Beyond the apples: Cézanne Portraits

I have never found an artist better able to reflect the earthy, softly glowing light of a landscape as well as Paul Cézanne captured his native Provence. Whether it be his landscapes of L’Estaque or his obsessive interpretations of the Mont St Victoire, Cézanne’s landscapes breathe and quiver with the the warmth and vivacity of Aix. With their strident, vibrating brushstrokes, Cézanne perfectly replicates the quavering undulations of heated air rising from the dusty ground. And in his palette of earthy tones, Cézanne immortalises the ochre glow which characterises the villages and Mediterranean habitat of his homeland. Even Cézanne’s famous still lives of oranges and apples are characterised by the same Provencal light, and his paintings of peasants playing cards are tinged with a sense of poverty but not without the hope which the light of the Mediterranean climate always provides.

However the one aspect of Cézanne’s oeuvre which often goes overlooked is his portraiture. It’s not a genre which is synonymous with the artist – the man charged with being the father of modern art – who is better known for his first dabbles into cubist forms and semi-abstract expressionism. Yet as the new exhibition just opened at London’s National Portrait Gallery shows to stunning effect, he was truly a master of the portrait.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress, 1888-90

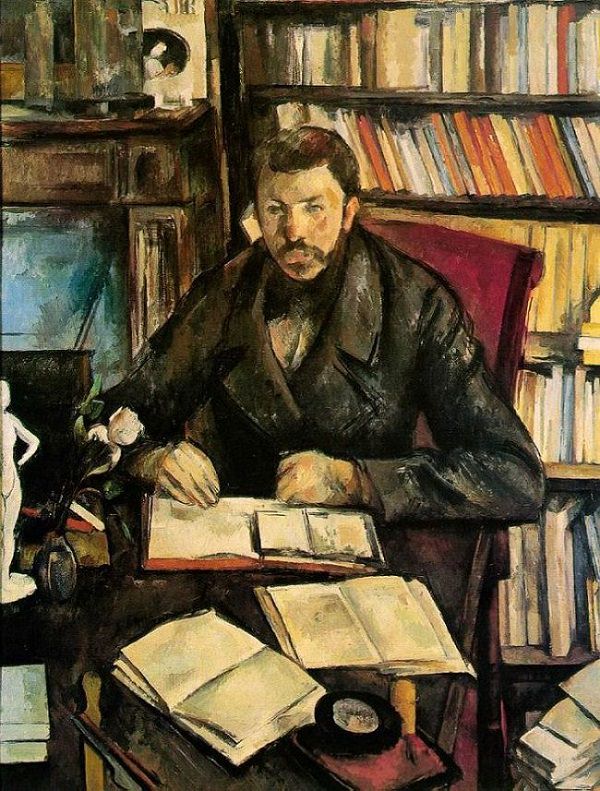

Gustave Geffroy, 1895-6

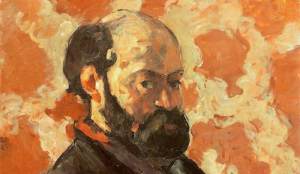

Self Portrait Rose Ground, 1875

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair, 1877

His virtuosity of the medium is manifold. First it is the intensity of character which he captures in often coarsely applied brush strokes and thickly layered paint – the brilliant portraits of his Uncle Dominique painted with only a palette knife being one such example. Through a mastery of light and shadow, and a multi-tonal handling of colour to represent the contours of skin and the movement of fabric, Cézanne’s sitters have a depth not just of tone but personality too, as his portraits emerge from the canvas as wholly realised individuals. Secondly, Cézanne’s skill resides in that same innate understanding of composition which make all of his works – even the most simple still life – such works of brilliance. For in constructing his portraits, Cézanne’s sitter is but one part of a perfectly balanced whole. Every daub of colour, every angle of sitter and background is fantastically conceived to create a harmonious balance. The result is a portrait which is deeply satisfying to behold, and which touches its audience for reasons which many will be quite unaware.

Self Portrait in a white bonnet, 1881-2

Boy in a Red Waistcoat, 1888-9

Uncle Dominique in Smock and Blue Cap,1866-7

Seated Woman in Blue, 1904

While my regular strolls into the wonderful Courtauld Gallery (happily located so close to my work) have introduced me to the world of Cézanne portraiture before, I had no idea of the scale and prolific mastery with which Cézanne meddled in the medium. With works spanning his entire career including some 26 portraits which demonstrate the same level of self-examinatory intensity as was previously mastered only by the likes of Rembrandt, the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition offers fans of Cézanne a truly unique opportunity to understand a crucial aspect of the artist’s genius. His mastery over fruit and landscapes is undisputed and well documented. But now, happily, this impossibly important third genre sees the light of day, and marks a further reason for attributing Cézanne as the true father of all modern art.

Cézanne Portraits is on at the National Portrait Gallery, London until 11 February 2018