Scientists announced today that four women received lab-grown vaginas between 2005 and 2008 — and, according to their doctors, all of the patients are doing quite well.

The women were born with either an underdeveloped or absent vagina

The women, who were between 13 and 18 at the time of the surgery, were all born with a rare genetic condition called Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH) — a condition that causes about one in 4,500 girls to be born with either an underdeveloped or absent vagina and uterus. The traditional treatment for women with MRKH involves reconstructive surgery or painful dilation procedures. These interventions can be quite traumatic — they have a complication rate of 75 percent in pediatric patients — so researchers wanted to find a way to avoid them altogether. That's why they set out to engineer vaginas, described in a study published in The Lancet today, that would be compatible with each patient.

The vaginal organs themselves were generated using a combination of cells — epithelial cells that line body cavities, as well as muscle cells — biopsied from the women's genital areas. Anthony Atala, a urologist at Wake Forest University who conducted the trials, said in a video interview that his team took "a very small piece of tissue from the patient, less than half the size of a postage stamp, and we then teased the cells apart and grew the cells separately." The cells were then expanded and sewn onto a biodegradable scaffold that the researchers had previously shaped into a vagina tailored to each patient. Six weeks later, the women underwent surgery.

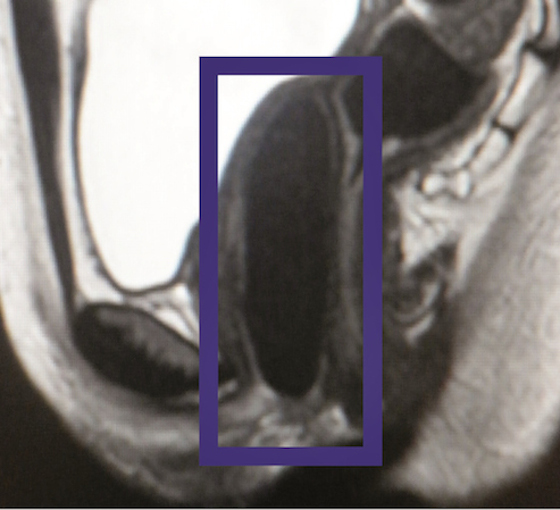

MRI image of an implanted vagina (Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine)

To implant the lab-grown vaginas, surgeons first had to create a canal in the women's pelvic areas. The surgeons then sutured the biodegradable scaffold to the patients' already existing reproductive structures. In the weeks following the operation, the women's nerves and blood vessels gradually expanded and started integrating themselves into the engineered tissue. As this was happening, the women's bodies were slowly absorbing the scaffolding. By the time the scaffolding had completely disappeared, it was no longer needed — the cells had laid down their own permanent support structure.

They can now experience pain-free sex and orgasms

Follow-up tests showed that the engineered tissue was indistinguishable from the women's native tissue. "We now show up to an 8-year follow-up with those organs showing functionality," Atala said. By "functionality," he means that the women are now able to experience sexual desire, pain-free sex, and can even reach orgasm. This operation, however, will not allow them to bear children.

Atala and his team used the same technique in 1998 to implant engineered bladders in nine children. Since then, he has also been able to implant urethras in young boys. "It was unbelievable that it could be done in a lab," said one of the women who received the treatment in a video interview. The woman, whose name has not been released, said that she hopes other girls with MRKH will hear about the treatment. "[Life] does not end knowing that you have the disease," she said, "because there is a treatment and you can have a normal life."

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/14682260/rs040714-152_hi-rez.0.1409700987.jpg)