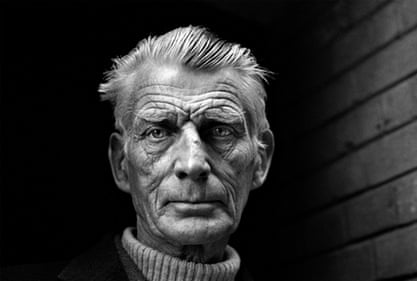

It was 1981 and we all headed down into the dark of the Studio theatre of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. We were going to see a second-year all-female student production of Waiting for Godot. My girlfriend, Anat, was playing Pozzo and Jenny and Amanda and Charlotte were in it. Up till then our offerings had been like exercises but this was different. I became engrossed, then lost and upset, and finally deeply moved. I forgot I was watching fellow students and instead found myself puzzled how a work of such seeming abstraction could shift my emotions so readily. Who was Samuel Beckett and how did he come to write such a play?

Beckett went to school in my hometown of Enniskillen, the county town of Fermanagh. The town is on an island at the confluence of Lower and Upper Lough Erne, a huge body of water connected to the Shannon through a series of locks that makes it the longest waterway on the island of Ireland. Lakes and islands, rushes and reeds, fowl and fish are there and wooden clinker-built boats and shiny copper spoon baits to catch the hungry pike in September. Venture down the lough to the islands and you soon come across signs of the area's pre-Christian past. There are two-faced carved stone Janus figures and Sheela na gigs, female fertility figures holding their vaginas open, and scary open-mouthed deities, receiving or transmitting, the likes of which I've only seen in Mexico.

On top of this stone-deep quiet there is a layer of Celtic Christianity. The monastic island of Devenish is the jewel, in many ways the symbol, of the county, representing self-sufficiency and a commitment to beauty as something vital and sustaining. The lough was a great highway to the interior of Ulster. Enniskillen – from the Irish Inis Ceithleann (Cathleen's Island) – is the seat of the Maguires, a natural island fortress and river toll point from where they controlled the trade between Ulster and Connaught with their friends the O'Neils in Tyrone and the O'Donnells in Donegal. After the defeat of the Irish Bardic order the town became effectively an English garrison town complete with two regiments, the Inniskilling Dragoons and Fusiliers, and Portora Royal School, where the young Samuel Beckett was sent to board.

I have often wondered since that first encounter with Beckett's work what effect his formative years at Portora and his engagement with Enniskillen and Fermanagh had on him. As a child growing up there I was for the most part very happy. I was brought up in what was left of the old streets on the island. In the 1960s, in a gross act of social engineering, some civil servants decided to move the people off the island, destroying Georgian housing, and replace them with roads and car parks. In Beckett's time, however, the town and its people were connected entirely to the lough, their homes and streets ran directly down to the shore.

This inland island and its watery, reflective hinterland must have exerted its moods and atmospheres on the young Beckett and in particular at Portora. Portora in Irish is given to mean "the Place of Tears", for it was from here in the long ago that the dead bodies of Christians would be taken by boat on their final journey down the lough to be buried in the consecrated ground on Devenish.

Portora, where Oscar Wilde had been at school before him. Portora, where Beckett found an outlet for his energy on the rugby and cricket playing fields (Wilde loathed sports). Isolated as Wilde was here, it was at Portora that his fascination with the literature and culture of ancient Greece began. Those primary obsessions surely begin early. We may allow ourselves the excitement of revelations along the way, but all artists return to the comfort or discomfort of those early obsessions.

It's exciting to conjure with the idea that somehow what we feel towards our island town and the lough might be the same source of feeling that fed the imagination of the teenage Beckett. I shall never know. However, when the idea of holding a festival in the town was first put to me by Sean Doran (its director and founder) I was confident it would be a good fit. An international festival here in the quiet heart of Ulster. Now, of course, Samuel Beckett's friends are coming from Dublin and Belfast and London and Paris and New York to connect with his work and honour the man whose writing continues to illuminate and comfort us. We for our part can only do our best to treat our guests with the civility and good humour that was apparent in him.

The saying goes that, "Half the year Lough Erne is in Fermanagh and for the other half Fermanagh is in Lough Erne." Fermanagh people love these words as they explain exactly the relationship we have with water, sweet water, deep water. We are the boys and girls of the lough. The powerful draw of the silver lake, the way the mist hangs a couple of feet above the Lough on a hot summer's morning, and the blue, blue, electric blue of the kingfishers and dragonflies. Marlon Brando once said, "Nostalgia is the most powerful drug of them all."

To take a boat today west from Enniskillen is to travel into our ancient past, but it is the present that takes hold of your senses and pushes you towards calm reflection on the fundamentals.

There were two drama societies in Enniskillen when I was growing up, St Michaels and the Enniskillen Amateur Dramatic Society, and I had the pleasure of working with them both. When I acted with the local companies it was always in church halls and school gyms, but in the 80s the town finally got its own theatre. The Ardhowen theatre has gone on to be a huge success, thanks mostly to Eamon Bradley, its first programmer and manager, and with no little help from my dear, departed cousin Imelda McLernan. For the opening of the theatre in 1986, it was decided I should approach someone who we all felt represented the best of us, as Ulster people, and that was James Ellis. Jimmy Ellis, now sadly recently departed, as well as being an inspiring actor, was a writer, director and humanist. Jimmy immediately agreed to the gig and we flew over together to Belfast, hired a car and headed for Enniskillen. I was nervous about the event and asked Jimmy a few times on the way down what he was going to say but he just kept shaking his head, "Ah, I'll think of something", and so there we all were in our black ties as Jimmy walked on stage. What he said has never left me.

It was 1946 and the Polish government and the city of Warsaw asked Tyrone Guthrie to come and direct a production of Hamlet. Guthrie accepted and a few months later found himself making the arduous journey across a war-ravaged Europe. He was met in Warsaw by a local delegation, which drove him through the devastated city. He saw people living in makeshift buildings and surviving amid the rubble. Then they turned a corner into the main square and stopped outside a large new building. Everyone got out and the leader of the delegation turned to Guthrie and said, "Mr Guthrie, here is your theatre." Taken aback, Guthrie asked how it was possible, with people so desperate for housing, that their first act had been to build a new theatre. "Ah," came the reply, "but the theatre is everybody's home."

Jimmy, as ever, had hit the nail on the head, for the theatre is everybody's home, an abstract unclaimable space, where we are free to ask the hard questions and also to lose ourselves in the absurdity of life.

I am about to direct Beckett's play Catastrophe for this year's festival. It's a political play dedicated to Vaclav Havel, the playwright, poet and former president of the Czech Republic. Beckett was moved to write it not only because of Havel's writings, but because he admired Havel's moral courage in speaking out against the regime. Havel was in prison when the play was first performed in Avignon as part of an evening of drama designed to bring attention to the plight of the imprisoned writer.

The fact that Beckett, who left Dublin for Paris soon after the second world war broke out, remained a political writer is hardly a surprise. He saw first hand the horror of fascism roll across Europe and recognised it, too, in the totalitarian state. Catastrophe explores these themes, in particular that of the individual manipulated by the state once-removed.

Havel later wrote how lifted up he was on hearing of the events in Avignon and the play dedicated to him by Samuel Beckett. He sadly never got to meet Beckett but tells a story of how on the eve of his inauguration as president of Czechoslovakia he couldn't sleep. In frustration, he decided to wrap up and step out into the Prague night where the people had been celebrating their newfound freedom. He walked the empty streets through the cans and bottles of the party and turned a corner to see written with spray paint on a wall, "Godot Has Come". It stopped him in his tracks and he took it as a sign from Beckett that all would be well.

This year's festival has some very beautiful and beautifully curated events. The Yiddish Godot from New York, the powerful and pure musicality of Gavin Bryars, Winterreise, Klaus Maria Brandauer with Krapp's Last Tape… Samuel Beckett has left us with a body of work so full of riches as to make anyone feel humbled on first encounter. But close encounters with his work reveal a man working diligently to provide us with a kind of psychological toolkit. Here we find wrenches and screwdrivers to prize off the lid of the conscious and lamps to light the dark corners of unconscious thought. The explorations we make with him into the seeming dark, very like our own cave-riddled limestone landscape, although timorous at first, become explorations we find ourselves queuing up to make because of the revelations and affirmations of life that appear at journey's end.

I picture Beckett in the windy autumn with the chestnuts falling and his hands thrust deep into his coat pockets. He stops at the lock gates by the castle, watchful and still, less aware of the fact that it was the site of a ford between Ulster and Connaught and more interested in that part of the castle that some old Portorans managed to blow up in an experiment of some sort. Suddenly, the kingfisher catches his eye and he finds himself looking at the lough, Lough Erne, and him with no idea that the thoughts he is having are being carried by its deep waters to the broad Atlantic and may one day change how we feel towards one another.

On the other hand, he may just have heard the story that WG Grace once hit a six straight out over the Trinity College Dublin railings and through a shop window in Dawson Street.

Q&A: Adrian Dunbar

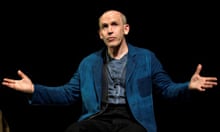

Most people will know you for your film and television work, including critical hits such as Hear My Song, My Left Foot, Ashes to Ashes and the police drama Line of Duty. So how did you come to be directing a little-known Beckett play at a small festival in Enniskillen?

The actor Jim Norton, says, very wisely, that every actor has to give himself a scare once a year, and for me, that means going back to the theatre. I trained to be a theatre actor, I love the live gig, the transference between an audience and a performer. And to be involved with a festival that happens to be in my home town is a huge bonus.

You've been involved with the festival since its inception three years ago – how do you see it evolving?

There's a real question mark over whether it will continue to exist and that's largely due to the bureaucracy of the organisations that fund the festival. The fact is that festivals are mostly run by one or two dedicated individuals, who get very little money and they're doing it as a labour of love. Unfortunately, the funders treat them as if they're big organisations with lots of staff and overload them with paperwork.

You'll be directing Catastrophe, your first experience of directing a Beckett piece. Is it a daunting prospect?

No, I'm looking forward to it. Beckett was the most thorough of playwrights. He tells you what to do and if you've any humility at all, you'll take his advice.

Is that restrictive or liberating?

For directors, it's a huge challenge because they have to take their egos out of the process. It takes a huge amount of discipline and hard work, especially from the performers. You need really brilliant actors to do it because they have to strip away so much, so that the meaning becomes very apparent and clear.

You'll be taking the audience to a "mystery location" for the performance. The use of unconventional venues seems to be a feature of the festival.

One of the things that's wonderful about having a festival in a small town like Enniskillen is that we don't have lots of purpose-built venues so we have to be creative about where we place events. Fermanagh is a very spiritual place, and once you use the natural settings as a context for Beckett's work something amazing happens.

[In the first year of the festival] a group of about 80 of us met at dawn and took a boat down the lough to White Island, where we had some readings from Stirrings Still. Setting off in the half-light, back into a very untouched ancient landscape, everyone hushed and quiet, was very powerful. Then coming back on the boat with the light up, drinking tea and eating toast, everyone feeling energised… it's a really unique and intimate experience.

You seem to be able to switch between acting and directing with ease. Is that part of a deliberate plan?

All actors have dry spells, and when I couldn't get any work, instead of sitting around, I got into directing and writing screenplays [he co-wrote the Bafta-nominated Hear My Song about Irish tenor Josef Locke with Peter Chelsom]. I love the variety that I have in my career at the moment. It's something I've created and I don't want to step away from it now.

Your most recent TV role was as Superintendent Ted Hastings in Line of Duty. Were you surprised by the success of the second series?

It was a nice surprise, of course, but we always knew we had something really good. I think we kind of lost our way in television for a while, but then we were reminded, from northern Europe in particular, that it's difficult to beat a good story and a central character we can really engage with. I think part of the show's success is that it follows police procedure. It doesn't have silly plot twists like journalists turning up a really important piece of information – that doesn't happen at all.

So will you be appearing in the next series?

I hope so, unless the writer [Jed Mercurio] decides to kill me off! I'm keeping my fingers crossed that I'm going to be all right.

Interview by Joanne O'Connor

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion