I’m lucky enough to have been attached to a few iconic shows – Merlin, Doctor Who, Little Britain – but 20 years on, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is still the one I get stopped in the street to talk about most. It deeply affected so many people – they tell me how it eased their growing pains, how without the show they wouldn’t have been able to cope. It gave them strength. The executives who commissioned it had no idea what they were unleashing, and the impact it would have.

The network kept wanting to change the name. “Nobody is going take it seriously if it’s called Buffy.” But that was the whole point. It’s somebody called Buffy who nobody really takes seriously, but who has the fate of the world in their hands. Joss Whedon’s original concept was to take the girl in the horror movies who falls over, twists her ankle – the victim – and make her the hero. It’s clearly a feminist parable. But it went so much further. It was this extraordinary allegorical tale that lasted seven years.

Of course, this was most apparent in the way it presented the difficulties of growing up. Take the story of Buffy’s boyfriend, Angel. He’s this wonderful, caring person, but only because he’s a vampire cursed by gypsies to have a conscience. That’s enough right there. But not for Whedon. As soon as Angel finds himself in a state of ecstasy – when he finally sleeps with Buffy – he loses his soul and becomes the one night stand from hell. It’s a situation women the world over can relate to, but presented through this horrific metaphor.

And Whedon was able to almost sense what was coming in the world. The episode Earshot predicted a Columbine-style massacre before it happened and had to be moved in the schedules as a result. But in those 43 minutes, Whedon created a three-dimensional character for this would-be murderer. Jonathan was relatable, his problems and motivations felt clear – especially to that young teenage audience. Many have tried to replicate the nuance of that psychology in far grander settings, but with nowhere near the same level of success. That’s the thing – brilliant writing connects.

One is aware in this industry that executives, who are rarely creatives, feel the need to “contribute”. Notes come through, often purely about exposition, which means that the character stuff gets whittled away because, ultimately, they underestimate the audience. But it’s that stuff that people connect to, and it’s that stuff that makes entertainment cross over from the narrow demographics that executives too often focus on.

We were lucky Buffy was off the radar – nobody expected it to do anything, so we weren’t subject to their scrutiny. We did, however get a note, in season one, on Teacher’s Pet, because we weren’t allowed to show blood. We couldn’t show the green blood shooting from the severed neck of a beheaded praying mantis demon. We shot it in silhouette instead. Whedon was able to get Buffy up and running before the higher-ups took notice – and it got a huge response almost immediately. It was a lucky accident that it was at a time when online became a real voice. A community of fans built up.

And that was the real power of the show – it resonated. Not just with girls, or teenagers, but with everyone. It gave flesh, and horns, to the demons we all face in life. That was never more apparent than in the episode The Body. Whedon liked to play with the medium. An episode where nobody talks. A musical. But The Body was something else entirely. He had said a year previously that Joyce, Buffy’s mother, was going to die – serious stuff for a teenage comedy horror. He gave her a brain tumour – “here we go,” I thought. But then she recovered. He was planning much further ahead.

“She’ll have an aneurism at the end of a really light, frothy episode, and Buffy will come in and find her on the sofa,” he told me. When it finally aired, it was gut-wrenching stuff. He’d said he thought he might strip it of incidental music, to increase its intensity – and he did. It was a brilliant and extraordinarily bold choice on a mainstream, network show for “kids”. Buffy was presented with an enemy that she couldn’t fight, an enemy that everyone can relate to – the death of a loved one.

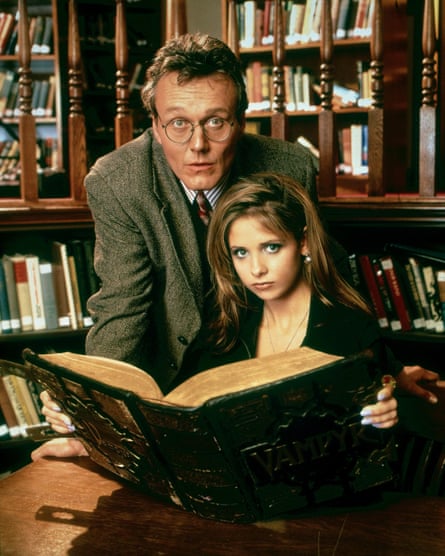

I knew Buffy was special as soon as I read the first two scripts. I was on board from the beginning. I’d come close to doing another show about demons and poltergeists and things. But it was humourless, it had no empathy, it was just in-your-face horror. My agent was telling me to take it, but my partner said wait, that something else was coming. A month later, I was in a Tex-Mex restaurant in Santa Monica on my own, laughing out loud – much to the chagrin of all the people round me who thought I was some loony Englishman. Buffy isn’t just a horror – it’s a comedy, it’s a thriller, it’s a coming-of-age drama. Whedon proved that you can have sardonic humour alongside all the serious stuff, you can turn emotions on a dime, and people love it. A laugh-out-loud moment, followed by a death. He changed television.

That’s why when a 40-year-old man comes up to me “confessing” to being a fan of the show, as if its a dirty secret, I tell him to stand proud. Buffy might have been a teenage girl, but the issues in the programme transcended age or gender. It’s undoubtedly a feminist story, about the empowerment of women, but Whedon managed to tell that story in a way that was inclusive.

He is an incredible, genius writer – so it’s hardly a surprise that few, if any, have managed to emulate that feat. Female protagonists are still thin on the ground. Executives still struggle to see how they can sell women’s stories to mixed audiences. But even if a televisual landscape filled with female heroes hasn’t followed on, there’s no doubting the impact Buffy had.

In the final season, Whedon started to build up this young group of “Slayerettes” around Buffy. I was confused. “Where is this going? Isn’t he diluting what makes the show special?” But after seven years, in the series’s final moments when Buffy handed over the mantle to all womenkind, he encapsulated the true message of the programme. And it’s that legacy that still resides in all of us, true, lifelong Buffy fans.