Coffee is one of the most popular drinks worldwide, with countless cups of the dark, alluring elixir brewed up each day. And, lucky for those coffee-guzzlers out there, mounting data suggest it’s good for you; moderate coffee drinking has been linked to lowered risk of cardiovascular disease, liver diseases, diabetes, and an overall lowered risk of dying too soon.

But, as coffee-lovers happily continue sipping their morning fix with a dash of self-satisfaction, it’s worth noting that not every cup of coffee is equal. Brewed coffee can vary wildly in its flavor and chemical make-up, particularly the chemicals linked to health benefits. Everything that happens before the pour—from the bean selection, roast, grind, water, and brew method—can affect the taste and quality of a cup of joe.

So far, there’s little to no data on the health impact of drinking one type of coffee over another. In studies linking coffee to lowered risks of disease and death, researchers mostly clumped all coffee types together, even decaffeinated coffee, in some cases. But, there is a fair amount of data on individual components of coffee that are flavorful and beneficial—and how to squeeze as much them as possible into your mug. Here’s what the science says:

The Components

There are more than 1,000 chemicals in a typical cup of coffee. While scientists haven’t yet teased out each one individually for closer examination, they have nailed down the big players in terms of taste and potential health benefits. To take a stab at brewing the best cup of coffee, here are some key coffee components to consider:

Caffeine: Thanks to coffee drinking, this stimulant is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive drugs worldwide. Caffeine enhances perception, reduces fatigue, increases abilities to stay awake, and may help improve long-term memory. In addition to the pick-me-up, caffeine is linked to boosting metabolic rate and energy expenditure, and it may reduce the risk of developing metabolic syndromes. Current dietary recommendations suggest that up to 400 milligrams of caffeine a day can be part of a healthy diet—about 3 to 5 cups of coffee a day depending on the brew. More than that can cause anxiety, restlessness, irritability, stomach problems, fast heartbeat, and muscle tremors.

Chlorogenic acids: Around 45 of these phenolic compounds have been found in coffee. Along with their breakdown product caffeic acid, the compounds have been linked to lower risks of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. They have also been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties.

Trigonelline: This bitter alkaloid has been linked to protecting the brain from damage, blocking cancer cells from moving around, combating bacteria, and lowering blood sugar and total cholesterol.

Kahweol and cafestol: These diterpenes, which contribute to the bitter taste of coffee, have been linked to preventing and battling cancer cells. But, they’ve also been linked to raising cholesterol.

The Bean

Though there are around 70 types of Coffea—the flowering plants that produce coffee beans—two have the lion’s share of the coffee market: Coffea Arabica (Arabica beans) and Coffea canephora var. Robusta (Robusta beans).

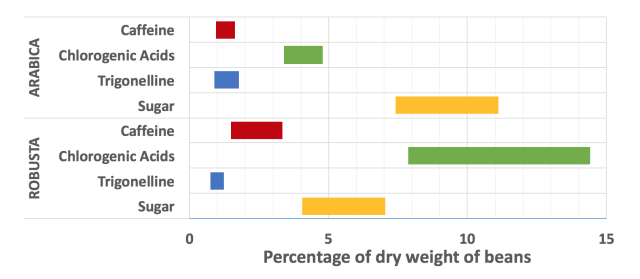

Arabica is the most common bean, noted for its aroma and balanced flavors. Arabica tends to have more trigonelline and diterpenes (kahweol and cafestol). Robusta beans, on the other hand, tend to have more caffeine and chlorogenic acids.

In a 2001 study, researchers looked at the content and laid out the portions according to dry weight. For the study, they pooled 38 varieties of each type of bean (Arabica vs Robusta) and compared the levels of key compounds (They didn’t look at the diterpenes.) The takeaways are below:

The Roast

There’s no standard method for firing up beans or determining roast strengths (light to dark). But, generally, beans are baked somewhere between 180 and 250 degrees Celsius for somewhere between 2 and 25 minutes. The process takes green beans, which have a mild, bean-like smell and makes them into delicious, toasty brown beans. During the scorch, sugars and fats degrade, amino acids and sugars react with each other, and degradation products spark chain reactions. This all culminates in the formation of dozens of aromatic compounds that make up that enticing coffee bouquet. Those compounds include aldehydes, ketones, furans, pyrazines, pyridines, phenolic compounds, indoles, lactones, esters and benzothiazines.

Contrary to some common beliefs, the amount of caffeine in the beans doesn’t change that much with roasting. Some studies have reported slight decreases in caffeine in darker roasts, but some have found no differences.

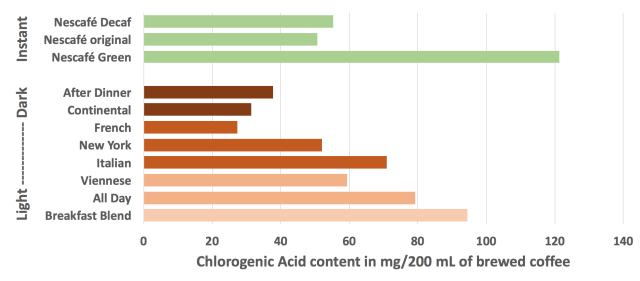

But for chlorogenic acids, more roasting leads to less of these beneficial phenols, according to a 2013 study that compared coffee blends of various roasting levels. So, for a bigger helping of the acids stick with a light roast. But, if you're a fan of instant coffee, no need to worry as the freeze or spray drying process to make the instant stuff doesn’t destroy the useful acids. For instance, in the study, the instant Nescafé Green had some of the highest levels of chlorogenic acids as it contained green, un-roasted coffee beans.

The Water

Purists might assume that clean, distilled water with no contaminating chemicals would brew the best cup. But, according to a recent study, added positive ions, often found in “hard” water, are good at grabbing the flavorful compounds in coffee. In particular, calcium and magnesium ions were best at snatching flavor compounds without otherwise altering the coffee taste.

The Grinding and Brewing

For the grind, basically the more pulverized the beans the more you’ll get out of them. In one study, researchers found that using a standard home grinder for 42 seconds compared with 5 seconds doubled the amount of caffeine squeezed out of a 37 gram portion that was then brewed with a standard drip coffee maker. Another study found that having more particulates—the fine powder that turns into coffee sludge—also increased caffeine content.

Brewing methods are also critical for squeezing out the goodness of the beans. There’s a variety of methods to choose from: Brief boiling (Turkish), steeping (French press), Filtering (drip coffee), and pressurized (espresso).

Basically, there are three factors that determine how much you’ll get out of your beans: pressure, time, and turbulence during the extraction.

Espresso machines, which force hot (91-96 degrees Celsius) pressurized (~9 bar) water evenly over fine, well-packed coffee grinds, produces the brews with the most concentrated doses of caffeine. In a 2012 study, Arabica and Robusta espressos measured in at 141-253 mg of caffeine per 100 mL. But, most espresso servings are small, sometimes around 30 to 40 mL.

For more caffeine for your buck, you might want to go with quantity over espresso-quality. In the same study, the same beans packed into a standard drip coffee machine produced java with 57-115 mg of caffeine per 100 mL. For a standard 8-ounce coffee serving, that would be around 135-271 mg of caffeine.

The same was true for chlorogenic acids—they’re more concentrated in a tiny espresso serving, but an 8-ounce serving of drip coffee will deliver more of the beneficial compounds. Sadly, the study didn’t look at the other coffee components or brewing methods (boiled or steeped).

But, the researchers did note that in the drip coffee method, the last drops out of the coffee maker were most packed with caffeine and chlorogenic acids. This suggests that longer steeping times (5 to 6 minutes in the study) would get the most out of the beans.

As for taste, researchers have noted that espresso has some of the richest flavor and creamy texture, owing to a layer of emulsified oils that create a homogenized foam over the liquid. Those oils are likely cut down in drip coffee—thanks to paper filters—but may remain (although not in homogenized foam form) in boiled or steeped coffees.

Additives

Last, after you make your perfect, healthy cup of coffee, don’t go mucking it up with flavor additives. If taste doesn’t compel you, perhaps health reasons will. The latest federal dietary guidelines weighed in on the subject, saying: “although coffee itself has minimal calories, coffee beverages often contain added calories from cream, whole or 2% milk, creamer, and added sugars, which should be limited.”

reader comments

254