Scores of public defenders outraged by the grand jury decisions not to indict the officers implicated in the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown briefly walked off their jobs in New York to stage a “die-in” on Wednesday to draw attention to the spate of recent deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of police.

Shortly before 10am, at least 200 attorneys streamed out of the criminal court building in Brooklyn chanting “I can’t breathe” and carrying signs that read “Black lives matter”. The public defenders say they staged the peaceful march and “die-in” to highlight the pervasiveness of racial inequality in the criminal justice system.

“This is something, honestly, that we’ve been battling for decades in terms of what we see as the unequal treatment of our clients,” said Deborah Wright, president of the local chapter of the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, which led the march. Garner, the Staten Island man who died in a police chokehold in July, was one of their clients. A grand jury recently declined to indict the officer, Daniel Pantaleo.

As they marched, those waiting in the wrap-around line to see a judge grabbed their phones to take photos and video. Some cheered and put their hands up in solidarity, while others wondered if the demonstration would cause delays.

Wright said that every attorney who participated did so in their free time, and those with appointments during the march did not leave.

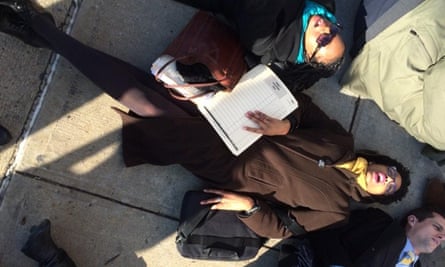

When the procession reached Atlantic Avenue, the protesters lay down on the pavement for seven minutes, the amount of time a bystander’s video shows Garner lay on the ground not breathing. For the final minute, the group fell silent.

As they continued their march more people joined, and some onlookers cheered them on. A group of young girls, some white and some black, started cheering and threw up their hands in solidarity.

Audrey Thomas, a private attorney and former prosecutor in Brooklyn, smiled brightly as they passed. “This is just so lovely,” she repeated and raised her hands.

Thomas said as a black woman she sympathizes with the protesters across the nation, but she said she also understands that law enforcement officers, who she worked with on cases for many years, have difficult jobs to do.

“The standard for a police officer who has risked his life and compromised his family obligations should not be the same as someone who is in the street committing crimes,” Thomas said.

She continued: “There should be a double standard, but it shouldn’t be one where one ends up dead and the other one gets praised. There has to be an appropriate middle ground where everyone can say, ‘you know what, justice was done.’”

The march wound its way back to the courthouse, where protesters chanted “I can’t breathe” 11 times, the number of times Garner gasped these final words while pinned to the ground in a police chokehold. When this finished, the lawyers dispersed and returned to work.

Getting louder as they make their way back to the court house #blacklivesmatter https://t.co/2UsWyd3obP

— Lauren Gambino (@LGamGam) December 17, 2014

The die-in was originally planned to take place inside the courthouse, to send the message that the entire system needs to be reformed. But on Tuesday night the Office of Court Administration barred them from holding the demonstration there.

“The inside of a courthouse is not a forum for demonstrations or protests,” said David Bookstaver, spokesman for the state courts.

“There had to be a spirit of cooperation here so that folks get to voice their opinions while not disrupting the institution where they work,” he added.

Some of the participants, however, were upset by the court’s decision not to let them protest.

“They shut us down,” said Amanda Jack, an attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services.

“It says a lot about the system and whose side the system at large is on. This is supposed to be the blind justice,” she said, gesturing to the courthouse behind her.

Several public defenders said they were marching for their clients who they say the justice system has failed, repeatedly.

“We know that people of color are doing jail time for offenses like hopping turnstiles while officers who kill unarmed men do not even see the inside of central bookings,” said Nora Carroll, a staff attorney with the Legal Aid Society in a statement.

For attorney Roslyn Morrison, the fight is also personal.

Morrison, who is black, said her seven-year-old son came home from school the other day and told her if he could have a superpower it would be to turn his skin white when he’s around police officers so that he and his friends wouldn’t be harassed.

“My heart stopped,” Morrison said. “I’ve had conversations about how I prepare him [to deal with police encounters]. But it really broke my heart to hear my son say that.”

She said she is hopeful that the protests, marches and die-ins will start a nationwide conversation about race relations and police brutality.

“I think the first step is knowledge and awareness, and the fact that people are out in this continued activity shows that this is just the beginning,” she said. “I think there’s an awareness that there hasn’t been before.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion