The first modern writers to bring animal behaviour and biology to the general public were Konrad Lorenz and especially Desmond Morris with his international bestseller The Naked Ape. These 1960s books paved the way for other popularisers, including EO Wilson, Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, Jane Goodall and myself. We are now very used to this kind of literature, but I still remember how my professors at the time warned against reading Lorenz and Morris, fearing that it would muddle our minds. They should not have done so, though, because we took their warnings as recommendations.

I met Morris when he came to open the chimpanzee facility at Burgers’ zoo in Arnhem, in the Netherlands, where I conducted my studies. Seeing the water moat surrounding the ape island, he predicted, tongue in cheek, that the chimps would one day build a raft to get out. They never did (chimps are hydrophobic), but the entire colony of 25 apes did escape a few years later by propping a tree stem against a concrete wall and climbing over it, upon which they raided the zoo restaurant. Returning home with their bellies full, they left the zoo staff – and me – wondering how they could have done so without tight coordination. The tree was way too heavy for a single chimp.

This event interests me nowadays for different reasons. It has become customary to claim that only humans cooperate with insight and joint intentions. But I hold animal intelligence in much higher esteem. My latest book Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? laments the persistence of human exceptionalism. For about a century, we have tried to squeeze everything other species do into two small boxes: learning and instinct. We now have outgrown these boxes and are willing to consider a much wider range of possibilities. Animal capacities are often similar to ours, but can also be quite unique. Since we use ourselves as touchstone, we downplay capacities that we don’t possess, such as echolocation or magnetic navigation, while excessively admiring those we rely on, such as language. With this in mind, here – chronologically – are a few linguistic products that have influenced my thinking:

1. The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli (1532)

While watching chimpanzee power struggles at the zoo, I found zero help in my biology books. So I turned to Machiavelli, reading him during the quiet hours in between the upheavals of bluster and aggression that the chimp males produced. Machiavelli was clear that (military) might is crucial for any ruler, as are strategic alliances and backing from the masses. In chimpanzees, too, no alpha male rules on his own: he needs to make deals, and pay off his supporters. The Florentine chronicler of human affairs helped me see the patterns that I described in Chimpanzee Politics in 1982.

2. The Mentality of Apes by Wolfgang Köhler (1924)

This book started the cognitive revolution, at least for animals. It describes in detail how chimpanzees solve problems in their heads. Köhler presented his apes with a brand new problem, such as a suspended banana, and noted how they would stare at it for a long time before suddenly jumping up to stack up the boxes he had provided. They reached the solution on the basis of einsicht, translated as “insight”. This radical proposal made Köhler a hated man – many scientists still cannot speak his name, only hiss it. Yet he ushered in an era of research that now includes corvids, dolphins, elephants, parrots, and other brainy animals considered as thinking beings.

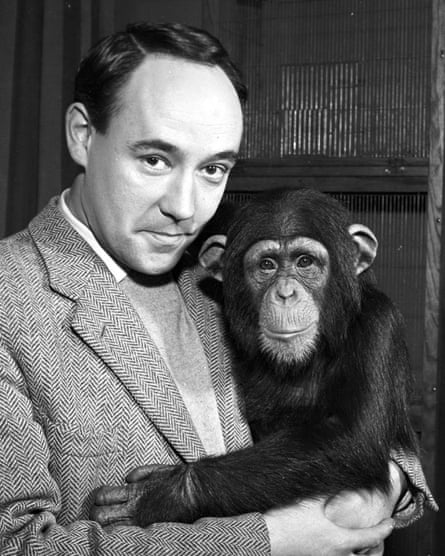

3. The Naked Ape by Desmond Morris (1967)

This classic about humanity’s place in evolution is still a fun read, because Morris writes with such humour. We may have the biggest brain for our body size, he said, but should never forget that we also have the biggest penis. He went on to treat human sexuality as explicitly as only a biologist can. Many of his provocative ideas are now outdated, but some have withstood the test of time, even though the author is rarely credited for them. These include speculations about the link between primate grooming and human gossip, or the roots of human monogamy.

4. Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behaviour by Robert Richards (1987)

A critically important book at a time when most evolutionary writing went to the dark side. Biologists couldn’t stop talking about selfishness, competition and the lack of genuine kindness in a dog-eat-dog world. Perhaps not coincidentally, this was also the time of Reagan and Thatcher and the celebration of human greed. Since all of this was advertised as Darwinian, I was profoundly grateful for philosophers, such as Richards and Mary Midgley, who illuminated a different side of Darwin, including his views on moral evolution.

5. Passions Within Reason by Robert Frank (1988)

Frank is an economist inspired by evolutionary theory. But instead of using that theory to make the case for unfettered competition, he has always emphasised the social side of our species; our commitments, our concern for fairness, our genuinely charitable impulses. He was writing about these issues long before the modern wave of behavioural economics and our current understanding that the default mode of human interaction is actually cooperative rather than competitive.

6. Ravens in Winter by Bernd Heinrich (1989)

Reading this book one can’t help but shiver, because it is all about ravens in freezing Vermont, and an author dragging frozen carcasses up and down the mountain – and waiting days for his ravens to land near them. How do these birds communicate about the food bonanza, and whom do they tolerate close to it? We learn a great deal about corvid intelligence as well as the persistence of naturalists.

7. Naturalist by EO Wilson (1994)

I am such an admirer of Wilson and his bravery in the face of opposition! A mild-mannered southern gentleman, he was accused of being a Nazi, just because he believed that biology might tell us something about human behaviour. I could list his scientific works, but the best read is still this autobiographical one. Wilson hailed from Alabama, the state next doors to mine (I live in Atlanta, Georgia), so I can relate to the nature he describes and also his early enthusiasm for all kinds of organisms.

8. A Primate’s Memoir by Robert Sapolsky (2001)

I am always jealous of authors with English as their native language, and especially of Sapolsky who is a hilarious storyteller. He writes with such ease that you’d want to go out with him to the field. A primatologist and neuroscientist, Sapolsky spent years with wild baboons in Kenya, documenting their tense social relations and stress levels.

9. Mothers and Others by Sarah Blaffer Hrdy (2009)

The debate about human evolution often turns on violence and males, with females being the passive vessels of male reproduction. Hrdy takes exactly the opposite tack by stressing female sexuality and choice, and the it-takes-a-village cooperation with which we raise our young. Very refreshing and insightful, not only in relation to our own species, but also to the matriarchal society of bonobos.

10. We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler (2013)

It is hard to write about this novel without spoiling its plot, but let me just say that as a primatologist I enjoyed it immensely and felt that the author had done her research and/or experienced things that I can relate to.

- Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? by Frans de Waal is published by Granta, priced £14.99. It is available from the Guardian bookshop for £12.29, with free UK p&p.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion