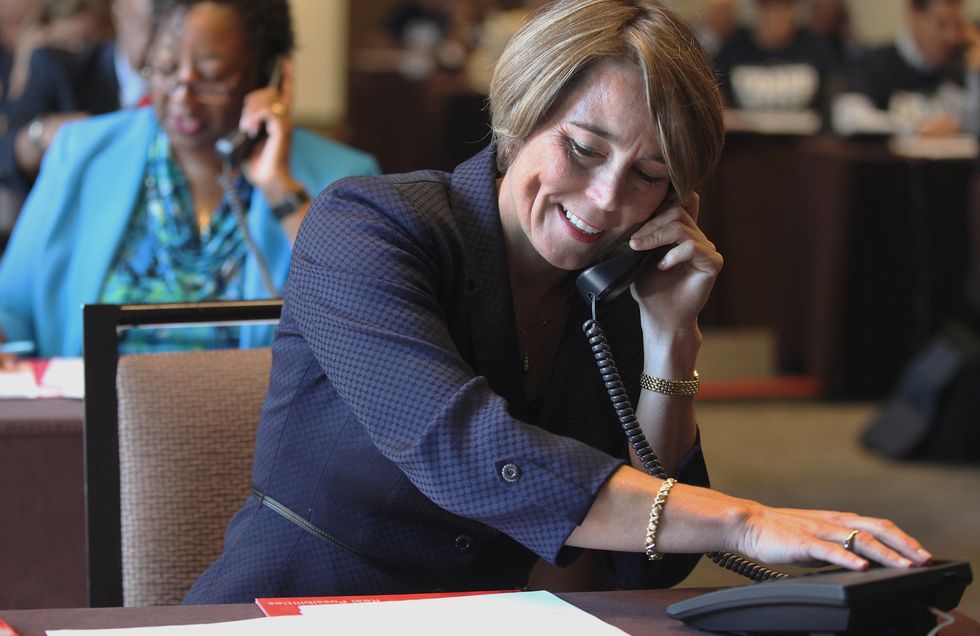

Last Friday, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey held another in a series of town halls that she's scheduled around the Commonwealth (God save it!) to talk about her job and her role as attorney general in opposing certain policy initiatives of the new administration. It already had been an eventful day: Healey had been subpoenaed by Congress. Again.

Even before the president*'s inauguration, Healey had taken the lead on a national issue of some import. When Inside Climate News published documents alleging that Exxon Mobil had known about the impact of fossil fuels on climate change for decades, but had engaged in a systematic campaign of denial and disinformation, Healey and attorneys general from 14 other states and the District of Columbia banded together and pursued a fraud investigation against the company that was patterned, to an extent, on the various legal tactics that were arrayed earlier against the tobacco companies.

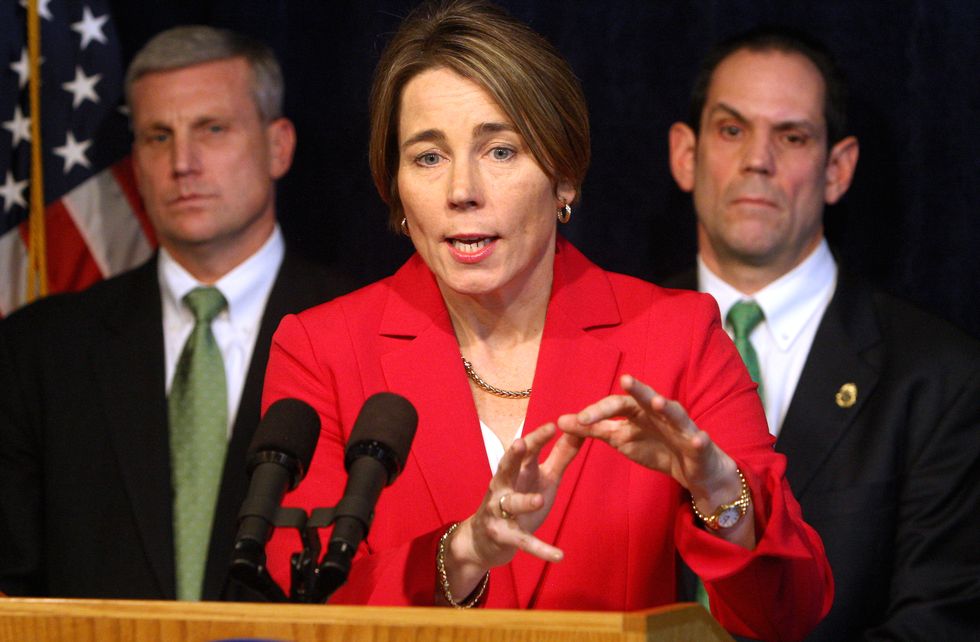

ExxonMobil responded with an extraordinary lawsuit in which the company charged that Healey's investigation violated the company's First Amendment right to free speech and its other constitutional liberties by judging the case before investigating it. (Corporations are people, too, my friend, as another former Massachusetts state official once said.) That case is pending. But it caught the attention of Rep. Lamar Smith, Republican of Texas, the incoming chairman of what is laughingly called the House Science Committee.

Last July, he subpoenaed Healey and Attorney General Eric Schneiderman of New York to testify before his committee, charging that the two of them had, in his words:

"…appointed themselves to decide what is valid and invalid regarding climate change. Attorneys general are pursuing a political agenda at the expense of scientists' rights to free speech."

Healey had declined that invitation but, last Friday, Smith had issued another one, which she also declined.

Since then, of course, we inaugurated a new president* and Healey has found herself at the forefront of the formal resistance against what he's been doing. She jumped to the defense of the immigrants caught at Logan Airport by the administration's ill-conceived and badly executed executive order, and she once again joined other AGs in a lawsuit against the immigration ban. At the same time, she's also embroiled in an ongoing battle with the NRA over an enforcement notice she issued regarding copycat assault weapons. The NRA is lobbying all over Beacon Hill in favor of two bills, one of which would strip the AG's office of any power to regulate firearms. She's been busy.

There is little question that Healey has ambitions, and that she's a rising star. A former point guard at Harvard, she played basketball professionally in Europe. She is the first openly gay attorney general elected anywhere in the United States. But she is also emblematic of a larger phenomenon. With the Democrats outvoted almost everywhere in Washington, and with the Republicans there apparently willing to tolerate almost any strange behavior from the White House in pursuit of their agenda, the only Democrats with the most real power to throw sand in the gears are local officials—mayors, city councils, and state attorney generals.

If nothing else, this wrong-foots generations of conservatives who insisted that local government is the best government. The defenders of state sovereignty are trying to get Maura Healey, and those like her, off their case. Good luck with that.

Suing the president isn't what you signed up for, is it?

The nature of my job has not changed, but we do have more on our plate right now. Look, I'm somebody who worked very hard for Hillary Clinton and was very disappointed with the results. And now we see the consequences and the impact. And I thought, frankly, it would take a little longer to see some of that. I did not and could not have imagined that we would be in federal court within days after the inauguration, but that's unfortunately where we are.

And that was over the immigration thing.

That was over the immigration thing. Although I have to say, we actually filed three cases before that, because we recognized that for some of our work as it relates to consumers and the environment and students, the fights we've been waging and some of the gains made are now totally at risk with this new administration. So we filed in ongoing court actions where the Obama administration, the Department of Justice, had been defending those efforts. We recognize that this new administration might just back out of the case all together. We needed to file as state attorneys general to be able to make sure that somebody was making those arguments and standing up for people.

Were you woken up in the middle of the night for what was going on at Logan Airport? Were you still at the office?

The news came down late Friday afternoon. I happened to be at a meeting of state AGs down in Florida, actually. And it was a regularly scheduled meeting of the Democratic AGs and so we were there and a big part of the agenda was talking about and thinking about what our teams and offices needed to be prepared to do. Conversations that, frankly, we started right after the election.

I remember a few days after the election, picking up the phone and calling some of my colleagues. And we get together, some of us, in the fall, a couple of times after the election. And then there was this meeting down in Florida. It was amazing to be sitting there talking about these issues, and all of a sudden across our phones comes news that he's done it! He's made good on his promise of a Muslim ban, and here's the executive order. So then, over the next 12 hours, you're on the phone to our staff. I and others put out statements denouncing the executive order. I got on the phone to my lawyers, who had been thinking that this might happen but really had to do quick work.

So you were still in Florida?

So I was still in Florida, flying back the next day. I had people from my office on the ground at Logan talking to the lawyers who had started to gather, and others who were there. So when I touched down, I immediately went from the terminal that I landed on JetBlue, over to Terminal E, the international terminal at Logan. I immediately started talking to the folks there, and then over the next 72 hours, the teams worked very hard to get together the filings. The next morning, a few of us AGs were out with a statement, and then in court. It's just been a fast and furious couple of weeks.

What was the basis on which the Massachusetts court ruled differently than the court in the Ninth Circuit?

Well, it's different in that it isn't a complete ruling. As much as the President tried to talk about it as a win, it was not that. Basically, all the court ruled is that it wasn't going to extend the restraining order that was in place on the ban because, as a practical matter, what had happened by that time, is those people had come through the vetting process and were here in Massachusetts, so we have yet to actually file our complaint.

We moved to intervene, and we filed a number of declarations that we quickly put together. We had tremendous outpouring of support—business leaders, healthcare leaders, academia at major colleges and universities. We worked closely with our client agencies. It was incredible.

And you had the lawyers who were like firemen the night it came down, right?

My lawyers and lawyers across this country worked like crazy to get into court. I was incredibly proud. That, to me, is a reminder of why I went to law school, it's a reminder of what it means to live in a country where there is rule of law—how important it is that we have an independent judiciary. And I kept getting reports from them, but the team worked literally around the clock.

I spoke to Senator Warren in the Capitol the night of the vote on Jeff Sessions, and what came out of the conversation is that state AGs are in a better position to act than senators right now—because senators need the votes, and they don't have them.

Well look, our job is to enforce the law, and you're going to see that happen in a couple of ways. First of all, particularly given that President Trump's cabinet appointments have tended in the direction of people who have spent their careers looking to dismantle the very agencies that they seek to head—and if not to dismantle them, at least have worked adverse to the policies and interests advanced by the agencies—you know you're going to have a real problem. So what does that mean? It means that state AGs are going to enforce the laws around protecting workers and consumers and civil rights and the environment—you name it.

The other thing is that we are going to be there to hold this administration accountable, to sue the President and to sue his administration. You've seen it already. Unfortunately, you're going to see it again, because I don't think he gets it. And I don't think he understands the responsibility, the gravity of the position. So far he has only created chaos, and as I see it, it seems to be a chaos born out of an ignorance and irresponsibility. So, it'll be the role of the state AGs to use the rule of law and the courts to hold him accountable.

And it's all Democratic AGs at this point?

Yeah, it's all Democrats. I have to get you the exact number. We probably have a working group of about 20 Democratic AGs who are working really well together. We always work well—I mean, we work together on a lot of issues, right, multi-state matters. But boy, talk about a galvanizing event. It's like you're down 20, and you're coming out at halftime. It's like do or die, here we go.

Are you wary of a national profile? I mean, is it not what you signed up for?

I don't pay these things too much mind. It is what it is, you know. Look, I everyday just try to do my job in a way that I think is the way I'm supposed to be doing it.

And you were in court against Exxon before the election, right? That predates the election?

Oh, yeah. We've been in court on a few things. And I understand it's partly a result of the nature of the fights that my office has been involved in, they're not things that I've sought out. But when you do things like enforce a state law around assault weapons, you see that there are some people who aren't happy about that and that's a national issue.

I didn't know that Exxon had sued you.

They even used my middle name. It was very personal.

Is it still in court?

Yeah, but in one court we've won. The Massachusetts court ordered them to produce the documents. As I say, it was pretty remarkable—and this is a good illustration, right? The same day that Rex Tillerson is testifying before Congress, refusing to answer questions on what Exxon knew and when about climate change—as a result of our having sent a subpoena to them and then them having sued me, and our filing the papers saying, "No, you've got to produce the documents," we get that order from the court ordering them to produce the documents.

As a result of his testimony, or just as coincidence?

No, separately because—my point is, as far as the role of or the efficacy of state Attorneys General, I think it's a good example of that. My office sent a subpoena to Exxon back in April. Now, instead of responding how companies normally do when you send them subpoenas asking for information—their lawyers get on the phone with our lawyers, they make a deal, and then they produce our documents. No, no, they raised—they've gone a complete all-out war against our office, filing not one, but two lawsuits. One in the hometown district in Texas, and a second one up here.

And it's against your office? It's not against the other people involved?

No, because it's New York and our office that have actually sent subpoenas. They sued me but they didn't sue New York initially—I'm not sure what that was about. But now they've joined New York. But they actually were the ones that had taken us to court, which is remarkable, right? And there was a great article about the impact of Citizens United—this whole notion that a company has free speech rights, and now companies are looking to use that to say, "Hey, you, state AG—you're asking us questions about what we knew and what we said interferes with our corporate right of free speech." It's just crazy.

That's their argument?

That's their argument. So, that's a pretty dark day if that ever becomes precedent. It's a pretty dark day for corporate accountability. That's kind of what we are, we are representing the people. And I worked in private practice, you know, at Hale and Dorr for many, many years.

Oh really? I didn't know that.

Oh yeah, I was a business lady.

At Hale and Dorr?

Yep. I got out of college, played ball overseas, came back, went to law school at Northeastern. I clerked for Judge Mazzone, who is the judge who ordered the cleanup of the Harbor—great guy. He was a Harvard football player, he was an end from Everett. He played on the Everett teams in the 50s, and then was at Hale and Dorr for about 8 or 9 years as a business litigator. So I represented corporations, like I understand this space. And then joined the AG's office.

So Rep. Lamar Smith sent you a subpoena today?

Yes, the second time. We've already been through this. We've already told him no thank you.

And this is connected to Exxon?

Oh yeah. It's his district. He chairs the Committee on Science and Technology, which I find an ironic name, given that the majority have taken positions that are away from science. But, in any event, yeah, this part of the multi-level campaign against my office, in what is simply an effort to do our job.

So here's what happened: Exxon sues, and then Lamar Smith and the committee send us a subpoena, maybe around this summer. We respond saying, "No, we're not going to"—they wanted all our documents and information about how this came to be, who we talked to, why we're doing this. We said you know, this has never happened before. They have never subpoenaed a standing attorney general in history. So they do it to me. We said, "You guys don't have authority to do that. We're not producing documents and information." Go away for a while.

And then, they renewed their requested today and we got a new subpoena, which we will respond with what we said before. It hasn't changed, guys, like they don't have any authority to do this. And what this is and why it's so galling is that it's just an effort to chill an investigation by a law enforcement agency.

Yeah, and the people you're talking to—to chill the witnesses and the whistleblowers.

Oh yeah, because they've also subpoenaed the scientists and organizations and others, and that's really troubling. That's really troubling to see. So, we'll continue to do our job and press ahead.

Where is that lawsuit? That lawsuit's in court in Texas?

We're in a federal district court in Texas. The judge there has yet to rule on our motion to dismiss. That's what we filed, a motion to dismiss Exxon's action. In the meantime, it's good that Massachusetts court ordered them to comply. So we'll see, but it's been interesting.

This post has been updated.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page.

Charles P Pierce is the author of four books, most recently Idiot America, and has been a working journalist since 1976. He lives near Boston and has three children.