“I’m really desperate to get out there,” says Christopher Sharp, co-founder with his wife, Suzanne, of The Rug Company, which has just added a Cape Town store to its 24 shops around the globe. He is talking about earthquake-stricken Kathmandu where the company’s carpets – by designers such as Vivienne Westwood, Kelly Wearstler, the late Eva Zeisel, BarberOsgerby and Jonathan Adler – are hand-knotted.

Christopher’s response is akin to the stranded Americans who itched to get back to the US after the Twin Towers were struck. “It’s very hard not being there. You want to see for yourself. You read the news and talk to them every day on the phone but it’s to the guys who run our production so it’s hard to know what’s happening with the weavers themselves,” he says.

The company maintains a close relationship with its Tibetan-run weaving facility, built up over the 18 years since its founding. They visit their weaving facility every six weeks, regularly send salespeople over to see how the carpets are made and have brought their production staff to the UK several times too.

Christopher credits the strength of their relationship and the Nepalese’s openness to new designs for The Rug Company’s ability to produce such a large collection of contemporary designer rugs (168 at the last count, not to mention a huge back catalogue that can be dipped into at any time, a vintage and traditional collection, and a bespoke service that makes up 30 per cent of the business).

It takes four months to make a rug.

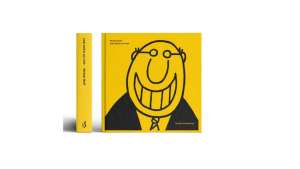

The process is recounted with a reverence to detail in The Rug Company’s beautiful book: “[H]igh on the Tibetan Plateau where the earth touches the sky, sheep living on rarefied air give up their thick oily wool to be bundled onto bulging trucks that lurch and sway as they climb through mountain passes.” You can almost hear the prayer flags flapping in the breeze.

The wool is taken to the city of Pokhara where it is washed in a Himalayan Mountain river, dried on the banks, and transported to Kathmandu to be spun, dyed and woven. It’s an ancient process Sharp doesn’t take for granted.

We’re very fortunate we can still make a handmade rug, he says.

The Rug Company prides itself on the story of its handcrafted process – and on its staff’s intimate knowledge of that process. For this luxury brand, where the rugs are made is a huge part of how they are made. The ancient art of handknotting isn’t a popular past-time in the world’s major cities, making such traditional artisanship all the more precious and giving it a certain provenance.

The Rug Company’s carpets, throws, wall-hangings and cushions may be reserved for those who can afford their premium prices but they find a market in both financial capitals and on the fringes – from Beirut to Brussels and Miami to Mexico City. Their stores there speak to the universality of what they are selling: a close connection to time-honed craft combined with considered design.

Christopher (the company’s CEO) and Suzanne (its creative director) work with fashion, product and textile designers on new ranges. Fashion designers are the easiest to work with because they turn out things quickly, he says. “They are used to doing collections, sometimes multiples in a year. And it’s about print and colour and being decisive.”

Their first fashion collection was with Italian brand Marni. “At the time Lucinda Chambers, the fashion director for British Vogue, was designing for them and she’s a friend of ours,” Christopher says. “They were taking 50s prints and oversizing them, which translated very well into rugs.”

A longstanding collaboration with Sir Paul Smith began after Christopher met him while buying a shirt in one of his shops.

When Paul Smith’s ‘Swirl’ rug first came in, I famously said it wouldn’t sell well.

“It’s now one of our best-sellers” and one of 26 different rugs by the stripe-loving Sir

Then Diane von Furstenberg approached them, which was also a hit.

“We get a lot of people sending us stuff and we always look at everything and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t,” he notes, adding that they’re in the business of collecting designs, not designers.

The Rug Company has a policy of keeping the whole collection in every shop, so it needs to constantly refine its offering every year. “We work with creative people with endless ideas so I have to very diplomatically tell them we can’t just do hundreds of designs with each. We have to mix it up.”

Suzanne, a designer herself who is obsessed with textiles, usually fills in the gaps.

The craft is what often convinces even the most difficult of designers.

I had always really wanted to work with Alexander McQueen and then I got the call from his personal assistant to ‘come and meet Lee’ (as he was known).

“She said, ‘He is difficult and often in a bad mood but take him as you find him.’ He came into the room, sat down and didn’t say anything. I thought I’m not going to talk about how much money he’s going to make or what he should design, and I wasn’t going to start complementing him and telling him how wonderful he is,” he recalls.

“I thought all I’ll do is tell him how we make our rugs: ‘We get the sheep from a high altitude. They come from the Tibetan Plateau…' I got 90 per cent of the way through explaining the process and all of a sudden he stood up and I thought ‘Oh shit’. And when he got to the door, he turned around and said ‘Yeah, we’re going to do this. This is really good’.”

For someone like him it was all about the craft. The fact that it is a beautiful craft matters to the designers we work with.

Whether or not The Rug Company will find the local market receptive is up for debate in a country where “craft” is often used as a throw-away term to describe beaded souvenirs sold at the traffic lights. But the brand is already known and admired here by those who have noticed their ads in international glossies. And as the large majority of their business is with interior designers, they hold those relationships sacrosanct and have recruited local partners entrenched in the industry to oversee their store on Bree Street.

While a company of its calibre opening in Cape Town is big news locally, it’s also a matter of keeping it in perspective. “You do it on lots of different scales depending on where you are,” says Christopher. “Our New York City shop is 4 000 square feet. Here you do it on a smaller scale.”