A massive coral bleaching event currently ravaging coral reefs across the globe could destroy thousands of square kilometres of coral cover forever, US government scientists have said.

In figures exclusively released to the Guardian, scientists from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) said about 12% of the world’s reefs have suffered bleaching in the last year. Just under half of these, an area of 12,000 sq km of coral, may be lost forever.

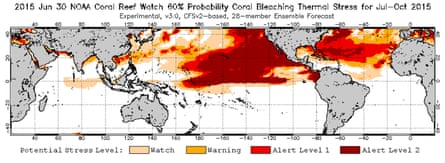

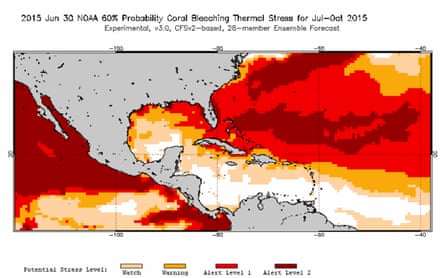

But the devastation is only getting started. The event could continue well into 2016. Noaa announced on Monday that the western Atlantic is about to heat up, turning the corals of the Caribbean bone white. When this occurs, bleaching will have hit every tropical ocean basin on Earth since June last year.

In all, scientists forecast a total of 15,000 sq km of reef may not recover and losses to the world’s remaining coral reefs would be a devastating 6%.

Dr Mark Eakin, the co-ordinator of Noaa’s Coral Reef Watch programme, said that given uncertainties around how long the event will continue it was very difficult to predict exactly how much reef would be wiped out.

“It probably won’t be as big as 1998, so we’re probably talking hopefully no more than 10%. Even if we’re talking one to 10% of the coral reefs around the world that’s a huge amount of coral reef area,” he said.

Global bleaching events have only been recorded twice before, in 1998 and 2010. Professor Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, director of the Global Change Institute at the University of Queensland, said Noaa’s figures, while rough, were decent estimates of the potential damage. He said, before 1998, bleaching of this magnitude had not occurred for “hundreds, if not thousands, of years”.

In 1998, a massive El Niño (an upwelling of warm water in the Pacific) set off a chain of warming events in oceans across the world that killed off 16-19% of the world’s coral reefs. Mark Eakin, the co-ordinator of Noaa’s Coral Reef Watch programme, said this year’s El Niño was playing a part, but “it’s almost certainly being driven largely by global warming”.

A huge patch of climate change-generated hot water, known as ‘the blob’, has been wobbling across the northern Pacific since this time last year. It first bathed the reefs of the Hawaii and the Marshall Islands in June 2014. It has now returned to where blitzed reefs have only just begun the slow process of rebuilding.

Other hot patches of water washed through the South Sea Islands during the southern Pacific summer. Reefs in the Indian Ocean were also hammered by warm temperatures.

“We are seeing real changes in the ocean as related to climate change,” said Eakin.

Corals can only tolerate a narrow range of temperatures. If the water around them warms by just 1C and this lasts more than a week, they are likely to bleach. After a mild warming event it is possible for polyps to regain their colour. But under extreme warming, the corals will die, meaning new colonies will have to grow.

“The recovery speed of these reefs, when you get a big bleaching event, is not a matter of a few years. It’s more on the scale of a decade or so,” said Eakin.

To establish the expected loss of coral from the current bleaching, Noaa used recent research from James Cook University, which found 40% of reefs in the Seychelles that were bleached in 1998 had now been replaced by weed and algae. Once this type of ‘regime change’ occurs, corals are unlikely to return.

Hoegh-Guldberg confirmed this “really high proportion” of lost corals was probably typical for massive bleaching events.

“The sorts of conditions we are facing are similar to 1998 and if it continues to develop we are going to lose coral again,” he said.

Hoegh-Guldberg said the background warming of climate change could also hamper recovery. After a warming event, corals that stayed stressed by even slightly warmer than normal temperatures recover more slowly.

“We’ve only had a 0.8C change in global temperature,” he said. “We’re already starting on a journey where just a mild change in temperature is causing a massive deduction in coral reefs. Just imagine when we get to 2C or 3C or 4C.”

In the Marshall Islands capital atoll of Majuro, where the Guardian observed massive bleaching last year, the first, fragile signs of a recovery have been found by scientist Karl Fellenius.

“Because the thermal event last July to December was severe, the coral colonies died right way. So the ‘bounce back’ would be new patches of coral on those clean skeletons, not recovery of those corals,” said Fellenius, who works on Majuro for the University of Hawaii Sea Grant programme.

“There are patches of new coral both on the lagoon side and ocean side of Majuro. Stuff is growing. But that’s like saying that 100 babies were born this year in the village, a ‘bounce back’ of sorts after 100,000 people died in a catastrophe last year,” he said.

But in dire news for the reefs in Majuro, and across much of the northern Pacific, the sea has begun to reheat.

“As of yesterday I see small patches of new bleaching on broccoli coral on the outer reef flat. That’s the first report [from the Marshall Islands] as far as I know,” said Fellenius.

Eakin said his models, which have predicted the passage of this event with remarkable accuracy, said the second wave of bleaching would also hit Hawaii and other Pacific island groups before moving into the Indian Ocean.

“This is two years in a row, and corals getting nailed in successive years like that are really going to take a beating,” he said.

This was the problem for corals worldwide as bleaching events piled one atop the other.

“The concern isn’t just about whether conditions are going to go back to normal, because we certainly expect they will. The question is how long does it take before they go back up to the really high temperatures that cause bleaching? That’s been coming much more frequently and in some areas its been getting much more intense,” he said.

There are stopgap measures that can greatly assist the chance of reef recovery for the time being. When a coral bleaches, it loses its ability to clean itself of algae. Once algae cover the surface, it is impossible for coral to repopulate. Herbivorous fish graze the coral and help keep it algae free. In polluted water, algae grow faster.

“Pollution and overfishing, if you’ve got a lot of that going on then coral reefs don’t recover very quickly. But if you can control those other factors you can improve the ability of corals to bounce back,” said Hoegh-Guldberg. Fellenius said he had asked the Marshall Islands government to enact temporary fishing closures during bleaching episodes.

But Hoegh-Guldberg, who in 1999 predicted the loss of most of the world’s coral reefs by the middle of this century, said the only hope for coral reefs to survive long term was rapid curbing of carbon emissions to stop the world from warming more than 2C.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion