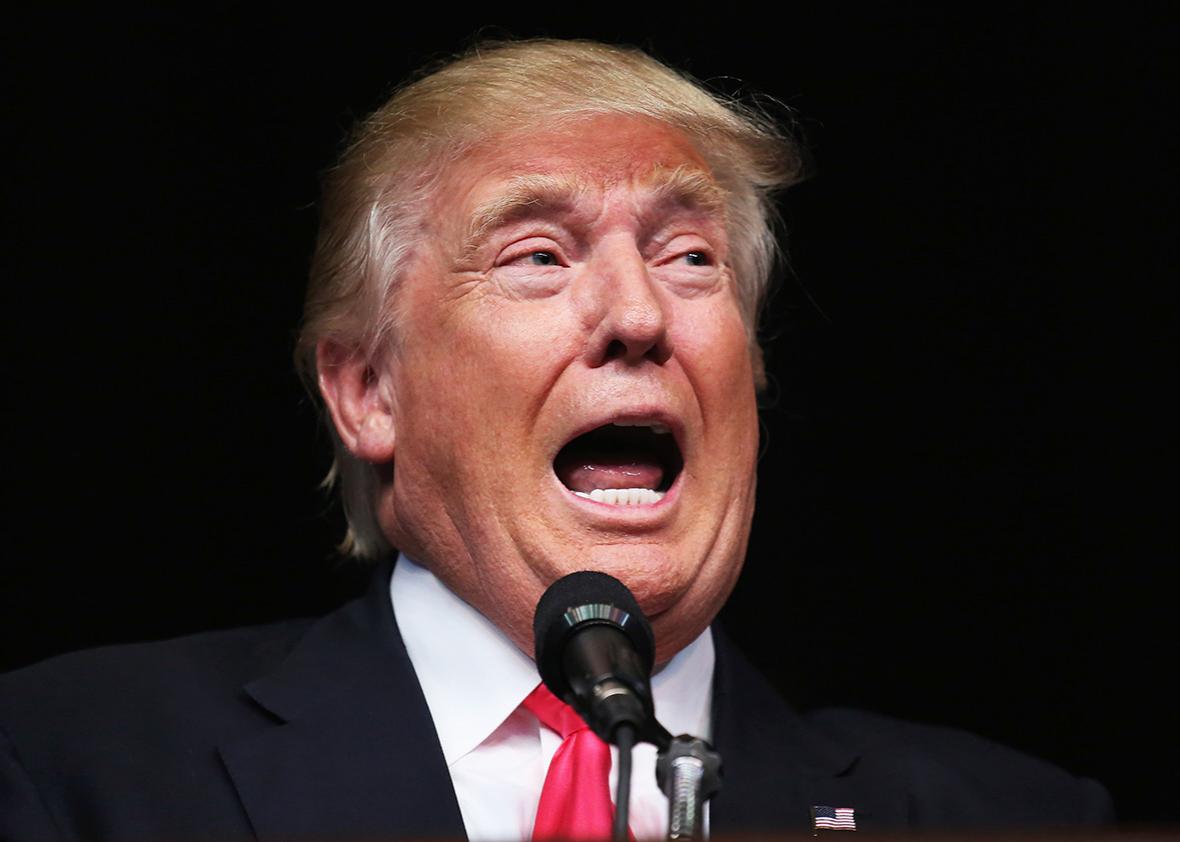

Imagine if Donald Trump’s foreign policy ideas were uttered in a saner tone by someone who seemed to have a little bit of knowledge about global politics. Would his ideas sound quite so dangerous? Maybe not, but they’d still be dangerous enough. In fact, they’d qualify as the most dangerous, disruptive, self-destructive ideas that any major party’s nominee has peddled in any living American’s memory.

These are the hardest times since the end of World War II for an American president to set and manage foreign policy. From 1945–91, the rules of the game were fairly clear: It was the U.S. versus the USSR, and power was measured by the relative stockpiles of weapons they would need in a conflict. Most of the wars fought by smaller nations were viewed (sometimes misleadingly) in terms of their impact on the East–West balance.

When the Cold War imploded, so did the entire system of international relations it had spawned. Power blocs dissolved; the subjects and allies in each now-shattered sphere of influence were free to pursue their own interests without regard to the former superpowers’ wishes. In the Middle East, Cold War politics had propped up artificial borders and oppressive regimes that otherwise would have collapsed a decade or so after World War II, along with the whole string of French and British colonies. When the Cold War ended, this collapse resumed—triggering the chaos in the region today.

In one of those ironies common to history, America won the Cold War but emerged from it weaker, not stronger. President George W. Bush’s strategic error lay in failing to grasp this fact. He, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld thought they’d entered a “uni-polar” era with the United States reigning as “the sole superpower,” able to impose its will with little effort or the need for pesky allies. They didn’t realize that the old tokens of power (tanks, missiles, atom bombs) and the old devices of leverage (Do what we ask or succumb to the Soviet bear) had lost much of their former potency and that, as a result, allies—and compromising with them on strategic goals—were now not just useful but necessary.

Bush’s father, George H.W. Bush, understood this even at the dawn of the new era. Hence his fervent campaign to preserve the vast alliance against Saddam Hussein during the 1990–91 Gulf War and his call for a cease-fire when the mission binding the alliance—ousting Iraq’s invasion forces from Kuwait—was complete. This awareness also informed the elder Bush’s decision not to rub America’s Cold War victory in Russia’s face.

Barack Obama, from early on in his presidency, understood very clearly these limits of power, the need for alliances, and the distinctions between interests and vital interests (and the levels of commitment that they justified) in this new multi-polar (or, in some ways, nonpolar) era.

Hillary Clinton understands these things as well, though she might be less resistant than Obama to using military force; some who have worked with her say she hasn’t internalized the lessons of Vietnam, Iraq, and Libya to the same degree. But her experiences have taught her that, in this new era, nations with common interests in one realm often have opposing interests in other realms, and the job of a top diplomat or president is to navigate these shoals without surrender or collision. (In some ways, this is nothing new: The United States and the Soviet Union practiced diplomacy and signed treaties, without ever dropping guard on the East-West German border, through all but the tensest years of the Cold War.)

Donald Trump, on the other hand, grasps none of these things—not the history, not the concepts, not the tools or limits or creative possibilities of power. He is not so much an isolationist as a unilateralist. It’s easy to envision him barging into a foreign war, driven as much by avenging some personal slight as pursuing a national interest—and, in the process, waving off help from others, believing that he can win alone (or that he alone can win) with the right combination of firepower and rhetoric.

Even if he didn’t start a war, or escalate one with no notion of how to end it, he is likely—judging from what he says—to wreck the few remnants of the post–World War II order that sustain America’s influence and its broad network of (mostly) democratic allies.

When the Cold War’s demise gave smaller powers the license to go their own way and follow their own interests, several of them eventually decided to remain in the American camp. This was particularly true in East Asia, after China started flexing its naval muscle, and in Europe (especially among the more recent NATO members of Eastern and central Europe), after Vladimir Putin started living his dream of restoring the old empire out loud (or at least trying).

Trump says he wants to blow up the whole edifice. He mistakes the mutual benefits of NATO for a strictly monetary transaction, telling allies that he’d pull out America’s troops—and cancel the country’s obligation to come to their defense in the event of armed aggression—unless they paid up their fair share, as he defined it. He issued this threat in response to a question about whether he’d defend the tiny Baltic states—which Putin could invade with little trouble if physical force were all that mattered and he had no worries of a Western response. In a later interview, Trump went further and said he might bring the American troops home as a first step, predicting that the Europeans would beg him to send them back, promising to pay the U.S. as much as he wants them to pay. “You always have to be prepared to walk away,” he explained, as if he were discussing a contract dispute or a real-estate deal (which is how he seems to view all relationships), not a trusted alliance based on a 67-year-old treaty that recent events have made newly relevant.

He has issued similar warnings about what he sees as meager payments from Japan and South Korea. When CNN’s Jake Tapper suggested that a U.S. withdrawal might compel those countries to build their own nuclear weapons, as the only way to deter North Korean aggression, Trump shrugged and said “maybe we would be better off” if all three of those countries had nukes.

Trump doesn’t understand the consequences of even talking like this; he doesn’t understand the messages he’s sending to all sides. He doesn’t understand that Putin in particular must be agog at his potential good fortune. A man who might be the next president of the United States—quite aside from the fact that some of his aides have ties to Russia—has all but invited Putin to invade Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania. This impression must have been confirmed when Trump said he accepted Russia’s annexation of Crimea as a done deal and possibly a desirable one, as he’s been told that many of the island’s residents consider themselves Russian, not Ukrainian.*

No American president would, or should, go to war with Russia over the Crimea or even Ukraine. George W. Bush recognized this when he ruled against offering Ukraine NATO membership. And many people in Crimea do regard themselves as Russian. (It was part of Russia until Nikita Khrushchev gave it to Ukraine in 1954 at a time when both republics were part of the Soviet Union, and the distinction was thus fairly meaningless.) But it’s one thing to acknowledge these facts and quite another to accept with indifference a violent breach of long-standing borders. Acceding to a forcible annexation without objections, or a negotiated settlement, or even a trade of some sort (a deal), is to invite other violent breaches—and to announce to friend and foe that all borders, treaties, obligations, and alliances are moot.

Here are a few of the things that would likely happen within days if Trump were elected. South Korea and Japan, as he concedes with a shrug, would start work at once on an atomic bomb (they certainly have the technology and resources), setting off a nuclear arms race and the possibility of catastrophic crises in northeast Asia. The web of sanctions against Russia, which Obama has woven with Western European leaders in response to the Crimean grab, would collapse. Ukraine’s political leaders, who still aspire to an affiliation with the European Union, would likely cut the best deal they can get from Moscow—as would the smaller NATO nations (including the Baltics) once they realize that the other large Western European powers can do little to ensure their security without American leadership.

This is another irony of history: In his articulation of American power’s limits, Obama has highlighted those as vital interests that warrant an unbridled commitment of the nation’s power. His erasure of the “red line” in Syria did have an impact on U.S. credibility in the Middle East—but little effect on U.S. standing in Europe or East Asia. Trump often lambasts President Obama for signaling weakness in the red-line episode; but Trump is now proclaiming that, in his presidency, there would be no red line in Europe or East Asia, short of one purchased with cold cash—a transaction subject to continual review and revision, like the terms of an adjustable-rate mortgage. And yet, Trump somehow thinks his words beam a signal of awesome strength.

In the Middle East, where the Cold War’s demise has wreaked the most calamitous damage, Hillary Clinton has few compelling ideas beyond doing what Obama has done, just a little fiercer and faster. But Trump has no ideas at all. He says he will get rid of ISIS “fast.” How? Not a clue. He has also said he would form an anti-ISIS coalition of the region’s nations, a tough task given that they fear and loathe one another more than they fear and loathe ISIS. How would he do this? By holding “meetings,” he told the New York Times, as if diplomats—American, Russian, European, and Arab—haven’t held hundreds of meetings already. Trump doesn’t seem to recognize that some of the world’s problems are simply hard, maybe intractable. He seems to think that the world’s a mess because American leaders are “very, very stupid” and that the globe’s bad guys will snap to order with a tough guy like him in the White House.

Trump may have an idea, after all, of how to crush ISIS “fast,” and if my suspicions are right, it’s his most dangerous idea of all: I suspect he thinks he can make the jihadi commanders cower by threatening to incinerate them with nuclear bombs. Richard Nixon tried this with North Vietnam, telling his aides to put out the word that he was a “madman” who could do anything, even go nuclear, to avoid losing. At least Nixon, it turned out, was bluffing. Would Trump be? Would he feel compelled to follow through on his threat if they scoffed? He has revealed himself, on several occasions, to have a cavalier, even clueless attitude toward the bomb.

And it’s worth noting (as the New York Times reminded its readers, who probably haven’t had cause to ponder these matters for a quarter-century or so, on Wednesday) that, when it comes to using nuclear weapons, the president decides and acts alone; the system is set up that way because, in the event of a surprise attack, there would be no time to consult with the National Security Council, much less with Congress. Electing a president bestows upon a single man or woman the power to blow up the world.

Former diplomat Richard Burt told an enlightening story to Politico about Trump’s notion of a tough negotiator. Around 1990, when Burt was U.S. ambassador to the Soviet-American nuclear arms talks, he ran into Trump at a reception in New York:

According to Burt, Trump expressed envy of Burt’s position and proceeded to offer advice on how best to cut a “terrific” deal with the Soviets. Trump told Burt to arrive late to the next negotiating session, walk into the room where his fuming counterpart sits waiting impatiently, remain standing and looking down at him, stick his finger into his chest and say, “Fuck you!”

Needless to say, that is not how Burt maneuvered the talks so that presidents George H.W. Bush and Boris Yeltsin came to sign the START II arms-reduction treaty in 1991. One wonders if Trump thinks it might have been how it happened and if he thinks that’s how to handle adversaries today. Trump has said, “I know more about ISIS than the generals” and, just in August, “I know far more about foreign policy” than Obama.

My guess is he really believes these things.

Most of Trump’s dangerous qualities boil down to these two fundamental dangers. He knows very little but thinks he knows a lot. And most of the things he doesn’t know, he doesn’t know they’re worth knowing.

Correction, Aug. 8, 2016: An earlier version of this article misidentifed Crimea as Ukraine and misstated that the former is an island. Crimea is a peninsula. (Return.)