I bought my first John Fahey album around about the same time that I discovered the novels and short stories of Richard Brautigan and the two American mavericks are linked in my consciousness to this day. The album in question was The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death, originally released in 1965 in its ornately drawn gothic cover, on Fahey's own Takoma label and later reissued on Transatlantic.

It may have been the way the name evoked the mythology of an older, lost America that made me connect it in some vague way with Brautigan book titles like Trout Fishing in America, In Watermelon Sugar and A Confederate General from Big Sur.

Both Fahey and Brautigan were makers of mischief as well as myths, who played around with form and tradition. Both seemed to belong to an older era – on the Picador book cover of Trout Fishing In America, Brautigan looks like he would have been quite at home hanging with the Band at Big Pink. In many ways, they were artists in thrall to what Greil Marcus famously called "the old weird America", the traces of which remained only in folk stories and ballads, in the oldest, most primitive-sounding versions of folk, blues and country. But they were also, in their different ways, modernists negotiating their way mischievously and not altogether reverently into new forms, new languages.

As I found out much later, The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death was a title intended to confuse. Likewise the strange overblown sleeve notes - "A disgusting, degenerate, insipid young folklorist from the Croat & Isaiah Nettles Foundation for Ethnological Research meandered mesmerically midst marble mansions in Mattapon, Massachusetts …" Fahey was having his own kind of fun at the expense of blues and folk music collectors, of which, ironically, he was one. The music, though, was something else: intricate, intriguing, multi-layered, resonant. It has stayed with me ever since, becoming, over the years, a constant.

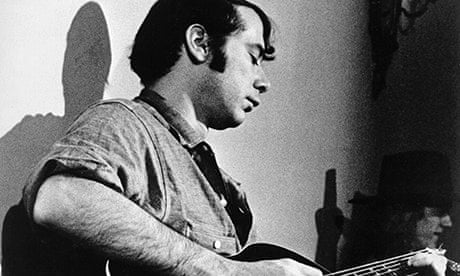

That music is, in the main, solo and acoustic, played on a steel-stringed guitar. I distinctly remember my younger self being somewhat wary of buying an entire album of acoustic guitar instrumentals, but the more I listened to The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death playing in the background as I browsed the racks of a now long-gone second-hand record shop in Camden Town, the more it cast its spell.

Reading on a mobile? Click here to watch video

In Fahey's hands, a single song can carry echoes of all the older musics he was drawn to – traditional folk ballads, blues, bluegrass, gospel, spirituals – but simultaneously sound somehow new and utterly unique. When he interprets an old song like John Henry or even Bicycle Built for Two, he reinvigorate it with the restless imagination of his playing. On Old Southern Medley, from The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death, he even lists the musicians he is evoking: the great American songwriter Stephen Foster, Fahey's beloved Charley Patton as well as Daniel Decatur Emmett, a self-taught songwriter and musician who founded the first blackface minstrel troupe in 1843.

Fahey's tastes tended towards the old and overlooked, the strange and the primitive, and his guitar playing seems to summon up the spirits of long-dead blues and ragtime pioneers. More so than anyone apart from maybe the Bob Dylan of The Basement Tapes, he is perhaps the pivotal link between the various, almost-lost folk musics of another, older America and the singers and the contemporary musicians loosely grouped under the rubric of Americana.

In a new documentary on Fahey, In Search of Blind Joe Death: The Saga of John Fahey, which has is doing the rounds of indie film festivals and will be shown by BBC4 in December, the musicologist Rob Bowman, notes: "It's hard to imagine what contemporary music would be like if people like John Fahey had not been obsessively fascinated with roots American music from the 1920s and 30s. That's the secret of a whole swathe of modern rock'n'roll. It was his sense of collage, soundscape and dissonance that influence people like [Pete] Townshend, Thurston Moore and Beck."

Perhaps surprisingly, it is Townshend who is most laudatory in his summation of Fahey, telling the film-makers: "Could I go so far as to say he is the innovator? I think yes … he is definitely worthy of the term iconoclast. He is in his own bubble." That last part is true not just of Fahey's playing, but his singular and singularly eccentric life. He was born in Takoma Park, Maryland on 28 February 1939. He bought his first guitar from Sears & Roebuck for $17, aged 14, and his first musical epiphany occurred when he heard Blind Willie Johnson's Praise God I'm Satisfied on a 78rpm vinyl recording in a friend's house.

"I started to feel nauseated so I made him take it off, but it kept going through my head so I had to hear it again," he told the music writer Edwin Pouncey, in an illuminating interview for The Wire magazine in 1998. "When he played it the second time I started to cry, it was suddenly very beautiful. It was some kind of hysterical conversion experience where in fact I had liked that kind of music all the time, but didn't want to. So, I allowed myself to like it."

Reading on a mobile? Click here to watch video

A few years later Fahey had an even more transformative encounter with the music of Charlie Patton, when he discovered a copy of High Water Everywhere. His subsequent obsession with Patton was such that he turned the blues musician into the subject of a thesis for his master's degree. That obsession led him to start mimicking the music he loved on guitar, a talent that astonished his friends and led to the recording of a 78 of blues tunes on the Fonotone label under the pseudonym Blind Thomas. So it was that, somehow fittingly, the great adventure that is John Fahey's music began in proto post-modern style with an elaborate prank.

The Blind Thomas recording was a kind of accidental blueprint for The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death and much of what would follow from it. "He was always making up the myth of John Fahey," says his ex-wife, Melody, in the documentary. "At some point, he decided he wasn't a black blues singer, but he had fun pretending he was at one time." As even a cursory glance at Fahey's discography will reveal, he was also someone who, unconsciously or otherwise, continued to make mischief at the expensive of collectors and completists. His debut album proper, 1959's Blind Joe Death, is not to be confused with the aforementioned The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (1965). And, to make matters more confusing, The Legend of Blind Joe Death, released on CD in 1996, is an extended version of the debut.

What's more, the original sleeve notes to Blind Joe Death attributed the music on one side to an obscure blues guitarist called Blind Joe Death and the other side to Fahey. In his sleeve notes to that 1996 edition, Glen Jones writes: "This was the first of many subterfuges perpetrated by Fahey, whose future liner notes (and those of aide de camp, Ed Denson), would be full of lies, in-jokes, obscure references, and absurdities, often written in a tone that mocked the texts of prominent blues scholars and folklorists of the day. Considering the fact that Fahey was then as well known as his invented blues counterpart, one wonders how many people outside Fahey's immediate circle of friends 'got' the joke (or cared), or why he bothered to perpetrate such a deception in the first place. Though the deeper answers to that question must lie in the recesses of Fahey's noggin, the fact is that John has always done exactly what he wants and has sought to amuse himself first and foremost."

The prankster element masked a deep seriousness of intent, though. Fahey was also a perfectionist who rerecorded some of his albums, including the great Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes, originally released in 1964 and then again in an "improved" version in 1967. (You can hear both versions on the 1999 CD deluxe reissue and, lo and behold, the first one sounds more timeless and mysterious.) On YouTube you can hear him play the stately In Christ There Is No East Or West in its original version from Blind Joe Death and in a much fuller live recording from 1968. You can even watch an older, grizzled Fahey play it and then try to break it down for us lesser mortals.

Reading on a mobile? Click here to watch video

For the uninitiated, The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death or Deathchants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes are perhaps the best places to start negotiating Fahey's extensive and varied output, though various compilations also provide a good survey of his style. (Blessedly, Youtube is full of Fahey, both young and old,inspired and indulgent.)

I have to admit that, after all these years, it remains something of a mystery to me what it is exactly that Fahey does that so mesmerises, despite having had it explained to me by several accomplished guitarists and Fahey enthusiasts. For me, the obvious dexterity and seemingly effortless technical brilliance of Fahey's playing is only one part of the equation of his greatness. His songs often work on me like a spell through his use of those strange tunings, his reliance on repetition, dissonance and layered melody as well as the way he constantly introduces slightly different variations on a single pattern. Put simply, his playing just draws me in every time and takes me somewhere else: a place approaching the realm of attentive daydream. (John Martyn at his most driftingly, hazily explorative does the same thing in a different way.)

"I think of myself as a classical guitar player," John Fahey once said, sounding regretful. "But I'm classified as a folk musician." For me, though, he is both and neither. His playing is just too singular to be generically labelled. On Fare Forward Voyagers, for instance, he incorporates elements of eastern raga into his already complex musical patterns and the results,one of which is extended across an entire side of the vinyl record, is even more meditative and mesmerising.

Sadly, Fahey's life, for a time at least, adhered to the kind of ill-starred trajectory of many of the neglected blues musicians he admired. When Pouncey caught up with Fahey in 1998, the musician was living in "a chaotic motel room" in Woodburn, Oregon. He had survived a long period of decline and neglect in the 80s in which he had succumbed to alcoholism and been diagnosed with diabetes. He had also contacted the rare Epstein Barr virus, which rendered him too tired to perform. Times had gotten so bad back them that he had been forced to pawn his guitars and trawl flea markets and secondhand shops for rare classical records to resell to collectors.

Worldweary and stoical, Fahey seemed dismissive of his greatest music and laid bare the deep well of sadness and despair that lay underneath the often serene compositions. "I was creating for myself an imaginary, beautiful world and pretending that I lived there, but I didn't feel beautiful,'' he told Pouncey, "I was mad but I wasn't aware of it. I was also very sad, afraid and lonely."

By then, despite everything, his fortunes had once again changed for the better. The release of a double retrospective, The Return of the Repressed, on the Rhino label in 1994, had reignited interest in is music and brought him to the attention of a younger audience, many of whom had heard his name dropped by the likes of Jim O'Rourke or Thurston Moore or and Beck. There was some poetic justice in this given that Fahey had been among the first of the independents, founding Takoma in the late 50s and releasing his own recordings and those of the overlooked musicians he liked, from fellow steel string guitar maestro Leo Kottke to one-off talents like Robbie Basho and veteran blues singers like Bukka White.

Fahey, then, was a pioneer in all sorts of ways, then, but it is his music that endures. Some of it, like the two albums he recorded for the Reprise label in the 1970s, Of Rivers and Religion and After the Ball, feature a Dixieland orchestra, and are very much an acquired taste. Likewise, for different reasons, the late works he recorded in the 90s on the Revenant label, on which he played effects-laden electric guitar and drifted into some inner zone that is hard, at times, for this devoted listener to connect with. Then again, Fahey was always impulsive and unpredictable. He once made an inspired Christmas album, The New Possibility (1969), which became a surprise hit, and the often spellbinding Fare Forward Voyager (1973) was a set of extended solo guitar meditations inspired by TS Eliot's The Four Quartets and dedicated to a Hindu guru, Swami Satchidananda. Later, Fahey admitted his short-lived immersion in Asian mysticism was precipitated by his falling in love with the swami's secretary.

John Fahey remained an explorer and an iconoclast to the end, even publishing a few volumes of semi-autobiographical writings, including the wonderfully titled How Bluegrass Music Destroyed My Life. His final album, Red Cross, was posthumously released in 2003 following his death during heart bypass surgery two years earlier, aged 61. It's a mixed bag but there are some drifting, ghostly electric pieces that are haunting, even elegiac. Since then, the Dust to Digital label have released Your Past Comes Back to Haunt You: the Fonotone Years 1958-1965, an illuminating, brilliantly annotated five-CD box set of his early work and another testament to his singular talent.

A serious prankster whose genius led him down some dark roads, John Fahey's made music without words on a six-string guitar, music so brimful of ideas and invention, so steady and sure-footed, that it seems to evoke the entire history of popular music, and yet suggest some place beyond it, a place both real and mythical, timeless and resonant. He once described his gift as a mixture of "divine inspiration and an open subconscious". It was, and remains, transportative: a whole wide world evoked though six steel strings and a teeming imagination.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion