Guest post by Sarah Burstein, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law.

Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., Inc. (Fed. Cir. April 19, 2016) Download Opinion

Panel: Moore, Hughes, Stoll (author)

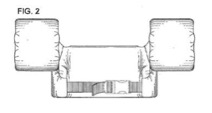

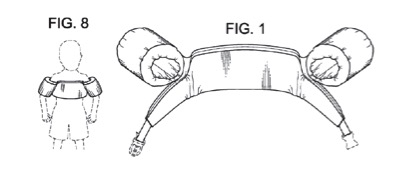

Coleman accused Sport Dimension of infringing U.S. Patent No. D623,714 (the “D’714 patent”), which claims the following design for a “Personal Flotation Device”:

The district court construed the claim as: “The ornamental design for a personal flotation device, as shown and described in Figures 1–8, except the left and right armband, and the side torso tapering, which are functional and not ornamental.” The court, like many other courts and a number of commentators, interpreted the Federal Circuit’s 2010 decision in Richardson v. Stanley Works as requiring courts to “factor out” functional parts of claimed designs. Coleman moved for entry of judgment of noninfringement and appealed the claim construction (along with another issue not relevant to this discussion).

After Coleman’s appeal was docketed, the Federal Circuit disavowed the “factoring out” rule that many had read in Richardson. As discussed previously on this blog, in Apple v. Samsung and again in Ethicon v. Covidien, the court insisted that Richardson did not, in fact, require the elimination of functional elements from design patent claims.

Following this new interpretation of Richardson, the Federal Circuit reversed the district court’s construction of Coleman’s claim. The court stated, for the third time in a year, that district courts should not eliminate portions of claimed designs during claim construction. So it seems that the Federal Circuit’s retreat from Richardson is complete—if that weren’t clear already.

And, for the first time I’m aware of, the court actually explained how it determined whether something is “functional” for the purposes of claim construction. It’s been clear for a while that the court was using a more expansive concept of “functionality” in the context of claim construction than it was using for validity. (For more on this issue, see this recent LANDSLIDE article by Chris Carani.) However, the court hasn’t seemed to acknowledge that disconnect or explain how courts should analyze functionality in the claim construction context. In this case, the court did both. The Federal Circuit stated that the Berry Sterling factors, although “introduced…to assist courts in determining whether a claimed design was dictated by function and thus invalid, may serve as a useful guide for claim construction functionality as well.” (Those factors, discussed here, are very similar to the factors used by courts to determine whether a design is invalid as functional in the trademark context. For more on the trademark test and how it differs from the current design patent test for validity, see here.) Applying the Berry Sterling factors to the facts of this case, the court affirmed the district court’s conclusion that the armbands and tapering were functional.

So in Sport Dimension, it is clear that the Federal Circuit thinks it is important to determine whether an “element” or “aspect” (the court uses those words as synonyms) of a design is functional. And it is very clear that courts are not supposed to completely remove functional “elements” or “aspects” from design patent claims as a part of claim construction. But what are courts supposed to do? Here is what the court said:

We thus look to the overall design of Coleman’s personal flotation device disclosed in the D’714 patent to determine the proper claim construction. The design includes the appearance of three interconnected rectangles, as seen in Figure 2. It is minimalist, with little ornamentation. And the design includes the shape of the armbands and side torso tapering, to the extent that they contribute to the overall ornamentation of the design. As we discussed above, however, the armbands and side torso tapering serve a functional purpose, so the fact finder should not focus on the particular designs of these elements when determining infringement, but rather focus on what these elements contribute to the design’s overall ornamentation.

It’s not at all clear what the court is trying to say here, especially in the highlighted portion (emphasis mine). It seems that perhaps the court is trying to say that, in analyzing infringement, the factfinder should focus on the overall appearance of the claimed design. But if that is what the court meant, then this “claim construction” frolic adds nothing—the infringement test already requires the factfinder to look at the actual claimed design, as opposed to the general design concept.

This portion of the decision also seems to be in some conflict with the court’s decision in Ethicon. In Ethicon, as here, the district court eliminated all the functional portions of the claimed design. Unlike this case, the district court in Ethicon said that all the elements were functional and, thus, the claim had no scope. The Federal Circuit reversed, stating:

[A]lthough the Design Patents do not protect the general design concept of an open trigger, torque knob, and activation button in a particular configuration, they nevertheless have some scope—the particular ornamental designs of those underlying elements.

So Ethicon says that factfinders must look at the “particular ornamental designs” of functional elements. Sport Dimension says they “should not focus on the particular designs of [functional] elements.” These statements could potentially be reconciled by drawing a distinction between the “particular design” of an element/feature and the “particular ornamental design.” But it’s not at all clear what that distinction might be—or whether it makes sense to draw such a distinction at all.

More importantly, it’s not clear what, exactly, the Federal Circuit hopes to gain by making district courts go through this rigmarole. In this case, the accused product looks nothing like the claimed design, as can be seen from these representative images:

Claimed Design

Accused Product

Yes, they both have armbands with somewhat similar shapes and some tapering at the torso. But the overall composition of design elements is strikingly different. You don’t need to “factor out” anything or “narrow” the claim to reach the conclusion that these designs are plainly dissimilar. (The same was true, by the way, of the facts in Richardson.) Even for designs that are not plainly dissimilar, the Egyptian Goddess test for infringement should serve to narrow claims appropriately where elements are truly functional because one would expect those elements to appear in the prior art. So once again, one is forced to ask what the Federal Circuit is trying to accomplish with these “claim construction functionality” rules—and whether the game is worth the candle.

How about it, Prof Crouch?

4.4.1: move all of the hi jack thread comments to another page, catalogued by topic.

…or would the preponderance of the same things repeated ad nauseum in a single place overwhelm the servers (or is there some other “arrangement” that precludes actually making the “ecosystem” into less of a drive-by monologuing internet style “shout-down”…?)

Justice Breyer may even spring for pizzas over the weekend to get it done.

This design patent decision raises another general legal consistency issue of the type noted by the author.

It is axiomatic “black letter law” that a patent claim must be interpreted with the same claim scope for both validity and infringement. [E.g., Kimberly-Clark Corp. v Johnson & Johnson, 745 F.2d at 1449 (Fed. Cir. 1984).] Also, the statutory tests for 103, 112, and most other patent law sections are not different for design patents. Yet the Fed. Cir. case law for design patents has not been that clear. PTO design application examiners and some Fed. Cir. decisions take a narrow view of design patent claim scope as being limited by all the solid lines and their shapes for 103 examination, since in design patents the solid lines of the drawings largely or entirely define the claim. A prior study by Dennis on this blog determined that only about 1.5% of design applications ever get a 103 rejection. In juxtaposition, their is a broad “ordinary observer” comparison test for design patent infringement. Confirmed in Egyptian Goddess Inc. v. Swisa Inc., 543 F.3d 665, 671 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc). Is that consistent with the requirement that a patent claim must be interpreted with the same claim scope for both validity and infringement?

Why do you think that it might be different?

(I do understand that design patent law is horribly crafted and the so-called “no difference” aspect is problematic at best – I am just hoping to understand what you view as the problem here)

I think the problem is that the Fed. Cir. has not considered the need to reconcile its respective decisions on design patent validity and infringement for requisite consistency in claim interpretation between the two. That seems likely to lead to more difficulties with S.J.s as well. This is above and beyond confusion in claim interpretation re functionality, as here.

Thanks – all in all, the entire area of design patents needs a drastic overhaul. I am not sure that taking one bite at a time for any small piece can resolve the overall incongruities that attempting to say “all the normal utility patent law concepts” apply.

“anon” all in all, the entire area of design patents needs a drastic overhaul.

Maybe we should start one of those think tanks.

We can call it the “The Institute for Reform of Design and Logic Patents.” Or somethign like that.

Once again, Malcolm, software is not logic.

Make an attempt to obtain a copyright on logic and let me know how that aspect of software works out for you.

In the meantime, please stop your drive-by nonsense of repeating something to which you have refused to answer the counterpoint to.

That type of internet “shoutdown” helps no one, and only shows your inability or unwillingness (or both) to engage in an inte11ectually honest conversation.

Berry Sterling is dicta, unfortunately elevated into the case law (without much critical thought) by the clerk who drafted PHG. I think the Court in Sport Dimension talked about Berry Sterling because the lower court talked about it. But even after saying the lower court did ok with Berry Sterling, the Court put it in its proper place (i.e., a distracting sideshow) by saying “functional” really means performing a function. When Berry Sterling is looked at in that light, it makes no sense; someday the Court will relegate it to the dustbin where it belongs. As pointed out by Prof. Burstein, the so-called “factors” in Berry Sterling are really trade dress factors that were sloppily put into a design patent opinion by some careless clerk.

And, there is no inconsistency anymore between determining design patent claim scope during infringement (i.e., claim construction analysis of “functionality”) and validity (i.e., design patent is invalid if “functional”). The Court via Sport Dimension and Ethicon straightened out the former, while High Point I straightened out the latter: (“[T]he fact that the article of manufacture serves a function is a prerequisite of design patentability, not a defeat thereof. The function of the article itself must not be confused with ‘functionality’ of the design of the article.”); L.A. Gear, 988 F.2d at 1123 (“[T]he utility of each of the various elements that comprise the design is not the relevant inquiry with respect to a design patent.”).

Thanks Perry

In another piece of news, apparently the USPTO has argued against inventor J Carl Cooper and eCharge Licensing LLC that patents are “quintessential public rights” that can be cancelled/invalidated by the PTAB (rather than a court). An interesting development to be sure as patents are necessarily private rights in my view (and in mine and Ned’s discussions on this same topic near a year ago). This may impact Ned’s appeal.

I think the USPTO should have gone with the line of argument that they are private rights but that they are governed entirely and created entirely as a creature of statute and thus are available to be cancelled by the congress however they see fit. And I wouldn’t be surprised to have the courts so rule exactly that.

This guy apparently argued that: “He said that patents for inventions and patents for land are treated the same way under the law, and argued that the Supreme Court reaffirmed that patents are constitutional private property in a 2015 decision involving government taking of raisin crops.” which is interesting though I don’t think that raisin case really has much bearing.

The raisin case included a block quotation of James v Campbell.

6, the argument is virtually the same argument made to the Federal Circuit in MCM, and which the government apparently made to the Federal Circuit in Patlex: because they are created by statute, they are public rights.

That is your argument as well.

He does not want to “call” them that – just to treat them like that.

Interesting that we are talking about private rights in this context. The law puts the burden on the patent applicant to disclose facts like prior art that may warrant denying his application, because “patents are affected with the public interest” according to case law going back to Scotus in the 1930’s.

Also, don’t forget that Congress was given the power to grant patents by the Constitution “To promote the progress of science and the useful arts…,” which sure sounds like a public purpose.

So which is it? Public or private?

Betty,

The required disclosure is notably apart from the patent application itself which does NOT require incorporation into the patent itself.

Thus it is done in a different context of the Quid Pro Quo exchange.

Also, do not confuse “affected with” and the express nature of the patent itself.

Lastly, your notion of “public purpose” thought is incomplete and does not reflect an appreciation of the Constitutional phrase as a directive power grant (which branch of the government has the authority), nor does it recognize the most basic aspect of the deal: Quid Pro Quo – yes, the “public” benefits, but surely the “public” is not – and can not – be the only “player” in a game that recognizes an exchange. There must be a private entity portion of that exchange.

Life, liberty and property – pinnacle underlying concepts that are necessary for the context of the discussion.

Anon, I don’t see how one can draw a distinction between a patent application and a patent.

The public wants patents to because it wants progress; the public is concerned about patents because unwarranted patents interfere with public commerce.

If you want to say it is really all private, then that is fine, let applicants negotiate with the PTO the way used car dealers negotiate with their customers.

Betty – it is not the distinction between the patent application itself and the patent, but the prosecution file wrapper and the patent application.

Processing the patent application is different from the application itself – this is just a fact of reality.

As to “negotiate,” sorry, but I do not understand the point that you are trying to make. Any sense of “negotiation” is merely one side trying to convince the other that the requirements under the law have or have not been met. This is not like “buying a car” whatsoever, where haggling over value and different price points may be involved. I am not sure that you understand enough about the legal item that is a patent to make a sensible question there.

Anon, patent attorneys negotiate with examiners all the time.

Agreed, it is not like buying a car because the patent that may/will result from the negotiation is affected with the public interest, so rules imposed on attorneys and pro se applicants require candor and good faith. Used care sales negotiators are not usually held to those standards because it is a private transaction.

Betty,

The negotiation is different in kind – not just degree.

I think your attempt to use “negotiate” as some type of proxy for public/private just will not work.

You are aware (I hope) that from the very beginning of the patent system that the patent right was desired to be a fully alieanable property. Our system is built on that premise. Over on PatentDocs they featured a story on a couple of award winning historians that detailed this.

Anon, how does alienability help your argument that a patent is simply a private right?

Agreed, that a patent owner negotiating to sell his patent can act like a used car salesman, but not when negotiating with the PTO.

Alienabiltiy is a direct aspect of private property.

Another perfect example of a design patent case discussion being hijacked by an unrelated issue. Sigh.

Perry,

Not by a long shot limited to design patent cases.

Perhaps another “attempt”** at a parallel blog space where ALL such hijack posts could be shunted too…

Make it an “automatic” move, please.

**As I recall the ill-fated (and predicted very short duration) last attempt, perhaps this one could be sorted by “topic,” and all of the ad infinitum (ad nauseum) drive-by’s could be co-located. Such would save Malcolm nearly his entire “four hours” per week of posting here…

😉

In case you guys didn’t hear yet, “the slants” is under appeal to the USSC from the office.

You should check out the latest with the NFL’s Washington team…

Nice article, thank you.

With arms in “water wings” which are attached to the chest, how well can someone swim over to a rescue boat? If not, then is it no longer functional? Just curious.

Funny question, Paul. I believe the intent of these wings/chest designs is to keep the head out of water for very beginning swimmers (some models allow detachment and exclusive use of the wings once the child has learned to keep their head up). So, the toddler wearing the full unit probably isn’t going to get across a wading pool, much less over to a rescue boat. 🙂

one is forced to ask what the Federal Circuit is trying to accomplish with these “claim construction functionality” rules

Kurtz: “Are my methods unsound?”

Willard: “I don’t see any method at all, sir.”

Unfortunately I don’t think the CAFC as a whole ever thinks too deeply about “what it’s trying to accomplish”, especially when it comes to design patent law. Given that the accused product so plainly does not infringe the claimed design, this opinion is ridiculous and pointless. The fact that they marked the opinion as precedential is disturbing.

For the curious:

Richardson: LOURIE and DYK, Circuit Judges, and KENDALL, District Judge.*

Samsung: PROST, Chief Judge, O’MALLEY and CHEN

Ethicon: LOURIE, BRYSON, and CHEN

Sport Dimension: STOLL, MOORE, HUGHES

Not sure exactly what “disturbs” you…

Comments are closed.