It all started with a tweet:

I’m dismayed there’s been no interest from the archaeological community in this splendidly-preserved ancient site. pic.twitter.com/JgjbaJv8Jq

— Foal Papers (@foalpapers) June 22, 2015Challenge accepted.

My last blog post made the case for an archaeology of videogames, one which uses the material culture of gaming to disrupt the traditional narrative of technological progress and console wars. This would involve going beyond the games themselves, and involve the entire ecosystem of videogame culture including stuff like cartridges and arcade tokens, but also what Raiford Guins has called the geography of gaming including the spaces where videogames were encountered – the arcade, the bowling alley, the bedroom. One forgotten but crucial node in this ecosystem was the place where suburban kids fuelled the home console revolution, the space where games battled for the gamer’s attention, the arena in which the console wars were waged. This is, of course, the video rental store, where I spent as much if more time surrounded by games than in any arcade.

Like the arcade, the video rental store is generally a thing of the past, a lost landscape that now survives mainly in the memories of children of the 1970s and 80s and would be almost unimaginable to children of the 90s. But in a similar way, this dead-end of history laid the framework for our on-demand pop culture consumption today, and could benefit from archaeological study.

The rental store chain most responsible for the way we consume home media today is undoubtedly Blockbuster Video (1985-2010). With a global span that ended when it chose to ignore the Internet, Blockbuster first responded and soon began to create the demand for more, better and faster home video and videogame releases. Blockbuster Video was founded in 1985 by David Cook in Dallas, Texas. By the early 1990s, they had become a behemoth, crushing the smaller mom and pop video stores you may vaguely remember going to in the early days. At their peak in 2004, Blockbuster Video had some 9000 stores worldwide. Then Netflix happened, and despite several opportunities to join forces, Blockbuster stubbornly refused to change and in 2010 filed for bankruptcy. In 2013, the last movie ever rented at Blockbuster was, fittingly, This Is The End.

The last BLOCKBUSTER rental 11/9 Hawaii 11PM @ThisIsTheEnd #BlockbusterMemories @Sethrogen @JamesFrancoTV @JonahHill http://t.co/RsXABlqfzL

— Blockbuster (@blockbuster) November 11, 2013Looking back, it’s almost pathetically easy to be nostalgic for Blockbuster. But as with videogames and arcades, nostalgia makes for shitty, one-dimensional history. As this in-depth obituary on Grantland reminds us, going to Blockbuster was not a pleasure, but a chore foisted on us by its ruthless choke-hold on the home rental market, and no one was particularly sad to see it go. The question here, as ever on this blog, is a simple one: is Blockbuster archaeology? What would an archaeology of Blockbuster Video look like? And more importantly, what would its mission be?

***

Last Christmas I got an email from home asking whether I wanted anything from the liquidation sale of Video Avenue, the last of my childhood rental stores to close. Only at that point did I realize that despite the countless hours and dollars spent in video rental stores growing up, there is already almost no trace of them left in the second decade of the new millennium. With my brothers’ help, I set off on a hunt to see if we could find any material evidence that any of these stores had existed at home. Despite several photos of us playing games over the years, there were no family photos taken at these soulless video stores. However, we did find this photo:

Ghosts of rentals past

There’s me (second from left) and my three brothers in a happy moment one afternoon in Puerto Rico, brought together by the movies and games we’d just rented from Blockbuster. Ours was at 258 Ave Jesus T Piñero, Hato Rey, and was a local gathering place and landmark; for several years, it was also where the school bus picked us up in the morning, and where we ended up congregating on a nearly daily basis over many long summers. Rental stores, or ‘videos’ as we called them in Spanish, were such fixtures in our lives that I can trace the course of my first three decades by which rental store we frequented at the time. Before Blockbuster, people relied on everything from eccentric corner-store establishments to the equivalent of indie record stores run by film savants, like LA’s Video Archives, famous as the workplace that shaped Quentin Tarantino in the mid-1980s. Mine were the closet-sized Concordia Video, Avenida 65 de Infantería, Rio Piedras, where I remember renting Mega Man 2, and the cavernous Hato Rey Video Club on Calle Mayaguez, my second home most summers. Both disappeared without a trace eons ago, and I’m pretty sure this blog is the first and last mention of them on the entire Internet.

Not so with Blockbuster. The obvious place for an archaeologist to start is the brick-and-mortar shops themselves. Though Blockbuster may be a fading memory, not all is lost. There are actually a few remaining Blockbusters in operation, but as this article puts it, these are BINOs – Blockbusters in Name Only, as they license the store name but are run independently by the owners. While these living museums would certainly be interesting to study from an ethnographer’s point of view, there is no reconstructing the ubiquity of Blockbuster in its heyday.

The afterlife of a Blockbuster store

The vast majority of stores are still among us – with their prime retail locations in strip malls and the like, the ghosts of Blockbusters haunt the suburbs of America. Long Island newspaper Newsday even has a slider of before-and-after Blockbuster locations (see above), showing how seamlessly these locations were recast as mattress outlets and liquor stores. The real value of hunting for the stores themselves is not in their physical traces so much as the landscape context – the relationship to residential areas was always key to their existence, as Blockbuster was a primarily suburban phenomenon. The archaeology of Blockbuster is the material culture of suburban domesticity.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/loose.dtd"> <?xml encoding="UTF-8" ?>https://www.youtube.com/embed/EVbNNGuWbyo?feature=oembed

***

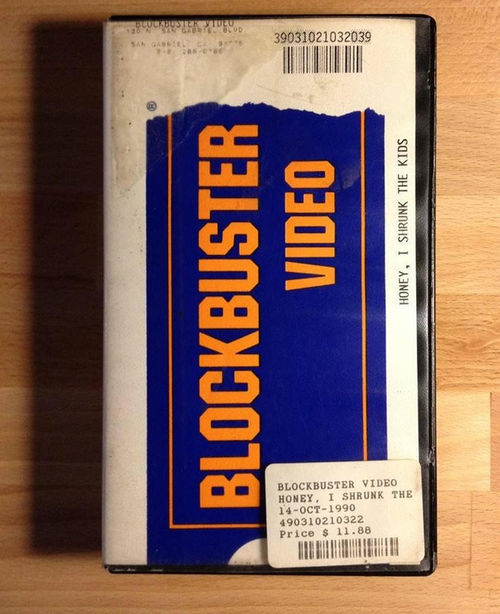

Another obvious way in which Blockbuster has entered the archaeological record is with their iconic clamshell rental boxes. These empty cases were stacked behind the movie or game when they were in stock; the customer had to take these cases to the checkout counter, where they would be filled with the desired media and bagged up like groceries to take home to feed the family. The stack of Blockbuster-branded VHS cases by the television was the sign the weekend had begun. Unfortunately, very few of these may have survived the crash unless there is an unreported Blockbuster clamshell dump in an Alamogordo landfill. The documentary of its excavation would be produced by Netflix.

The archaeology of the 20th century (source)

While the clamshell cases may be reduced to the level of eBay antiquities, there is a more exalted afterlife possible for Blockbuster. This brings us back to Blockbuster as part of the ecosystem of gaming. The decision to rent videogames as well as VHS tapes may well have changed the course of gaming history, and yet there is no mention of Blockbuster in Kent’s Ultimate History of Video Games. Nintendo of America tried unsuccessfully to stop Blockbuster renting its games in 1987, but managed to get them only on the count that some stores were photocopying instruction manuals.

After that, Blockbuster became one of the main ways to access videogames, and it was not long before they began to create demand and not just service it. There is a small subset of 90s games released exclusively through the chain. Blockbuster even rented entire consoles, and I remember with great fondness the momentous decision to rent a Super Nintendo (with Street Fighter II) for a weekend in 1992. This helped convince my sceptical parents to invest in the expensive new console in a time when NES games were not only still playable, they were still being produced as late as 1994. But it was not always able to influence demand: our local Blockbuster branch was the one and only place I ever played a Nintendo Virtual Boy, the epic failure of a virtual reality system released in 1995. Playing it in-store confirmed that neither I nor any breathing human would ever pay for such a shitty piece of shit, and its fate was sealed.

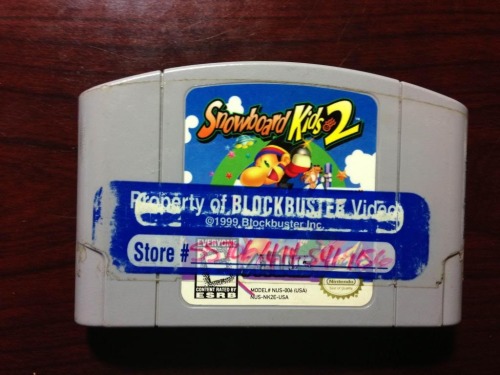

Authenticity vs aesthetics (source)

This raises a heritage management issue. Now that videogames have become antiquities proudly collected and even displayed in museums, we have the responsibility to contextualise them as much as possible to make their stories relevant beyond nostalgia. Instead of displaying games in mint condition with undamaged, original packaging, a more realistic collection might include a few games whose labels are obscured by the Dreaded Giant Blockbuster Sticker of Death. There are numerous forums dedicated to the subject of removing Blockbuster labels from games, but future museum curators should resist the temptation and proudly display these as artefacts evidencing the gaming ecosystem of which video rental stores were a key node.

Speaking of museums, it should be noted here that I know of at least one way in which Blockbuster Video has entered the excavated archaeological record and is currently displayed in a major museum. In a previous blog post, I discussed the new 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York City and the strange array of mundane material culture displayed there. Among the objects that struck me the most was a laminated Blockbuster Video membership card found in the wallet of one of the victims (below). This simple reminder of a bygone age is one of the most poignant timemarks in the entire assemblage, an artefact of the home video revolution accidentally preserved along with the name and image of the dead.

The mortuary archaeology of Blockbuster (source)

***

So what is the mission of an archaeology of Blockbuster? The material remnants of Blockbuster Video are witnesses to the transformations of suburban domesticity in the Nintendo era, when indoor kids like me were establishing the demand for movies and games to be accessible and affordable, even if only three days at a time. Blockbuster’s thousands of titles per store also made it possible for more obscure movies and games to have a longer afterlife and wider reach, and before long it may well be that the only surviving copies of these rarities are those stamped with Blockbuster labels. The history of videogames especially has a blind spot for Blockbuster, and while they may not be as evocative as arcades, rental stores are one of the great lost landscapes of gaming.

Follow us on Twitter @AlmostArch

Notes

dykekingofhell reblogged this from almostarchaeology

dykekingofhell liked this

sophisticatedwithasmile liked this

kitsunetamashii liked this

springald-jack reblogged this from almostarchaeology

kirbuu reblogged this from foalpapers

kirbuu liked this

arthurcrane liked this

icenrose liked this

bunnycartoon liked this

petro1986 reblogged this from foalpapers and added:

I know in Morecambe in Lancashire, there’s a Blockbuster Video sign still there, joining the Polo Tower (that’s still up...

mlptales liked this

foalpapers reblogged this from almostarchaeology and added:

foalpapers reblogged this from almostarchaeology and added: I was mostly kidding when I made that tweet, so I’m truly amazed and impressed by the response here. Great stuff, and...

foalpapers liked this

foalpapers liked this liatai liked this

particlequeen reblogged this from almostarchaeology

particlequeen liked this

almostarchaeology posted this