Going West: The World of Live Action, Competitive Oregon Trail

From epic real-life struggle, to computer game, to slightly less epic real-life struggle.

On a sunny Saturday last week, I found myself pushing a 200 pound man on an ancient kiddie wagon with two missing wheels up a hill with about a 40 percent incline while he shouted out facts about how to preserve meat. The sun beat down on us as we maneuvered him from a shady spot next to a historic wooden mill in Salem, Oregon, to the steps of the Pleasant Grove Church, an 1848 sanctuary for travelers who survived the Oregon Trail.

For me, it was a digital flashback of sorts: “You have killed a bison, but you can only carry 200 pounds of meat with you.”

Sound familiar? If you grew up in the 80’s, you might remember the line. It’s from the Oregon Trail—a beloved computer game that, on this particular Saturday, I was playing again. Only this time it wasn’t on the computer, it was in real life.

My first trip down the Oregon Trail took place in an elementary school computer lab in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, just a few miles from where pioneers built the first Conestoga wagon. I pounded out decisions on how to travel pioneer-era America safely from Independence, Missouri, to the Oregon Country on a green-screened computer game for the Apple II. I must have died at least 37 times before finally seeing my family of pixilated settlers safe at a homestead in the Willamette Valley.

For the generation of Americans who grew up in the 1980s, this game, designed by Don Rawitsch of the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium in 1978, was the ultimate in American odysseys—a road trip story of worst-case scenarios that taught us the pleasures of surviving everything a tough, cold world throws can throw at you. Now, that generation has grown up, and they’re not ready to give up on the Oregon Trail.

Adults today, with real resources and skills and perhaps even a measure of success in the game behind them, are taking the nostalgic computer game, and turning it into a live action, role-playing, full contact game. I’m one of them, and I came to win.

Rawitsch was a student teacher in a middle school history class in Minnesota when his supervisor charged him with coming up with his own lesson plans about the great American Western migration. Few classrooms had computers at the time and the personal computer didn’t even exist. Rawitsch envisioned a board game where players would travel across a map of the United States, but after a conversation with his roommates—two mathematics majors—he created a barebones computer program for a teletype device with a dial-up connection. “There was no precedent for computer games, nothing to admire or to look to for inspiration,” Rawitsch told me.

A few years later, after reading several diaries of trail survivors, Rawitsch took the game code to the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium and began incorporating the narratives and statistical realities of real settlers into the game’s interface. Things in the game happened not at random, but based on the actual historical probability of it happening. “When you lose oxen in the game, it is based on the historical record and the probability of that occurring at that point on the actual trail,” Rawitsch said.

In some ways, Oregon Trail was the antidote to the self-esteem movement that was raging at the time. The game didn’t care how we felt about ourselves. There was no time to gauge your feelings when your wagon just broke apart in the Platte River. When your kid just died from cholera, you didn’t check in with each other, you just kept your wagon train a-moving.

In the decades since, the game has allowed users to experience one of America’s great mass migrations—over 200,000 made the grueling trek to the land they called "Oregon Country" in the mid-1800s—through a sometimes unintentionally funny simulation. Beginning with pixelated green-on-black graphics and moving later to today’s realistic, color versions of pioneer life for the iPhone, the game has taught two generations of Americans the rewards of planning ahead, perseverance, survival, and patience while planting in their minds a compelling story of leaving it all behind in search of greener pastures. “It was the first computer game most people remember where they were dropped into the story of the game and became part of the experience,” Rawistch said.

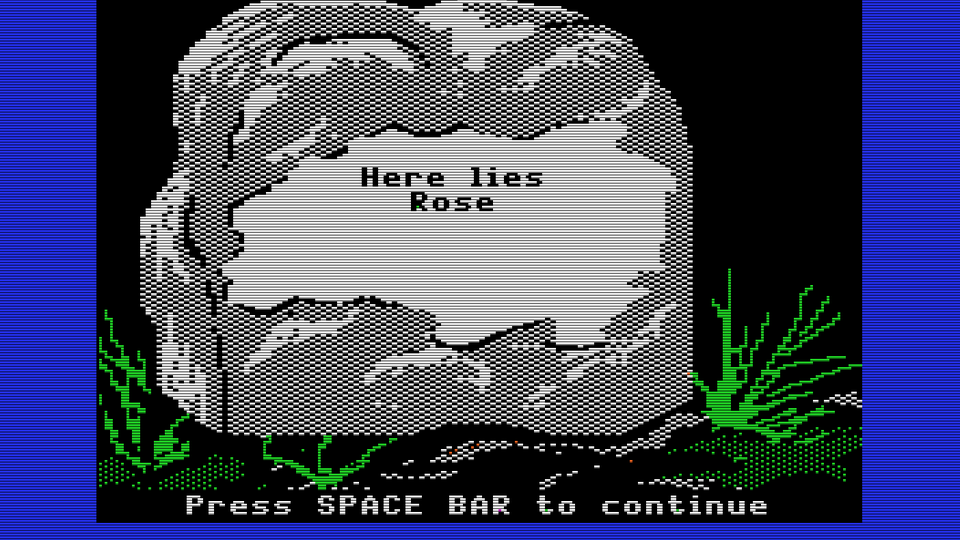

Caulk your wagon. One of your oxen has died. You are only able to carry 200 pounds of meat. You have died of dysentery. Press spacebar to continue. Compared to the hurly-burly fantasia of contemporary video games, the pixilated challenges of the early-version Oregon Trail may seem beyond twee. But at the time, the game proved nothing less than revolutionary for making history accessible to children.

“In the 1970s, you shoved information into kids’ heads and hoped it stuck,” said Kathleen Schulte, education coordinator for the Willamette Heritage Center. “The Oregon Trail gave children a measure of control in their learning and did it in a memorable way.”

Fast forward to 2012, when Kelly Williams Brown, a writer who would later pen the book Adulting: How to Become a Grown-up in 468 Easy(ish) Steps, came up with the idea to take Oregon Trail and subject live bodies to it. “If you’ve played the game you realize how shockingly boring it was,” says Brown. A reporter for the Statesman-Journal in Salem at the time, Brown noticed that two generations within her newsroom had some experience of the game. “It has all of these touchstones that have made it into the culture. We thought: Someone has to do this.”

Brown approached The Willamette Heritage Center, who was quickly on board, seeing in a live-action Oregon Trail a chance to capture the attention of two hard-to-reach audiences for historic museums: young families and young adults. So for the past three years, the live version of the game has taken place in Salem, Oregon, a historic destination for many settlers who came to the Willamette Valley.

Here’s how it works: Teams of 2-4 people, many in pioneer garb, build a wagon out of paper and dowel rods before tackling ten challenges inspired by the computer game—things like floating the wagon across a kiddie pool, shooting at game with nerf guns, competing in a three-legged dysentery race to an outhouse. Instead of finding shelter, we built a tarp tent while volunteers sprayed us with water. We survived being pummeled with pool noodles by roller derby girls at the Platte River station.

After each challenge, every team gets a colored star based on how well they perform: One gold star means your team thrived, silver means you survived, but just barely, and a red star meant you probably perished, but you completed the station. A homesteading exam at the end tests knowledge of trail trivia from signs posted throughout the heritage center campus.

If the computer game’s educational take-away was a lesson about anticipating tragedies, then consider me educated. In the weeks before the event, I invited my most trail-worthy friends to join me—a team with true grit. We called ourselves The Pixelated Pioneers: Ian Johnson, a historian for the State of Oregon, John Pouley, assistant archaeologist for the State of Oregon, and Nicole Bettinardi, a geologist turned stay-at-home mom. In an ironic twist, we lost someone from our wagon before the day even began—my best friend Stephanie, a poet, succumbed to the common cold.

At every turn the live action game converts the computerized saga into a real life obstacle. Die on the real trail—and 50 percent of travelers did in the trail’s its first years—and you’re good ole dead. Perish in the computer game—of dysentery, cannibalism, drowning, cholera, typhoid, measles, or snakebite—and you get to see your own epitaph. Kick it in the live-action game and your friends must compose a dirge to sing at your funeral. In our case, we composed a dirge for our ill-fated fifth member, with Stephanie represented by a Justin Bieber paper doll I made that morning.

“Alas, poor Bieber, we knew him so well,

we’ll be happy to see him someday, in … heaven!”

Our other tasks drew on the major moments of the computer game, an Oregon Trail twice removed. As I predicted, each of my team members brought something real to our journey. Nicole engineered a balloon engine to propel our wagon across a tiny swimming pool. John’s leadership hastened us to victory in the three-legged dysentery race to an outhouse. Both historians brought it in the homestead quiz testing our knowledge of Trail Trivia (they even corrected some of the trivia questions).

I’m a writer. In the Tall Tale Challenge we were given a list of historical trail setbacks and charged with telling an exaggerated yarn about it. I told a very tall tale indeed, about a pop star so charismatic he got a grizzly bear to lay down in front of him like a rug with a simple toss of his hair.

And then there was the problem of meat. On the trail, as in the game, if you killed a bison, you could only carry 200 pounds of meat with you. In the live-action game, participants face the task of pushing 200 pounds of meat up a hill—in this case, a 200 pound man in a wagon regaling the crowd with meat facts. In our case, it was a local butcher dressed like a cow, who later tested us on the names of cuts of a side of beef.

I could complain about the 85 degree heat or the poor technology, but the real Oregon Trail was something of a train wreck before train wrecks. The one thing that didn’t wreck, however, was our man in the cart: “You guys didn’t get all the facts right, but that’s the safest I’ve felt getting pushed up the hill, so … you get a Gold Star!”

At the end of the trail, three hours, eight gold and two silver stars later, we signed our homesteading documents with a quill pen and established a tiny 4’x4’ homestead in the shadow of Mission Mill, complete with miniature log cabin, grazing pasture, river access and a field of winter wheat.

“So what’s it like to be married to be the winner of the golden cowbell?” I asked my husband when I got home that night.

We had bested the other 20-odd teams by a hair, winning, in the end, when Nicole destroyed a bonneted settler in the tie-breaking lady arm-wrestling match.

I had the glassy-eyed self-satisfaction of anybody whose body and mind had been put through the wringer on a long journey, albeit one that took three hours and had a hot-dog stand within view. And in the end, I had but one regret: that I had left my husband and two kids at home.

More than half of the pioneer teams tackling the trail that day were families, with parents who grew up with the game driven by their nostalgia and a struck with the desire to have their kids feel real life outside the digital space. The Oregon Trial Live, in that sense, is a natural outgrowth of culture for my generation—adults who grew up glued to the game, but who now monitor their kids’ screen time and actively engineer hands-on activities as a method to learning. Rawitsch took a real life challenge and put it on the screen, to teach kids about history in a format that was totally new at the time. Now adults are wrenching that game back off the screen, to teach kids about history in a way that some have forgotten.

The nostalgia is intense, the group bonding quotient is high, the survival rate is through the roof. And luckily, the chances of dying of dysentery? Next to none.