It wasn’t always ‘us versus them’: a look back at Hongkongers’ attitudes towards mainland immigrants

Over the years, war, economic development and politics have all shaped locals’ opinions of newcomers to the city

From a warm welcome to discrimination, Hongkongers’ attitudes towards mainland immigrants have shifted over the years through war, economic development and political turmoil.

Following the second world war and up until the 1980s, waves of mainlanders flooded into the city and were welcomed with relatively open arms. The biggest occurred between 1949 and 1955, when several hundred mainlanders arrived every day, according to John Carroll, history professor at the University of Hong Kong.

“There was no real us versus them in that period. There were people fleeing a totalitarian regime – a lot of people felt sorry for them. They were willing to find ways to make the situation work,” Carroll said.

“By the mid to late 1950s, people started to realise [the migrants would stay long-term]. That’s when the government started to build resettlement estates.”

Economic and political changes also influenced attitudes over the years, according to Carroll, who said cheap labour from the mainland fueled Hong Kong’s economic expansion in the 1960s. Then, as China began to open up in the 1970s under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, Hongkongers started to feel a sense of pride in the mainland. And since Beijing had no authority over Hong Kong issues until 1997, the political situation was also completely different.

“Hong Kong’s economic boom had a lot to do with the availability of cheap labour and child labour,” Carroll said. “The backwardness of China was the modernity of Hong Kong.”

The backwardness of China was the modernity of Hong Kong

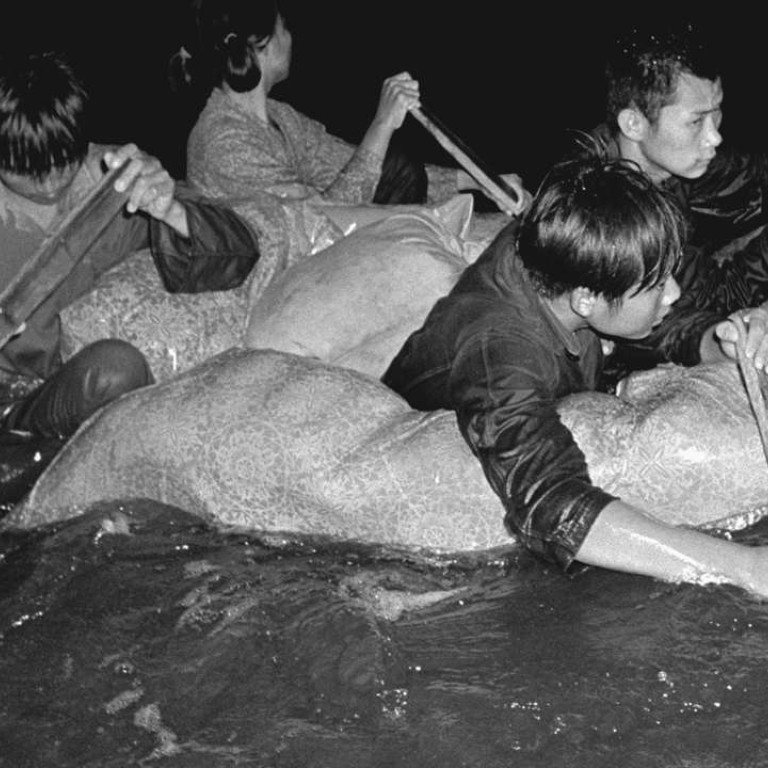

From 1974 to 1980, Hong Kong granted many illegal migrants the right to stay under the ‘touch base policy’ – a scheme that allowed those who made it to urban areas to remain in the city. This contrasts sharply with current immigration controls.

There are no concrete statistics showing how many mainlanders escaped to Hong Kong in that period. However, Yet Ho Pui-yin, history professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, estimated they accounted for 20 to 30 per cent of the city’s population growth from 1961 to 1981 when the population rose by about two million.

Ho said as people returned to the city after the Sino-Japanese war, almost everyone was considered a newcomer. And while there was less social inequality between locals and immigrants back then, many mainland immigrants now depend on social welfare and face financial difficulties, she added.

“There was no difference between locals and immigrants. They helped out each other,” she said.

A Chinese University of Hong Kong study, released Friday, illustrated current local attitudes. It showed people were concerned about mainlanders’ burden on social and economic resources. But with equal numbers of respondents critical of mainlander migration and accepting of it, the study concluded Hongkongers’ attitudes were not as negative as once thought.

The same cannot be said for mainlander perspectives. A survey of mainlander attitudes, released last year by the Education University of Hong Kong, showed 56 per cent of respondents felt discriminated against, 60 per cent felt locals were not tolerant of them, and 66 per cent felt locals had many misunderstandings and biases towards immigrants.