Scraps of broken pottery from test pits dug by thousands of members of the public have revealed the devastating impact of the Black Death in England, not just in the years 1346 to 1351 when the epidemic ripped Europe apart, but for decades or even centuries afterwards.

The quantity of sherds of everyday domestic pottery - the most common of archaeological finds - is a good indicator of the human population because of its widespread daily use, and the ease with which it can be broken and thrown away. By digging standard-sized test pits, then counting and comparing the broken pottery by number and weight from different date levels, a pattern emerges of humans living on a particular site.

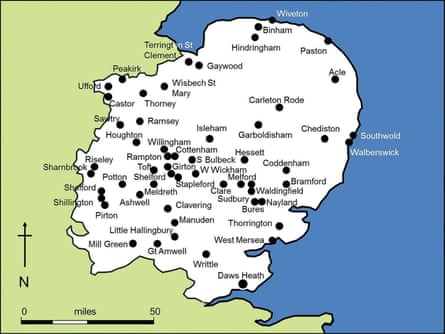

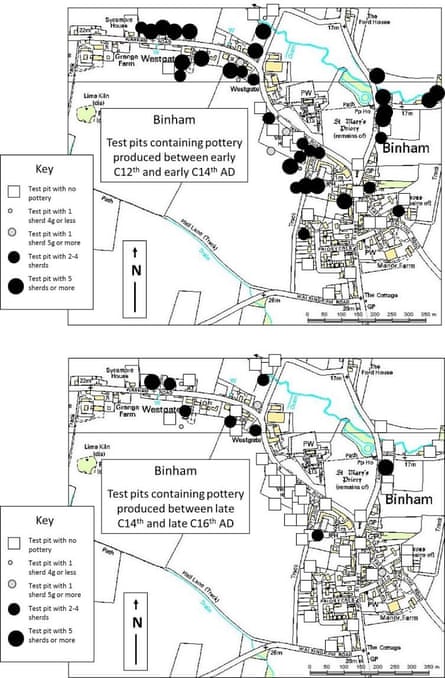

Professor Carenza Lewis has analysed of tens of thousands of bits of datable broken pottery, excavated from almost 2,000 test pits in eastern England. The sherds, taken from the levels relating to the periods before and after the Black Death, suggest a population collapse of around 45%. In some areas, such as Binham, north Norfolk, where there was a 71% fall in the amount of pottery, the figure is much worse.

Lewis, famous from her years on Time Team, now professor of public understanding of research at the University of Lincoln, has used the data to map the aftermath of the Black Death She reports her findings in next month’s Antiquity journal.

Lewis says that the devastation of the Black Death, regarded as exaggerated by some 20th century historians, was actually “on an eye-watering scale”. Its true extent, she believes, was masked by eventual post-medieval regrowth.

Since her volunteers excavated only in six eastern counties, at 55 currently occupied rural locations also known to have been 14th century settlements, she believes her figures may be conservative, missing many places where the population was completely wiped out and the area permanently abandoned.

Her analysis bears out the terrified contemporary accounts of people who lived through the epidemic and saw their world collapse around them. The impact on individual communities was catastrophic. At Cottenham in Cambridgeshire, where at least 33 out of 58 tenants died, “ruinous” houses were still being reported two centuries later.

Some 20th century historians had begun to question the scale of the epidemic, partly because relatively few plague pit burials have been found, but Lewis’s research bears out the most dire medieval accounts: overall her analysis across East Anglia illustrates an average decline of 44.7% in 90% of the settlements excavated. The pattern was uneven: Norfolk showed a 65% decline - up to 85% at Gaywood and Paston - far worse than Essex or Suffolk. Before the Black Death, Great Shelford in Cambridgeshire was a sprawling medieval village, stretching more than a kilometre along a high street and two greens: afterwards it was reduced to a single 200m row of houses beside the church.

The excavation of some 2,000 one square metre pits was carried out under archaeological supervision by volunteer members of the public, some of whom were literally digging in their back gardens. The technique could easily be applied to a further study across other English regions, and indeed across Europe, Lewis suggests.

Her paper ends on a sombre note. “This disease is still endemic in parts of today’s world, and could once again become a major killer, should resistance to the antibiotics now used to treat it spread amongst tomorrow’s bacteriological descendants of the fourteenth-century Yersinia pestis. We have been warned.”