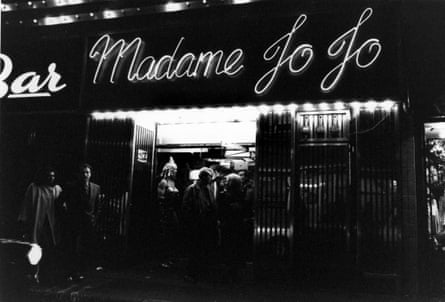

The news that Madame Jojo’s has had its licence revoked and the doors locked will have stirred a familiar sense of doom – not only in those who patronised that quirky club, but also in the wider fraternity of Soho lovers who feel that the place is rapidly losing its salty charm and succumbing to a wave of upward mobility. The longest queues in this part of London now tend to be outside the latest “no bookings” tapas bar, rather than for some form of entertainment that promises to flout the rules of conventional society.

My first memory of Soho was of a place called the Doll’s House in the 1960s. Every year, the grammar school I went to in Vauxhall, just south of the river, held a founder’s day service in St Martin-in-the-Fields. There was a thrill in going up to Trafalgar Square that was unconnected with that grand old church. Just round the corner was Soho, a place where, so legend had it, schoolboy dreams could come true. Soho was the place I had been specifically warned about, both by headmaster and parents: as it might have been on the old maps, “here lurk wicked things”. Accordingly, when this worthy occasion finally ground to a halt around lunchtime, the more adventurous of us schoolboys would nip down the nearest alleyway to turn our blazers inside out, thus disguising our age and employment status. Then it was straight to the Doll’s House, a strip club that allowed us in, and frequently offered a group discount.

Later in the decade, our focus shifted to music, and the Doll’s House made way for the Marquee Club in Wardour Street, where the likes of Jimi Hendrix would be hopelessly sold out, but where Procol Harum could be relied upon to offer a not-entirely-unsatisfactory alternative. A beer was usually available, but failing that, it was enough to sniff the heady atmosphere, as the walls, floor and ceiling were always awash with alcohol.

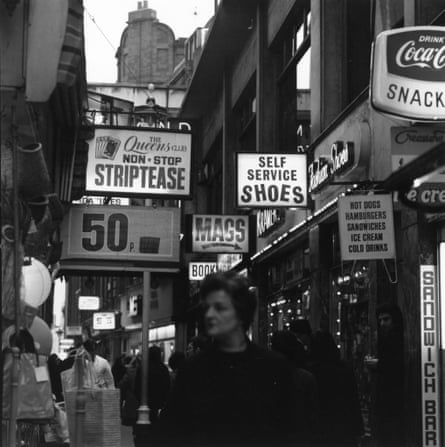

Thus, memories of Soho from the most impressionable age were of wine, women and song, although not necessarily in that order. Carnaby Street was never a particular attraction. This overpriced flea market seemed to have peaked before it really got going, with Ben Sherman shirts, Levi’s Sta-Prests and monkey boots all available much nearer to home at a fraction of the price. The larger sense of Soho was different; always commercial, but somehow never commercialised, it had an intoxicating whiff of the attainably forbidden. This was a naughty place where all sorts of fun could be had for a few bob and a smidgeon of chutzpah.

The 70s are widely regarded as representing a modern-day nadir. The old strip clubs were already in retreat, hounded out by dirty bookshops and video outlets that invariably promised more than they delivered, not to mention the clip joints where lovely ladies would entice you to buy questionable alcohol at exorbitant prices and then disappear, leaving empty promises floating in the air. This flaky edifice was widely regarded as being propped up by bent coppers.

The Marquee Club was still there, though, now joined by punk venues such as the Vortex, where an appearance by Ed Banger and the Nosebleeds was only ever an amphetamine heartbeat away. The Soho mackintosh was seedy on the outside, but inside out it could still reveal itself as a coat of many colours. Once, sauntering along Wardour Street, I took a detour into Meard Street. In this tiny thoroughfare was an establishment called the Golden Girls Club. I never found out what went on inside, but I had, and retain, my suspicions. Now Meard Street is home to a very good tailor and a most toothsome hamburger joint. Then, it was a place of secrets.

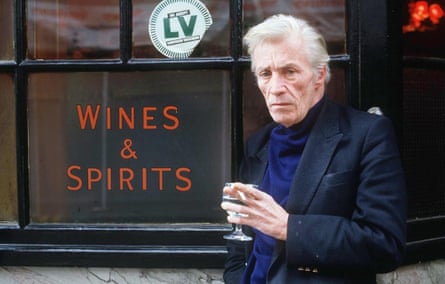

Underpinning the shifting sands of fashion, Soho’s drinking dens proved to be a solid rock. The French House, with its Gallic hauteur, continued to insist that beer should only be consumed in half-pint glasses and that sitting down was not really an option. The Coach & Horses, run by rude Norman Balon, was a magnet for those desperate to catch a glimpse of Jeffrey Bernard and his drinking buddies.

Real rudeness, delivered with breathtaking verve by Muriel Belcher and her descendants, was always on tap at the Colony Room, an upstairs bar decorated in a noisome shade of green, which was periodically enlivened by the antics of Francis Bacon and his crowd of in vino veritas cronies. The Colony’s real claim to fame, in the good old days of strict licensing hours, was that it would sell you drinks when other places couldn’t – a haven for those in search of the lost afternoon. Now that any old boozer can stay open all day, that cachet has been sorely diminished. So, too, has the expectation of bumping into a famous artist, or, more likely, of having him or her trip over you. The Soho of recent yesteryear was an egalitarian place, where the famous, notorious and mundane could freely mingle. The pursuit of pleasure, however dubious its form, was the uniting factor.

Soho continued to flourish in the 1980s as the New Romantics sashayed into town in a colourful blizzard of cross-dressing and tons of make-up. The headquarters were Steve Strange’s Blitz nights. Boy George was a notable figure, often engaged in some form of domestic row with his great friend Marilyn, of cheekbone fame.

Those with an earthier taste in music and company would always head for Gaz’s Rockin’ Blues, a non-stop and rather frantic disco purveying ska, reggae, soul and classic rhythm and blues. From the 80s also emerged the Groucho Club, a members-only establishment where media folk gathered to share gossip, snort cocaine and occasionally partake of a hamburger when energy was low.

Throughout all these years, the name of Paul Raymond was prominent. He was a substantial property owner in Soho and, like Peter Stringfellow, his main interest was in displaying female flesh to an avid audience. Raymond’s Revuebar was the most famous strip club in Soho, a place touched with just enough respectability to keep it heaving with businessmen. For a time in the 60s, Raymond also owned Madame Jojo’s, where that more considered form of striptease – burlesque – was a staple. Raymond was also alive to the benefits of diversification. Alternative comedy found a home in the Revuebar, giving a chance for lucky punters to be shouted at by Alexei Sayle, or enigmatically entertained by Rik Mayall and Ade Edmondson in their early incarnation of 20th Century Coyote. Laughter (and heckling) were always part of the appeal.

Since these golden years – admittedly, tarnished ones – Soho has been in decline. Among the much-trumpeted fleshpots and drinking dens sparkled a vast array of independent businesses, including coffee shops that sold the real thing, delicatessens and proper food shops. These have gradually disappeared, mostly because of rent hikes. Similarly, the Marquee Club has gone, and that great outpost of jazz, Ronnie Scott’s, which was never cheap in the first place, has been redesigned as a venue for very expensive food with the odd saxophone solo thrown in. The Groucho Club has been joined by Soho House, which makes the world a very cold place for those who have no time for braying monsters of self-importance.

The general consensus is that what is left of the spirit of old Soho has moved to the east and south of London, where rents are affordable and local public opinion has not yet identified the various locales as depraved hotspots of vice. Their time will doubtless come. The sadness of Soho’s twilight years is that the area has been caught between two irresistibly destructive and interlinked forces: the relentless pursuit of profit among landlords, and the widespread and appalling imperative to gentrify. Soho’s history tells us that it has always been a safe refuge for outsiders, both in terms of nationality and, increasingly, of the artistic persuasion. It was a place where people dared to be different. Indeed, were encouraged to be so.

The current mania is for homogeneity: everywhere should be the same and, because this is the West End of London, the same means upmarket. In order to satisfy the increasingly rapacious demands of landlords, the entertainment to be obtained in Soho will come at an increasingly high price and will be of an increasingly predictable nature.

An evening at Madame Jojo’s was never a guaranteed success, even with all the swanky velvet and glittering mirrors. What was often guaranteed, though, was a lifting of the eyebrows and the spirits. Barring some miraculous reprieve, that experience is no more. Soho is now fast becoming yet another centre of excellence in the emptying of wallets.

Paul Raymond is dead, his empire is dispersed and his reputation is not unblemished. Yet the old rogue would have been horrified by what is happening to his old manor, where joy is being increasingly confined.

Madame Jojo’s has been around for about 50 years, which makes it something of a grande dame. As has been pointed out, it was a rarity – even in Soho – in having a seven-nights-a-week 3am licence. Violence has not been a feature on these premises before and Westminster council’s response to one isolated incident has been draconian. Bouncers were apparently involved, as was a disgruntled patron. This should come as no surprise. Bouncers and disgruntled patrons have been at it since the dawn of nightclub time.

The comment by Marcus Harris, a promoter at Madame Jojo’s, cannot be improved on: “In my opinion, it seems that the council just used the incident as a good excuse to take away the licence. If you look at the way the area is changing, they clearly don’t want a late-night drinking presence anywhere in Soho any more. They want to make Soho about families – shopping, going out to eat, going to the theatre. The bars shut at 11 and you’re home by midnight.” Soho, for better or worse, has never been about getting home before midnight.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion