog fad resulted in massive animal suffering. The difference is the speed of the cycle. It only took a few days for the London pet slaughter to run its course. But based on our studies, it will probably take 10 or 12 years for French bulldogs to return to their historic modest level of popularity. The good news is that veterinarians and animal protection organizations are now campaigning against ownership of French bulldogs and other brachycephalic breeds. The bad news that the demand for genetically deformed flat-faced cats is on the rise.

Even Kim Kardashian has one.

Post Script: For an excellent discussion of The Great Cat and Dog Massacre see this essay by Colin Dickey.

* * *

Hal Herzog is professor emeritus of psychology at Western Carolina University and author of Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It's So Hard To Think Straight About Animals.