Are Universities Going the Way of Record Labels?

The Internet’s power to unbundle content and increase personal choice transformed the music industry—and it’s doing the same thing to higher education.

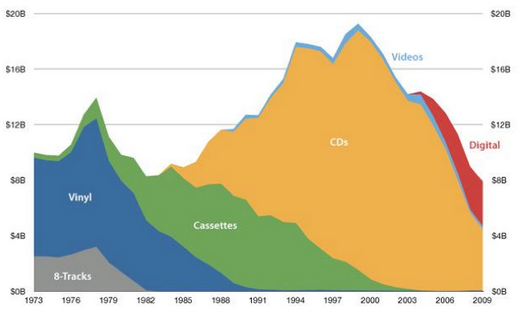

If you spent the 1990s plucking songs from a stack of cassettes to make the perfect mixtape, you probably welcomed innovations of the next decade that served your favorite albums up as individual songs, often for free. The internet’s power to unbundle content sparked a rapid transformation of the music industry, which today generates just over half of the $14 billion it did in 2000—and it’s doing the same thing to higher education.

The unbundling of albums in favor of individual songs was one of the biggest causes of the music industry’s decline. It cannibalized the revenue of record labels as 99-cent songs gained popularity over $20 albums. It also changed the way music labels had to operate in order to maintain profitability. The traditional services of labels: identifying artists; investing in them; recording, publishing, and distributing their work; and marketing them—are now increasingly offered a la carte.

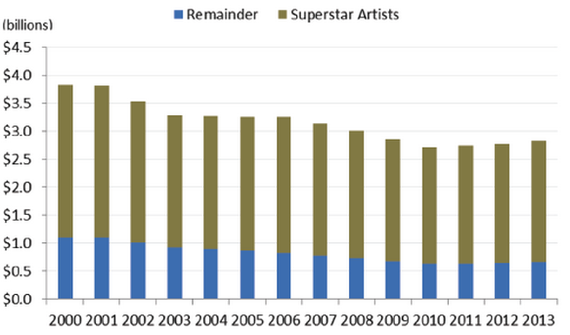

Pressure from labels then had downstream effects on content creators, specifically artists. The top one 1 per cent of artists now take home 77 per cent of revenue, and the rest is spread across an increasing number of artists. The pain of the record labels is forced on artists through smaller royalty payments.

Being a recording artist these days is a hard gig and an increasing number are going independent. Great artists now bootstrap themselves (Macklemore and Taylor Swift established their musical identities before negotiating with labels, allowing them to maintain more of the royalties).

For consumers, unbundling music is a mixed blessing. We have access to far more music than ever before, for free and on demand. But it has had an interesting effect on choice: If you step off a plane in Dubai, Dhaka, London, Dar es Salaam, New York, or Rio, much of the music is the same.

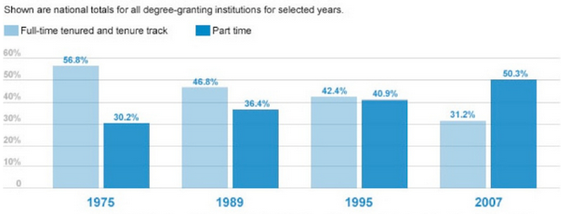

This last decade of the music industry presages the coming decade of education. Choice is expanding at every level, from pre-k to graduate school. The individual course, rather than the degree, is becoming the unit of content. And universities, the record labels of education, are facing increased pressure to unbundle their services. So what will the future of education look like?

- The price of content will freefall over the next seven years. We heard the first rumblings last year when the Supreme Court ruled that U.S. copyright owners may not stop imports and re-selling of copyrighted content legally sold abroad, paving the way for a global market for textbooks.

- The supply of learning content will swell. This might sound counterintuitive, but as we move toward a global market for content, creators will be price takers, unable to command much negotiating power given the sheer scale of distribution platforms (think iTunes). While it may make less sense for a professor in New York City to write a book, it makes a whole lot of sense for one in Mumbai.

- Education will be personalized. With learning content available on demand, students will increasingly be able to build degree programs from a wide variety of institutions offering particular courses.

- Universities will be masters of curation, working as talent agencies. They’ll draw royalties and license fees from the content professors create and curate. In many ways, the role of the best universities will become even more focused on identifying, investing in, and harvesting the returns from great talent.

Students are the big winners here. Decreased cost of content combined with increased competition among professors, and lower average ROI for universities per professor, will lead to lower tuition costs and greater choice.Great professors with interdisciplinary knowledge—the great curators—will see license and royalty fees go up as they command economies of scale in distribution. Existing institutions with large endowments will become the record labels: platforms that invest in great talent. And distribution platforms that curate content will do well, commanding both economies of scale and scope.

Meanwhile, average professors will find their incomes shrinking and their job insecurity growing. The ranks of professors will quickly diverge into the 1% and everyone else. Second tier institutions that cannot invest in talent or great content will find it harder to cover operating costs given downward pressure on tuition pricing. Those without endowments must change dramatically or go out of business. For-profit, publicly traded universities will be squeezed between increased student expectations and declining revenue; they may increasingly compete as content creators against some of today’s large publishers.

In education, a cohort of new entrepreneurs and existing institutions will greatly increase personal choice for all of us. Amidst this creative destruction, we must now ensure that in the pursuit of freedom of choice, we don’t risk hegemony of thought.