- News

- lifestyle

- books

- book-launches

- Book Review: A deeply satisfying, provocative work

Trending

This story is from September 30, 2015

Book Review: A deeply satisfying, provocative work

This is not an easy book to read, especially if you like your myths racily retold.

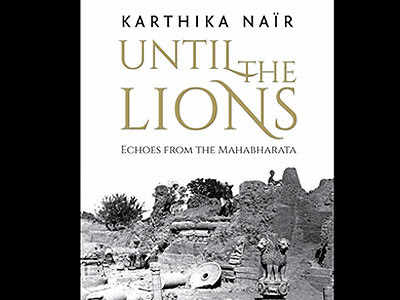

Book : Until The Lions : Echoes from the Mahabharata

Author : Karthika Nair

Publisher : Harper Collins India

Pages: 288

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus famously observed that you never step into the same river twice. It would probably be just as accurate to say that you never read the same Mahabharata twice, because this most magnificent of epics comes wrapped in multiple layers, brimming with a multitude of perspectives -- and that’s before you even get to the minor players.

It is these minor players -- who flit on to the stage in brief cameos before disappearing – who have been given a voice by Karthika Nair’s

The narrators include the grand matriarch Satyavati, mother of Ved Vyasa, wife of Shantanu and stepmother of Bhishma (who took his terrible vow of celibacy to enable his aged father to satisfy his lust for the beautiful fisherwoman); Mohini; Amba/Shikhandi; the maid Poorna (mother of Vidur); Sauvali (mother of Yuyutsu, the illegitimate son of Dhritarashtra); the nameless wife of King Dhrupad, forced to watch her children being forged into weapons as part of their father’s obsessive quest for vengeance against Drona; Hidimbi and Ulupi (wives of Bhima and Krishna, respectively, who were impregnated and abandoned by their husbands); and Bhanumati, Duryodhana's wife.

Most, but not all, of the characters are women – the notable exceptions including two Padavits (humble foot soldiers). The two infantrymen are actually father and son, and their very divergent attitudes towards the war serve to book-end the narrative. Krishna makes an entrance to explain to Yuddhishtira why Aravan (Arjun's son from Ulupi) must be sacrificed to ensure the victory of the Pandavas. Aravan agrees but does not want to die a virgin. Since no woman is willing to marry someone who is certain to be killed the very next day, Krishna transforms himself into the luscious Mohini. And in a neat twist, as Mohini grieving for her slaughtered husband, hurls a curse at Krishna, 'O god that creates god that destroys god that forgets as gods so easily do."

The Krishna/Mohini dichotomy makes for one of the most memorable sections in the book, along with Sauvali’s wry observation that “When the King (Dhritarashtra) decides to rape me or my kind, we must not use the word rape”, and Dushala’s lament for her 100 slain brothers.

Most of us know the Kauravas as Duryodhana, Dushasana and 98 others, but Nair -- through Dushala -- names each one of them and turns a faceless, amorphous mass into individuals with distinct identities. It is an impressive effort, made all the more poignant by Dushala’s lines:

“Reduced to a number, a clan name.

That cannot be. They must be remembered. Mourned. Reclaimed.”

Interestingly, one of the most delightful narrators is not even a human; it’s a dog, Shunaka, who takes a decidedly dim view of the foibles of Homo Sapiens. When you consider the kind of brutality meted out routinely to other species in the Mahabharata (Arjun wiping out almost every living being in the Khandava forest, Janamejaya's sacrifice to wipe out all serpents to avenge his father's murder by Takshaka etc), you begin to develop some sympathy for Shunaka’s point of view.

A warning: This is not an easy book to read, especially if you like your myths racily retold. It can get slow, even ponderous at times. But those who persevere may well find the subtle, understated style and the gentle, ironic wit growing on them till they finally reach the end, replete with the satisfaction of having enjoyed a deeply satisfying, provocative work.

Vikas Singh is Assistant Executive Editor of The Times of India and author of Bhima: Man In The Shadow

Author : Karthika Nair

Publisher : Harper Collins India

Pages: 288

Price: Rs 399

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus famously observed that you never step into the same river twice. It would probably be just as accurate to say that you never read the same Mahabharata twice, because this most magnificent of epics comes wrapped in multiple layers, brimming with a multitude of perspectives -- and that’s before you even get to the minor players.

It is these minor players -- who flit on to the stage in brief cameos before disappearing – who have been given a voice by Karthika Nair’s

Until The Lions (the title is taken from the African proverb, “Until the lions get their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter”). Nair uses various poetic forms – rather appropriate, given that the original Mahabharata was itself written in shlokas – to offer a contrarian take that will make you see the familiar tale in a whole new light.

The narrators include the grand matriarch Satyavati, mother of Ved Vyasa, wife of Shantanu and stepmother of Bhishma (who took his terrible vow of celibacy to enable his aged father to satisfy his lust for the beautiful fisherwoman); Mohini; Amba/Shikhandi; the maid Poorna (mother of Vidur); Sauvali (mother of Yuyutsu, the illegitimate son of Dhritarashtra); the nameless wife of King Dhrupad, forced to watch her children being forged into weapons as part of their father’s obsessive quest for vengeance against Drona; Hidimbi and Ulupi (wives of Bhima and Krishna, respectively, who were impregnated and abandoned by their husbands); and Bhanumati, Duryodhana's wife.

Most, but not all, of the characters are women – the notable exceptions including two Padavits (humble foot soldiers). The two infantrymen are actually father and son, and their very divergent attitudes towards the war serve to book-end the narrative. Krishna makes an entrance to explain to Yuddhishtira why Aravan (Arjun's son from Ulupi) must be sacrificed to ensure the victory of the Pandavas. Aravan agrees but does not want to die a virgin. Since no woman is willing to marry someone who is certain to be killed the very next day, Krishna transforms himself into the luscious Mohini. And in a neat twist, as Mohini grieving for her slaughtered husband, hurls a curse at Krishna, 'O god that creates god that destroys god that forgets as gods so easily do."

The Krishna/Mohini dichotomy makes for one of the most memorable sections in the book, along with Sauvali’s wry observation that “When the King (Dhritarashtra) decides to rape me or my kind, we must not use the word rape”, and Dushala’s lament for her 100 slain brothers.

Most of us know the Kauravas as Duryodhana, Dushasana and 98 others, but Nair -- through Dushala -- names each one of them and turns a faceless, amorphous mass into individuals with distinct identities. It is an impressive effort, made all the more poignant by Dushala’s lines:

“Reduced to a number, a clan name.

That cannot be. They must be remembered. Mourned. Reclaimed.”

Interestingly, one of the most delightful narrators is not even a human; it’s a dog, Shunaka, who takes a decidedly dim view of the foibles of Homo Sapiens. When you consider the kind of brutality meted out routinely to other species in the Mahabharata (Arjun wiping out almost every living being in the Khandava forest, Janamejaya's sacrifice to wipe out all serpents to avenge his father's murder by Takshaka etc), you begin to develop some sympathy for Shunaka’s point of view.

A warning: This is not an easy book to read, especially if you like your myths racily retold. It can get slow, even ponderous at times. But those who persevere may well find the subtle, understated style and the gentle, ironic wit growing on them till they finally reach the end, replete with the satisfaction of having enjoyed a deeply satisfying, provocative work.

Vikas Singh is Assistant Executive Editor of The Times of India and author of Bhima: Man In The Shadow

End of Article

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA