So you’ve heard of Alessandro Scarlatti? Vaguely perhaps. Didn’t he write some rather good keyboard sonatas? Well, actually no: that was his son, Domenico. There are two Scarlattis, and given not many people have heard of even one of them, you’d be forgiven for thinking that this composer is off the beaten track because it’s not really worth the effort. So it falls to me to convince you that Alessandro Scarlatti is not only worth the effort but actually rather good.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Like many singers, I first came across Scarlatti as a student. A teacher recommended I try one of his more florid arias (Ergiti, amor) as something a bit different from the usual competition fare. I really liked it, and thought then that there must be more to this composer.

Most singers come across him in books of Arie Antiche (Old Songs) when learning to sing, and his arias are regularly murdered by well-meaning, reedy voiced wannabe singers at music festivals. There’s nothing wrong with that, but we never hear these arias as they were originally written, with an orchestra and a professional singer. So, a few years ago I started researching his music.

At Westminster Music Library I got out every score of Scarlatti’s music I could find. Conductor Laurence Cummings and I ploughed through any remotely promising arias and made a longlist, then a shortlist, my hope being to record a CD of these neglected works. I also listened to anything I could find online, including bits of a recording of Joan Sutherland singing some arias from Mitridate Eupatore, arranged very fashionably for the time (but rather inauthentically) for a larger orchestra.

Scarlatti is considered the father of the Neapolitan school of opera, and yet this early 18th-century work, possibly his masterpiece, remains unserved by a modern recording. Finding the manuscript was a nightmare – there’s a librarian in Seattle to whom I owe at least a large beer and probably dinner – but we were able to record three arias from this astonishing tale of blood, gore and clothes-swapping. To think that in 1707 Scarlatti could write the tortured chromaticism of Cara tomba is mind-boggling.

Good news: I can sing 88 notes without a breath! Bad news: Scarlatti wrote 89

And then there was Torbido irato, written for the 17-year-old Farinelli. I found a published (hooray!) score in the library and a manuscript (double hooray!) at the Royal College of Music. The music is outrageously hard, with lots of coloratura (very fast runs of lots of notes), the most mind-bending of which produced one of my best ever tweets: “Good news: I can sing 88 notes without a breath! Bad news: Scarlatti wrote 89.”

Farinelli clearly had a good set of lungs on him (castrati were renowned for this), so I resorted to using a candle flame to show my breath control (if the flame in front of your mouth flickers there is too much breath – an old castrati trick), acres of practice (my long-suffering neighbours can probably still hum this run) and an overdose of sheer bloody-mindedness to get through it. In the end, I added a few extra notes when it came to the recording, just to show off.

One of the best pieces by Scarlatti is his cantata Sul le sponde del Tebro, for soprano and trumpet. His cantatas are probably among the most recorded of his works, so I looked into other repertoire. It turns out he had a penchant for this combination (very fashionable at the time), and I found a few corkers. To create extra interest I added percussion to a couple.

This is where baroque music is so exciting. There is so much that we don’t know, and so much that was left to performers to interpret. Percussion is a known unknown – we know it was used more often than stated in the score, but not quite in which way, so you can introduce instruments with a vague stamp of authority. I felt Con voce festiva was crying out for tambourine, so we ask our percussionist to bring one. I was delighted when he turned up with not one but a boxful for Laurence and me to choose from. Early music has a lot to offer anyone inclined to geekiness.

Laurence Cummings and I spent many hours together dreaming up spectacular things for me to get my tonsils around

Finding a record label willing to let me commit a selection of my discoveries to disc was a huge bonus. Thank you, Harmonia Mundi USA. Another big help was the Borletti-Buitoni trust, which supports interesting projects.

Then there was Laurence Cummings. As well as expertly curating my ideas and weeding out some of the more bizarre ones, he also helped with the extra ornamentation so essential to this style. Scarlatti Sr pretty much invented the da capo aria. Da capo means “from the top”, the instruction to go back to the beginning and sing the first section again once you have sung the two written-out sections of the aria. But, rather than sing the first bit the way you did before, you improvise, adding notes and different lines. Laurence and I spent many hours dreaming up spectacular things for me to get my tonsils around.

It’s been a major undertaking to put all this music together for the disc, to find the scores and to learn 16 technically difficult arias, many of them da capo. Along with the music for Farinelli, gems from Mitridate Eupatore, dazzling trumpet wizardry, frankly crackers ornamentation and tambourine fun are Io non son, an aria with words by a pope, Figlio, tiranno!, from an opera written for five castrati and a tenor (just imagine the dressing-room tension), Mentr’io godo, a piece my husband simply refers to as the “sexy times” aria, plus other fabulous tunes. The disc puts together the various facets of a neglected composer and showcases his inventiveness and diversity in a broad portrait.

And for my next trick? Well, I am dreaming up another disc of course, now the five years working on this project are over. The contents are top secret for now, but I have a title. I think it’s going to be called MegaWatts…

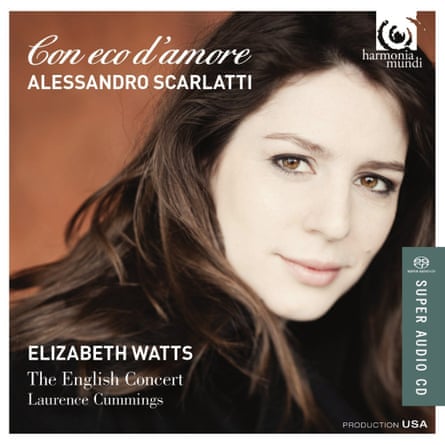

Con eco d’amore, recorded with the English Concert and Laurence Cummings for Harmonia Mundi, is out now. Download it on iTunes or order on Amazon. Read a review here.

- 27/11/15: An editing error meant that the phrase “Scarlatti is considered the father of the Neapolitan school of opera” became “Scarlatti is considered the father of modern opera”. This has now been corrected.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion