Kiya Gezahegne joined an unruly, jostling throng surrounding a priest who wielded a 12th-century gold and bronze cross, one of the most sacred artefacts in Ethiopia. A young man shut his eyes and trembled from head to toe as he was blessed. Finally, Gezahegne stepped forward and stooped so the priest could tap the cross all over her body. "I felt close to God," she said.

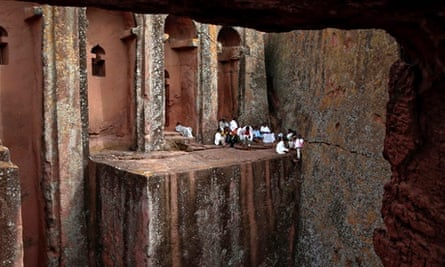

Steeped in ancient ritual, this was the scene revealed by dawn's first light in the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela. The cool morning air was filled with the smell of incense and the drumbeat and chanting of hundreds of pilgrims swathed in white robes, some kissing the walls. A sprinkling of foreign visitors groped through narrow crevices and labyrinthine tunnels. Earlier this year they included George W Bush and family and Evgeny Lebedev, the newspaper proprietor.

Lalibela – described by Hilary Bradt, the travel guide author, as "the number one sight in Ethiopia and perhaps the most astonishing man-made site in sub-Saharan Africa" – is crucial to a drive by officials to banish images of famine and conflict, and turn the east African country into a fashionable destination. A "tourism master plan" is being finalised to boost visitor numbers, which are already growing by 10% a year.

Gezahegne, 22, an academic at Addis Ababa University, was making her first pilgrimage to Lalibela one recent Sunday and was in no doubt about its potential to attract Christians and non-believers alike. "Most people know about the famine but not the historic sites," she said. "If the tourism bureau can advertise it, it can be a good source of income."

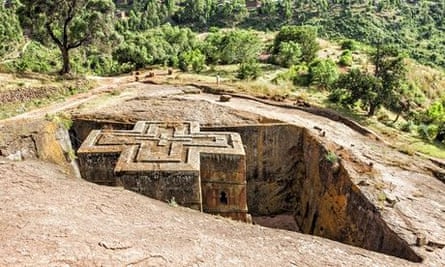

The 11 Ethiopian Orthodox churches here have to be seen – and walked through – to be believed. They were built in the 13th century on the orders of King Lalibela, not from the ground up but chiselled out of the town's red volcanic rock hills. Legend has it that the toil of thousands of labourers on this "new Jerusalem" during the day was continued by angels at night.

The last church to be completed, the Bet Giyorgis, or Church of St George, is shaped like a cross, freestanding inside a deep pit, so to reach the entrance visitors must climb down awkward, crowded stone steps. Inside, among the bibles, candles and holy water, there are intricate carvings and reliefs of exquisite detail.

The churches were included in Unesco's original world heritage list in 1978 – then an elite group of only 12 sites, which has since grown to nearly 1,000. They seem ripe for the international tourist trail.

J J Reidy, a 26-year-old student from New York, was among the recent visitors. "It's pretty amazing, not like anything you see on earth," he said. "The fact that they are carved out of rock – I've never seen anything like that."

Mary Beech, 22, a student from Washington, added: "They're beautiful. It's impossible to think about the labouring and skills necessary to create something of that calibre at that period of time."

Aurelien Francois, 30, a car designer from France, said: "It's very impressive. It's the first time I've seen buildings achieved in such a way. I've seen many cathedrals in Europe, but nothing compares to this."

In anticipation of a tourist surge, the Lal Hotel Lalibela last year added a new main building and extra rooms. Its manager, Roberto Montemar, reported an increase in visitors from France, Germany, Spain and the UK, as well as Ethiopians returning home. Some are on a religious pilgrimage.

"If you go inside one of the churches here you can feel it, like an energy coming out and touching you," he said. "It goes beyond comprehension how they were able to do it when they did it, the detail they put into them."

But not everyone expects to see the benefits. Entrance tickets cost $50 (£30), with most of the revenue going to pay more than 800 church officials, including priests, deacons and chanters. Abi Yohannes, a 17-year-old student, said: "People here are poor. The deacon and priest get a salary, but they don't help the people."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion