Health

Why Does Anyone Do Yoga, Anyway?

The health benefits are very real. But few understand how it affects the mind.

Posted June 22, 2015

After my last weekend of yoga teacher training, a friend asked me at dinner, “Why do you do yoga? So you can learn to do what, headstands?”

Why do people do yoga?

More than 90% of people who come to yoga do so for physical exercise, improved health, or stress management, but for most people, their primary reason for doing yoga will change. One study found that two-thirds of yoga students and 85% of yoga teachers have a change of heart regarding why they practice yoga—most often changing to spirituality or self-actualization, a sense of fulfilling their potential. The practice of yoga offers far more than physical postures and headstands—there is self-reflection, the practice of kindness and compassion, and continued growth and awareness of yourself and others.

Yet the health benefits are very real: Yes, yoga can increase your flexibility, improve your balance, and decrease your cholesterol. A recent review in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology showed that yoga reduces the risk of heart disease as much as conventional exercise. On average, yoga participants lost five pounds, decreased their blood pressure, and lowered their low-density (“bad”) cholesterol by 12 points. There is a vast and growing body of research on how yoga improves health concerns including chronic pain, fatigue, obesity, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, weight loss, and more.

As a psychiatrist, though, I am also naturally interested in the brain. While most people intuitively get that yoga reduces depression, stress and anxiety, most people—even physicians and scientists—are typically surprised to find out that yoga changes the brain.

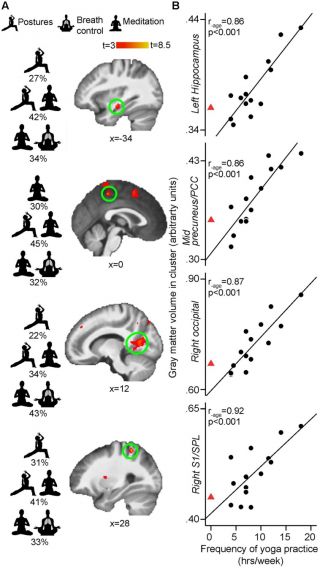

A new, May 2015 study published in the Frontiers in Human Neuroscience uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain to show that yoga protects the brain from the decline in gray matter brain volume as we age. People with more yoga experience had brain volumes on par with much younger people. [In the figure to the left, red triangles represent people who have zero yoga experience and filled circles are people who practice yoga with varying frequency]. This finding has also been true in brain imaging studies of people who meditate. In other words, yoga could protect your brain from shrinking as you get older.

Even more interesting, the protection of this gray matter brain volume is mostly in the left hemisphere, the side of your brain associated with positive emotions and experiences and parasympathetic nervous system activity—your “rest and digest” relaxation system. Emotions like joy and happiness have exclusively more activity in the left hemisphere of the brain on positive emission tomography (PET) brain scans.

But the truth is that the practice of yoga is not just about changing the brain, the body, headstands, or even about gaining greater joy or happiness. If it were, it'd be just like another spinning class or weight-training at the gym. Yoga aims toward transcendence of all those things. In a culture in which we rush from one day to the next, constantly trying to change our health, body, or emotions, or to plan the future, yoga opens up the possibility of connecting to what we already have—to who we already are.

As Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron explains:

“When we start to meditate…we often think that somehow we’re going to improve, which is a subtle aggression against who we really are.

"Meditation practice isn’t about trying to throw ourselves away and become something better. It’s about befriending who we are already. The ground of practice is you or me or whoever we are right now, just as we are. That’s what we come to know with tremendous curiosity and interest….We recognize our capacity to relax with the clarity, the space, the open-ended awareness that already exists in our minds. We experience moments of being right here that feel simple, direct, and uncluttered.”

So, why do I practice yoga? The answer can be complex and personal, but it can also be simple and universal: Because I want to be present. Because I want to be present not just on my mat but also to myself and the people—the community—around me.

Yoga can change the heart—but we’re not just talking about blood pressure.

Marlynn Wei, MD, JD is a psychiatrist and author in New York working on an upcoming yoga book with co-author Harvard psychiatrist James E. Groves, MD.

Follow me on Facebook and on Twitter @newyorkpsych

Copyright Marlynn H. Wei, MD, PLLC © 2015

Dedicated to the yoga teachers (Ossi Raveh, Be Shakti, Dennis Teston, Mikki Raveh, Allegra Romita, and many more) and fellow teachers-in-training at the Brooklyn Yoga Project—a community that befriends who we already are.

Selected References

- Park CL, et al. Why practice yoga? Practitioners' motivations for adopting and maintaining yoga practice. J Health Psychol. 2014 Jul 16. pii: 1359105314541314.

- Villemure C, et al. Neuroprotective effects of yoga practice: age-, experience-, and frequency-dependent plasticity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015; 9: 281.