How much should one subway station cost? The city of Toronto has an answer. The plan to extend transit in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough winds back at least a decade: at one time the plan was a seven-stop light-rail line; later a three-stop subway. Today, Scarborough is preparing to replace its six-stop automated train with just one single, solitary subway station, for a mere C$3.35bn (£2bn).

Is that a wise investment? Time will tell, but in a recently unearthed 2013 assessment the transport agency Metrolinx calls it “not a worthwhile use of money”. Many voters in Scarborough feel differently, and Toronto’s mayor, John Tory, has no plans to change course.

But if Toronto may be about to purchase the most expensive single subway stop in history, it wouldn’t be alone in sinking good money into bad projects. White elephants are everywhere.

America’s ‘bridge to nowhere’

Back in 2005, Alaska scored a spending coup in Washington, DC. In that year’s mammoth infrastructure bill, the state managed to peel off $223m for a bridge to connect a town of 80,000 people on the mainland to just 50 on Gravina Island. It would have been longer than the Golden Gate bridge, and higher than the Brooklyn bridge.

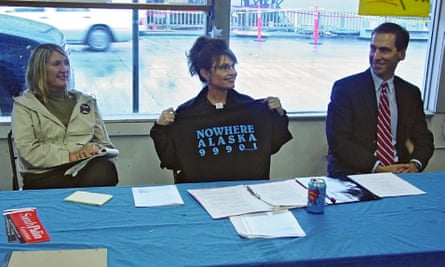

Due to how few people it would reach, it was quickly dubbed “the bridge to nowhere”. The moniker became a curse following Hurricane Katrina: senator Tom Coburn tried to reallocate some of the money for the Gravina Island bridge to help rebuild New Orleans. When his attempt failed, senator John McCain vocally assailed it as a classic pork-barrel project. Gubernatorial candidate Sarah Palin, meanwhile – one day to be McCain’s choice for vice president – supported the bridge, once proudly displaying a T-shirt reading “Nowhere, Alaska”.

In the end, even Palin decided it was a bad idea. In 2007, as governor, she put the brakes on the project (though, despite what a McCain-Palin 2008 campaign ad claimed, she did not stop it entirely). It was finally scrapped in 2015.

South Korea’s Four Major Rivers project

In 2009, South Korea launched the Four Major Rivers Restoration project. Its goal was to improve water quality in the Han, Nakdong, Geum, and Yeongsan rivers, and to make parts of South Korea more resistant to floods and drought. The latter part of that plan involved building 16 dams. Cost? 22 trillion won, or about £15bn.

For their money, South Koreans do not appear to have received all they were promised by the former government of Lee Myung-bak. Since the project was declared complete in 2011, it has been slammed by the country’s Board of Audit and Inspection: in 2013 it found that “due to faulty designs, 11 out of 16 dams lack sturdiness, water quality is feared to deteriorate … and excessive maintenance costs will be required”.

Earlier this year, South Korean president Moon Jae-in stepped in – and ordered yet another audit.

Berlin’s airport: coming soon (forever)

In 2006, Berlin’s new airport was projected to cost about €2bn and open in 2012. Five years later, not only has its opening been pushed back to 2019 and its budget ballooned to more than €5bn (£4.6bn), but so has the number of passengers expected to pass through it.

Initially, it was thought that by closing Berlin’s two operating airports, Tegel and Schönefeld, the new Berlin Brandenburg airport (BER for short) would have to handle around 27 million passengers per year. But in 2016 Tegel and Schönefeld saw 33 million passengers combined. The crown on this classic white elephant: Germany’s government currently spends €16m a month just to maintain the unfinished airport as it is.

What happened? A litany of design and construction issues, as well as accusations of corruption. Tests of the fire alarm system revealed so many problems that the corporation in charge of the airport suggested hiring 800 low-paid workers to stand around the airport and send notifications via mobile phone if they smelled smoke or saw a fire.

By 2015, when the airport was supposedly two years from opening, 150,000 defects had been found in the airport – 85,000 of them “serious”, according to one official. So much, it has been said, for German engineering prowess.

The $51bn town

Prior to 2014, Sochi was a sleepy, sub-tropical resort town for well-heeled Russians on the Black Sea. Once it was designated host city for the 2014 Winter Olympics, however, an army of contractors and construction workers descended on the city to build 49 new hotels, 13 new and renovated train stations, five new schools, six medical centres, and 200 miles of road (including 22 new tunnels and 55 new bridges), according to a New York Times report.

The cost: an estimated $51bn. By comparison, the 2016 ummer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro – a much larger event – are estimated to have cost around $13bn.

In 2016, the Olympics site boasted that Sochi was “still basking in Olympic afterglow”, but other accounts suggest that might only be partly true. Photos published in 2015 showed the Sochi Olympic site abandoned, and the roads and hotels surrounding it empty. However, the private investment that flowed to the city in the run-up to the games – particularly for new real estate – has meant that for some, Sochi is now reportedly a retirement mecca.

Spain’s crumbling masterpiece

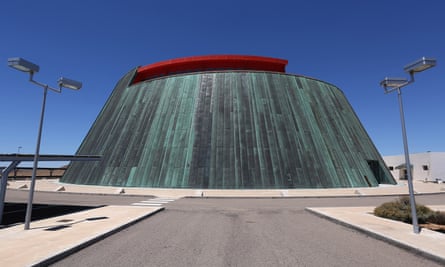

Recently, architect Santiago Calatrava’s name has become synonymous with the massive Oculus exoskeleton jutting up in lower Manhattan, adjacent to Ground Zero. But in the late 1990s, Calatrava’s name was linked to an even grander project: Valencia’s City of Arts and Sciences. The anticipated build cost for the original design of the massive complex, which now includes a performance hall, two bridges, a planetarium, an opera house and a science museum, was predicted to be €300m. But further modifications by the region’s government saw the price more than treble, eventually surpassing €1bn.

The complex has been plagued with problems, most notably involving the roof of the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia opera house: the tiles covering it came off, which Calatrava’s team blames on incorrect application, rather than design. In 2014, Valencia’s government decided to replace the roof entirely, for a further €3m. That same year, Valencia announced it was suing Calatrava – who was paid nearly €100m for his work – and his architectural firm for the cost of repairs. But legal issues weren’t new to Calatrava. Two years earlier, he had sued a regional leftwing political party that started a website enumerating all the problems with the buildings (he won).

Despite the expensive mess in Valencia, Calatrava has also continued to win contracts: London’s next major development, Peninsula Place in Greenwich, is a Calatrava design. The Oculus, for the record, has its own roof problems.

The Pearl river bridge

The idea for a bridge to span the Pearl river delta, linking Hong Kong to Macau and Zhuhai and thereby joining together the world’s largest urban conurbation, has been around since the 1980s, but took on new life after Hong Kong was handed back to China in 1997. Construction finally got underway in 2009, with the expectation that the bridge would open in 2016.

That date has come and gone, and the $2.3bn bridge may only now receive car traffic starting in 2018. In the meantime, the project has been plagued by engineering problems, construction worker deaths, soaring costs and allegations of corruption. The last of those problems has the potential to push the bridge’s opening date even further into the future, and costs higher.

Earlier this year, 21 people were arrested over one company’s role in the construction. Two senior executives and 19 lab technicians are alleged to have falsified test results for the concrete, according to a report in the South China Morning Post. At best, that means there are safety concerns; at worst, two-thirds of the supporting pillars and columns might need replacing. China may soon get its very own bridge to nowhere.

The Don Quixote airport

Ciudad Real Central airport wasn’t always destined to be a complete flop. It was conceived in the 1990s, when nobody could have known that the global financial crash would cause the Spanish economy to grind to a halt in the same year (2008) that the airport would eventually open. But how, and why, did a small city of 75,000 people in Castile-La Mancha (home of the famous literary fantasist Don Quixote, which has resulted in the nickname the “Don Quixote airport”) become the proposed site for a major international transit point at all?

As the BBC explained, it “was to be a private project, for private profit”, and prior to the economic collapse, money for projects like it was not difficult to come by via local savings banks, which had local politicians – with eyes trained on infrastructure projects to brag about – on their boards.

In its final year of operation, 2012, the €1bn airport didn’t receive a single flight. Three years later it was put up for sale; one Chinese-led bid of €10,000 was rejected for being too low. It was eventually sold to a local group for €56m and has yet to see any new flights.

The bungle of Benidorm

In the heady pre-recession days of 2005, Spanish savings bank Caixa Galicia funded what has become one of Europe’s tallest white elephants: the In Tempo apartment block in Benidorm. The developer, Olga Urbana, borrowed €93m to build a 47-storey M-shaped tower overlooking the Mediterranean; Caixa Galicia itself put up just €3,100 ($3,650) in seed capital.

What followed was a hilarious nightmare. There were immediate construction and design problems. Most notably, the building’s architect didn’t properly design the elevator for 47 stories: instead, it used plans for a 20-storey building and simply extended the lift mechanism another 27 storeys. As Der Spiegel explained, the architect “failed to consider … that more stories would also mean more use, or that the space would not be sufficient for the necessary amount of additional lifting equipment”.

Despite being mostly complete, the building has yet to be occupied, according to El Mundo, which also recently reported that the building’s mortgage had been sold as part of a €60m deal between its current holders, Sareb, and SVP Group as part of a plan to finally start selling the units. As for its value to sightseers? One reviewer on TripAdvisor summed it up: “Not an attraction.”

Pyongyang’s Hotel of Doom

Construction on the Pyongyang Hotel began in 1987, and by most accounts the building is still not quite ready to, you know, host guests. Officially called the Ryugyong, it has been dubbed the “Hotel of Doom” out of fears that it is structurally unsound.

At conception, the planned 105-storey Ryugyong was meant to be the tallest hotel on earth, complete with casinos and nightclubs. But economics – specifically, the downfall of the Soviet Union in 1989 – ruined the party. Construction has limped on ever since; all told, the building is said to have so far cost £470m.

In July, photos showed it mostly empty, with the exterior works unfinished. But in October, on the strength of comments from tourists to North Korea, speculation grew that the hotel could soon open. Watch this space in another 20 years.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion