Interviewsand Articles

A Conversation with Zilong Wang: Medicine Journey

by Richard Whittaker, Feb 14, 2016

The quiet directness of Zilong Wang, his articulate, measured way of speaking and something so open about him makes an immediate impression. Who is this young man? If one is around Zilong very much at all, there’s soon no doubt that there’s something remarkable about him. As I got to know a little more about Zilong, I resolved very quickly to ask this young man for an interview before he left the Bay Area. I found it impossible not to think that what lay ahead for Zilong has promise for what I can only call the greater good.

He accepted my proposal for an interview and when we sat down together in my home to talk, Zilong was only a few days from embarking on a bicycle pilgrimage across the U.S. and to China and, ultimately, around the globe.

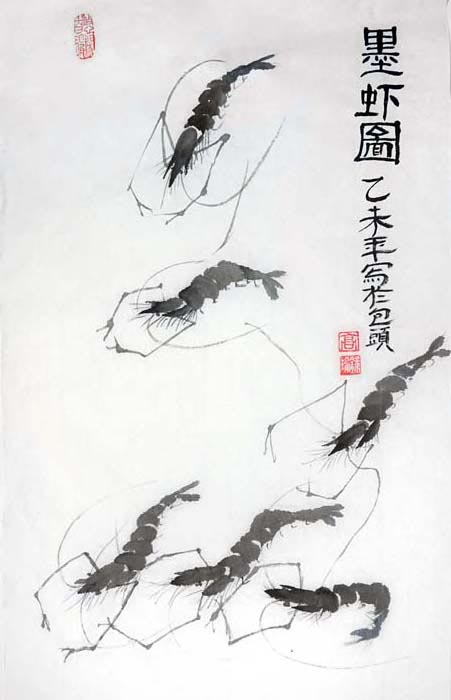

Richard Whittaker: You made a gift to me of this beautiful ink drawing that your grandmother did. Tell me something about your grandmother.

Zilong Wang: She’s the mother of my father. She ‘s in her late ‘70s. Her entire career was in this factory in Inner Mongolia as a technician who draws the graphs and measurements for the military tank.

RW: For the Chinese military?

Zilong: Exactly. My grandfather was a tank engineer in the same factory. That’s how they met. They’re the early generations when they had the freedom to date, instead of having an arranged marriage.

RW: I see—not under the formal, arranged marriage, way of doing things.

Zilong: Exactly. But they had to go the party secretary to be authorized to go on a date. The party secretary would look at the two families’ background to make sure they’re not landlords or capitalists or revisionists [laughs].

RW: I see.

Zilong: When they decide both sides are Red enough they can go on a date.

RW: So what era would this be—was this during the Maoist Revolution?

Zilong: Yes, 1950, I think.

RW: So the revolution is well under way by the 1950s.

Zilong: Exactly.

RW: You missed it.

Zilong: I missed it, and my parents were born just at the start of the Cultural Revolution.

RW: Were you close to your grandparents?

Zilong: Yes. They lived with us for a few years.

RW: Did they talk about the revolution?

Zilong: No. And it never occurred to me to ask. I actually never knew about it in any way or form until I left China. It’s only in recent trips when I went back to China that I asked them about the revolution, how it was for them, and I did a recording to preserve it for posterity.

RW: What stands out in their story, if you would be willing to share it?

Zilong: It just gives me so much gratitude for the strength of their values. They have so much integrity and principals, sometimes to their own apparent disadvantage at that time. And I see that, later on, when the craziness of the political fervor passed, that people respected them very much, and respected their children. So this karma became visible in a very tangible way—this intergenerational karma that’s passed on, in this case, in a good way.

RW: Yes. Your grandparents. And your parents were children during the Cultural Revolution?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: Have they shared memories of that with you?

Zilong: Yes. They were never persecuted because both sides of the grandparents, they are very just hardworking, devoted, and they didn’t get involved in a lot of leadership struggle.

RW: So they were spared some of the difficulties?

Zilong: Yes. My parents mostly have very sweet childhood memories of the whole family, with all the kids, sharing one piece of candy. Just the absolute scarcity of material resources. How much joy they still have in their childhood.

RW: What a dramatic story.

Zilong: For them, those are some of their sweetest memories, and when my parents told me about their childhood, there’s no bitterness about it, because they didn’t know there was any other way. It’s just how everybody lived.

RW: How many children in your family?

Zilong: I am an only child. My dad is one of four siblings. My mom is one of five.

RW: Are you a result of the one child policy?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: Do you have any reflections on that?

Zilong: Because it is also the only reality that I knew growing up—all my peers are all single child as well—it didn’t strike me as odd. But now looking back—having seen so many American families that have siblings—I see it. Collectively, there was even a diagnosis of this single child: emperor-little princess—a whole generation for a 30-year span, we didn’t grow up knowing how to share. We got the full attention of both parents—so much expectation, we are it.

RW: Yes. As a child, you wouldn’t know anything different; it’s always the case with children. But now you can see the pressures, all the hopes and responsibilities are placed on one child.

Zilong: Yes. Also making the parents a lot more risk-averse with what to do with this one child. It makes the cost of losing the child a lot higher.

RW: My God, yes. How did you end up sitting at this table talking with me? You’re in Oakland, California; you’ve come a long, long way from China. And given that you’re the only child, I mean there must be quite a journey in getting here.

Zilong: Here is my journey every step of the way, looking back. I grew up until the age of 17, in China. Then I went to Germany for my last year of high school as an exchange student to avoid the notorious cramming for the college entrance examination; for a whole year in China you just drill on test taking. So instead, I spent that year in Germany getting to know a different culture, also knowing that I will want to come to the U.S. for college. My mom in particular, planted that seed in me.

RW: I see.

Zilong: She always wanted to see the world. She has this childlike, expansive curiosity about the world, and wanted her son to have the opportunity.

RW: That’s not so risk-averse, is it?

Zilong: I feel that my parents are unique among their generation. So much of who I am, I owe deep gratitude to them.

RW: Absolutely. I’m touched by just this much of your story. Of course, all of us have to be grateful to our parents, but your story is somehow very strong with that. I take it that in that the last year of high school, and the results of that test—I mean, it charts the rest of your life. Right?

Zilong: Exactly. It’s actually the 18 years before that you are preparing for this test, and the 60 years after that is determined by this test, to a great extent. For most people.

RW: So you did a kind of…

Zilong: Bypass.

RW: Bypass. You spent a year in Germany. Had you already learned German?

Zilong: A little bit; some basic German for going there. Once in Germany, picking up the language came very fast, because how similar German is to English. And also, I love languages and love imitating sound, even as a child. So that came naturally.

RW: How many languages do you speak?

Zilong: Just Mandarin, English, and German.

RW: You must speak German pretty well, I would guess.

Zilong: By the time I left Germany, I was pretty fluent. Right now, I have forgotten a lot. But every time I go to a ten-day meditation retreat, my German improves dramatically.

RW: That’s fascinating.

Zilong: I talk to myself in German and words that I have long forgotten, sophisticated vocabulary and syntax, all come back while I’m in ten days of silence.

I think it’s like the acquired savant—like when a brain trauma activates some kind of special power. Some people, when they have a brain injury, suddenly they start to play piano. I think 10-day meditation is similar where the vow of silence shuts off my dominant language. So German emerges.

RW: How very interesting. What were the important things for you in your year in Germany?

Zilong: The German culture left a very deep impact on me. Just how direct, matter-of-fact, and all the German stereotypes we have of how punctual, how precise. It really went into my bones, and I find it very compatible. That’s perhaps why I was drawn to go to Germany in the first place.

RW: So you found that those German stereotypes were true in some ways in the German people?

Zilong: Yes, about the work ethic and the temperament; there’s something very endearing.

RW: Exacting?

Zilong: Yes. And very matter-of-fact and diligent. It is quite a contrast to contemporary Chinese culture. In Chinese culture, everything is very circumvent; what you say never really means its face value.

RW: I see.

Zilong: And there is so much cutting corners, and just not giving it the full—in almost a rush to get things done. Instead of taking the time like the craftsman.

RW: Giving everything its due.

Zilong: Exactly.

RW: Not going to the next step until step one is done right and then step two is done right.

Zilong: Yes.

RW: You alluded to some aspects of the German culture that felt compatible with Chinese. Did I hear that right?

Zilong: Yes. I thought it was compatible with my personality.

RW: With your personality.

Zilong: Yes. I see the past seven years of my life moving from Shanghai to Germany, then to the East Coast of the U.S. and then to the West Coast—it’s like a journey to the West in pursuit of reason, logic, and knowledge. Part of that is I’m driven by the admiration of the West’s success. I want to learn about that so China can also benefit from it. And in many ways, Germany—or the German culture and philosophy—hold the keys to the Western mind.

RW: That’s very interesting and I’d like to know how you see that

.

Zilong: For example, the modern university system was created in Germany, and Japan modeled its university system after Germany. Like with the enterprise of science, and also at a more metaphysical level, the way of thinking, the mindset, the philosophers that influence Western culture are German, for example, Karl Marx and Hegel.

RW: Have you studied Marx and Hegel?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: My little dusting of knowledge about those two is that Marx was much influenced by Hegel who saw the march of history as the story of the spirit entering the world somehow and realizing itself. Would that line-up with your sense of Hegel?

Zilong: Yes. The bit about Hegel that I know is through reading Marx. I think of Marx’s famous saying, “The economic foundation determines the superstructure in the mindset.” So the material foundation determines the mind. The world is material and everything, culture, et cetera, functions from the material.

RW: Have you any other philosophers that you have looked into that you feel are important in that regard?

Zilong: During college, essentially, I did a broad survey of the philosophers. All of them, I think, share the German philosophers; they rely on reason, on logic, on deductive thinking. And I think that is the trademark, at least in a simplified way, of the Western way of mind.

RW: Yes. I think of Descartes around this, who was French, and his famous cogito ergo sum— “I think, therefore I am.” He’s a big figure in this whole thing about the trust we place the power of our mental function, our thinking process.

Zilong: Yes.

RW: But it’s interesting to me because when I think of German philosophy, I think of a lot of reaching toward the non-material or the spiritual. There’s Hegel, with his Phenomenology of the Spirit, and then Kant, who was saying we can’t know things in themselves. But Kant takes us right up to the edge of the noumenal and maybe leaves us with something like a hunger for it. And then there’s Heidegger with his focus on Being. And there are a number of others German philosophers who aspired to approach things beyond our the realm of ordinary thought.

Zilong: Yes. It seems like, at the edge of reason, they always almost tumble into a world that’s mystical

RW: Yes. Nice way of putting it. Do you have any feeling for that?

Zilong: Yes. And even in the natural sciences, be it biology or physics, at the edges they’re increasingly cracking this façade of what we think is the material world where there’s a glimpse of mystical light shining through.

RW: Yes. Are you interested in that?—let’s say, the territory where the structure of logic, and the rational mind reaches the end of what it can do.

Zilong: Yes, very much so. And at, I think, the third year of college it caused an existential crisis for me—depression. Because during college, I spent a lot of time studying reason and logic, and as you go into the advanced logic courses you learn about incompatibilities and incompleteness, and the famous incompleteness theorem of Gödel, which essentially proves that at the edges of reasoning it collapses on itself. Or maybe the greatest triumph of human reasoning is to show that it’s not at all reasonable.

It completely threw me off. I said, “Wow. I spent three years training my brain to be a reasoning machine, thinking this is it—this is what made the West great.” Now at the advanced level of inquiry, it’s actually saying this is not it; this is ridiculous, by its own standard.

RW: Can you say more about your crisis there? What was happening and how did that go for you?

Zilong: It’s like if I’d thought reason was the only real thing I could hang on to, and apparently reason has proved itself to be unreasonable, what am I left with? And at the same time, seeing how, with some seemingly innocent assumptions, we have created all the suffering in the world.

It seems like—both by the inherent internal logical consistency and its outside effect—reason, at least by itself, is not something to be trusted. So what’s next? What else have we got? And I knew that question provided the opening to the much greater dimensions of reality and knowing.

RW: But that was a hard period?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: Is it okay that we talk about this?

Zilong: Yes..

RW: Okay. How long would you say you wrestled with this?

Zilong: It probably lasted half-a-year to a year during my third year in college.

RW: I see.

Zilong: I was almost having problems sleeping. Because the brain had become a calculating machine running on autopilot, and I had lost control of it. It wouldn’t stop.

RW: What help came to you?

Zilong: For three of the four years in college, I lived with three Tibetan monks in the same dorm. The dorm is six-room, like a house.

RW: Yes.

Zilong: They were sent by the Dalai Lama to study Western humanities at Hampshire College. And for some reason, I had no idea of Buddhism, or Tibetan Buddhism. But I just was so tired of living with 18-year-olds who smoked pot a lot, and played a lot of music at night, so I just volunteered to live with the monks and to be their guide on campus, because their English was not yet fluent.

RW: Right.

Zilong: They never preached to me or tried to convert me, but just being in their presence, I think slowly melted the hard ice.

RW: Did you ever get into discussions with them where you asked them questions?

Zilong: Yes. I would ask them what are some meditations that would help me to fall asleep. And I hosted a campus activity for them to teach meditation, and just to share about their three-year silent retreat, et cetera. But I was doing it because I was just curious. There wasn’t any religious or spiritual aspect to it.

RW: Right.

Zilong: But now, looking back, that really planted a seed. And these three monks are very high monks. They are all head of monasteries in different parts of the world and go on world tours giving teachings. But I never knew that. They were just my housemates. I just saw them as human beings. And that untinted, unfiltered, raw experience of living with them, I think, was a deep blessing.

RW: As I listen to you I have the sense of something being deposited in you. Does that seem like a good description?

Zilong: Yes, yes.

RW: What good fortune.

Zilong: Yes.

RW: What was it again that moved to ask to live with them?

Zilong: I think the other options made it easy. I don’t want to live with 18-year-old, American kid.

RW: Okay. So you finish your college years. And what was your major?

Zilong: Hampshire College doesn’t have majors; I have to create my own concentration.

RW: I see.

Zilong: The concentration I created is logic of nature versus logic of capital; reading of Marx and Darwin. So that was the theoretical part of the thesis.

RW: And you graduated when?

Zilong: The summer of 2013, almost three years ago.

RW: Just three years out. My goodness! Am I right in remembering that you rode your bicycle across the country?

Zilong: Yes. It was right after I graduated, and I started from the college. I rode all the way to San Francisco. So from Western Massachusetts across the country.

RW: Wow. How long did that take you?

Zilong: Two-and-a-half months.

RW: Would you tell me a little bit about that?

Zilong: Yes. It was a very formative experience. I wanted to do that because I felt like I had been in ivory tower for all my life; I have been in this liberal, leftist bubble in Western Massachusetts for four years. I wanted to know the broader spectrum of the human experience, and also of America—the real America.

RW: Yes.

Zilong: Two other Hampshire graduates did the bike tour two years before, so that gave me the idea. So I just prepared, not really a lot; I had no experience biking. I know how to ride a bike, but I am not a cyclist of any sort. The longest I rode a bike before going on the biking journey was for two hours.

RW: How did that work for you?

Zilong: The first few days was painful because it started to climb immediately. And one of the exercises is to not use money to buy lodging. So every night I would knock on the door of strangers to ask if I could camp in their backyard. And throughout that entire two-and-a-half months, every single night I was able to find someone who says, “Come in.”

RW: That’s amazing. Every night you knocked on the door of a stranger?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: That takes some courage. Tell me some of your experiences with that.

Zilong: The statistics overall was that one in five of the doors that I knock on, I would get a “yes.” Sometimes I would get lucky; the first door I knock on would work. There was one day when I think I knocked on over ten doors and it was the eleventh door that I knocked on that finally they say, “yes.” And with each one who let me in, I have showered every night in someone’s private bathroom.

RW: Oh, my gosh.

Zilong: Because once they let me in, we started chatting and clearly, after riding in the hot sun for the whole day, I was in need of a shower. I have never showered that consistently in my life, every night for two-and-a-half months. And with the whole spectrum from Christian fundamentalists and Mormons, Republicans, to hippies—just the whole spectrum. They all welcomed me with open heart, and just restored my faith in humanity.

RW: That’s beautiful to hear.

Zilong: And throughout the entire trip, I never locked my bike once, and I encountered zero bad persons, not even a harsh word

.

RW: It’s amazing.

Zilong: So it really affirms the goodness of people.

RW: When you came out here, did you know what you were going to do when you got here?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: What was that?

Zilong: I came out here to start an internship at a sustainability consulting company. And I worked in the company for a little over two years—so for my entire time here, until I quit my job last October.

RW: Tell me a little bit about this company.

Zilong: The company is called Blu Skye. It’s a management consulting company, a boutique firm, small, 10 to 20 people that specialize in corporate environmental sustainability.

I wanted to do something that has meaning, that’s good for the earth, good for the world—and also, I wanted to know the business world. So that seemed a perfect place where I could be exposed to both sides.

RW: So what did you learn?

Zilong: I learned that as Einstein said, “We cannot solve the problem at the same level of consciousness that created the problem in the first place.”

I learned that there are people that do not have evil intent, those people in the corporations. Even at Monsanto and Wal-Mart, JP Morgan, Chase, they do not have bad intent. They are doing their best to play by the rules of the game, and the rules of the game are beyond the power of even the most powerful CEO, even all of them together, to change. It’s not a business problem, I think it’s a civilization problem.

RW: Yes.

Zilong: That’s why I decided to leave that world, because during that work, people would pat me on the back and say, “Good. You’re doing work to save the environment.” But I know very well we’re just rearranging the chairs on the deck of Titanic.

RW: At this point, what is clear for you and what isn’t clear?

Zilong: Yesterday, I heard Guri [Mehta] quoting Gandhi that, “Anything that you do is insignificant. But it’s absolutely essential that you do it.”

We’re at the edge of an evolutionary leap of human consciousness in this round of high complex life form on Earth. Humans are at the point of making that leap. Statistically, the odds are not good, just looking at how many rounds of complex societies have collapsed. Even within the human form and on this planet, how many rounds that have gone down. There’s no guarantee and the odds are not good, but I am just so inspired by people who are holding seeds of that truth and are living it. It gives me great hope that it doesn’t really matter what the outcome is, because there’s no way we can predict it. Change is not linear, and the best I can do is to try to tap into and cultivate that light and live it.

Even in the very awkward and primitive days of me trying this, the results, the response from the Universe has been incredible. That just blows me away. So I, for now, don’t know of a better way to spend time on Earth.

RW: That’s beautiful. And you’re leaving soon. Right?

Zilong: Yes, end of February [in two weeks].

RW: When you leave, what are you going to do?

Zilong: The current plan is to go on a pilgrimage eastward bicycling from the U.S. to China. But depending on the visa situation and the geopolitical safety situation, I might have to adapt the route. The current plan is to go around the globe once. But I won’t let that be the end in itself. I’ll remain open to the spirit of the pilgrimage. It’s in service of the ecological and spiritual awakening of our time.

RW: Are you going to be in touch with people and making reports, that sort of thing?

Zilong: Yes. When I decided to go on this pilgrimage, one of the first persons I talked to was Guri. She asked me to sit with two questions: why am I doing this? And, how is it service to something more than myself?

So I see that reporting and sharing as an important way of service so that it’s not just me enjoying the learnings.

RW: Are you in touch with your parents?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: How are they holding up?

Zilong: The first time, when I first told them the news that I’m going to quit my job and do this, they got a little upset and raised their voice, essentially saying, you don’t really know what you’re doing. You’re throwing away all that and doing some wacky thing. We were on a Skype call. I had to hang up and say, “Dad, I’m going to call back in a few minutes.” And I just cried for two minutes and then called back. But surprisingly, in two or three weeks, they have completely turned around, and increasingly, now they are my strongest support.

RW: That’s amazing; that’s wonderful.

Zilong: So I feel very blessed. I don’t know of many Chinese parents, especially if have only one child…

RW: This is pretty special.

Zilong: And they also resonate with the mission. They both say that this is the most meaningful work to do.

RW: That’s beautiful. Brenda Louie told me the Chinese people are not religious. I had asked her about a title for a series of her paintings: Flowers from the Sky. I asked, “what do you mean by title?” She said that in China, we’re not religious, but we feel the sky and the earth. Sunlight comes from the sky. The rain comes from the sky; these are blessings that come from above and fall on everyone—rich and poor, good and bad.

She was trying to tell me that there’s a kind of philosophical or mythic way that the Chinese regard nature that may be a spiritual way of looking at nature and life. Does this make any sense to you, what I’m saying?

Zilong: It all rings a bell. I think what she said about China not being religious, it’s the impression of many people. And also, China is so vast. But we have contemporaries, like Master Hua, who you know about, and Mao. They’re both Chinese.

RW: Yes, that’s right. Master Hua was the Reverend Heng Sure’s teacher[Buddhist].

Zilong: That’s right. So I would hesitate to make a generalization. But any culture that can survive for that long, there must be a very vibrant, perhaps under the radar, spirituality.

RW: I think of Confucius, and Taoism. Are you a student of Taoism at all? Is that alive in China today?

Zilong: I think it is alive, and I have actually memorized the Tao Te Ching.

RW: Really?

Zilong: It’s short. It’s 5,000 words, that’s why I picked it for memorization.

RW: But that’s amazing. You’ve got it in memory?

Zilong: Yes.

RW: The way that can be named is not the way.

Zilong: Yes.

RW: And Brenda Louie talked about Mencius. The part that interested her the most is that Mencius viewed people as having good hearts, fundamentally. Do you know Mencius at all?

Zilong: I have not read Mencius entirely, but I picked up his famous quotes over the years.

RW: Taoism appeared here in the ‘60s, and the I Ching. Are you familiar with it?

Zilong: I have stayed away from I Ching because even Confucius said he only dared to start reading I Ching at the age of 50. It’s beyond me, at this point. I have a glimpse of it.

RW: When I was around your age I moved to San Francisco. In the middle of the ‘60s, there was a tremendous thing going on here. The I Ching was a popular book in those days. Eastern religion was coming to the West in a big way. Do you have any feeling for the Chinese treatment of the Tibetans? I don’t want to get you in trouble.

Zilong: No worries. When I was living with the three Tibetan monks, we became very good friends, and sometimes I think they forgot I am Chinese. I would come into the living room and it was during the time when there was a surge of the monks self-immolation. And the monks were just telling me, just with a heavy heart, “There ar two more.” “There is one more.” “Now it’s 99.” “Now there’s 104.” And at the same time, a lot of young Chinese—even middle-aged officials, businessmen—they have become very fascinated by Tibetan Buddhism. They have become disciples.

RW: Fascinating.

Zilong: So I feel this is the collective karma, what China has done. If there is such thing as China, what it has done to Tibet, or to other cultures within itself, is its collective karma and there will be consequences. And I feel weight.

Also what happened to Tibetans is not unique. The Chinese are doing this to Chinese at ten times the severity. Just all the historical temples that are destroyed. It has taken on an ethnic dimension between China and Tibet, but I think the bigger picture is just what this madness is doing to the society itself.

The destruction of Chinese culture, the suffering of Chinese people is just—they have inflicted it upon their own ethnicity. It’s the same as they have inflicted on others. So it’s the three poisons—the greed, hatred, and delusion—acting itself out and taking on different dimensions. Sometimes it takes on ethnic dimension, sometimes it takes on a political dimension.

RW: Yes. A lot of Tibetans have left Tibet and many of their sacred documents have been brought to the West. It curious that the materialistic culture that we have here has become a refuge in this way, a place of safety, for some of the spiritual riches of the East. I forgot how you put it, but we’re not going to get a lot more chances. I mean, it seems like we’re getting into some critical areas where if some things don’t go in a certain way, it’s going to be catastrophic.

Zilong: I’m also seeing our era is almost the rise of dharma in the West, and the gospel is spreading in the East.

RW: Interesting.

Zilong: It’s almost a millennial swap. China now has over 100 million Christians. We will soon become the country that has the most number of Christians in the world.

RW: That’s amazing.

Zilong: My mom is being pulled by many friends to attend this church—just among the Shanghai urban cosmopolitans—because people are so hungry for meaning and salvation. And Jesus said, “A prophet is not without honor, except in his own hometown.”

The traditional religions can’t do it for people anymore, because people have seen the corruption behind it. And this Western religion, Christianity, is fresh energy; it has filled the vacuum.

RW: That's really interesting.

Zilong: In the West, as you mentioned, the ‘60s and ‘70s saw the corruption of the church and the fascination of the mysticism of the East. The dharma is really spreading in the West.

RW: And Buddhism, in particular, has become powerful here. It seems compatible with our scientific materialism—I mean, in the sense that you don’t have to look for something supernatural. Buddhism is just asking you to become present, and to become aware.

Zilong: Yes. I have hope that the East and West will meet each other at the heart level through this taking of each other’s medicine.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Feb 14, 2017 Louisa Cardinali wrote:

Thank you Zilong for sharing your pilgrimage with Richard! I found it very touching and informative and healing! Yes, as Georgina before said, it reminded me of the Peace Pilgrim but a spiritual equivalent for today! Many wise works to ponder and contemplate on and learn to live with. May spirit of heart and awareness guide you on the journeyOn Feb 10, 2017 Jim Adams wrote:

Do you know if Zilong Wang is going to be biking west to east through Missouri? From Pleasant Hill, MO., just outside Kansas City on Rock Island Trail to Windsor, MO, then pick up the Katy Trail that goes all the way to St. Charles, MO. just outside St. Louis. I live in St. Louis, and would love to join Zilong for a day or two if he is taking this route back east.On Oct 6, 2016 Georgina Galanis wrote:

A very enriching story captured by the sensitive inquiry of Mr Whittaker….encompasses respect for ancestral passages, generational sufferings, cross cultural connections beyond borders, youth and the aspiration for peace ….one person's personal power unfolding through the dark night of the soul and every obstacle … This reminds me of the supreme work of Peace Pilgrim, Mildred Lisette Norman…non denominational spiritual seeker ….in a way, seeking an authentic evolution without any preparation, a truly humbling way to live through the heart. It is always moving, to hear of people that will risk what should be done for what may be done in order to create new role models with experiences beyond the norm that show a new consciousness evolution for humanity. Zilong's story is a connecting thread from the past, into a future now unknown..and overflowing with hope in action. Thank you for sharing this medicine.."Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love. "

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. from "Where Do We Go From Here?, " Delivered at the 11th Annual SCLC Convention in Atlanta, Georgia, 16 August 1967.

On Oct 6, 2016 Carol Kilby wrote:

what a terrific revelation of how culture evolves. I end hopeful that this "taking of each other's medicine is part of the evolution of consciousness of our species and so called civilization,On Oct 5, 2016 Smrraub wrote:

Beautiful. Thank you!On Oct 5, 2016 Ram wrote:

Beautiful! Thank you, Zilong and Richard!On Oct 5, 2016 Half Slow wrote:

A glimpse of fragility that moves boulders. Thank you.On Oct 5, 2016 Micky O'Toole wrote:

Zilong is one of my favorite people in the world. I had the privilege of getting to know him during a Laddership program last fall. This is a beautiful and inspiring conversation. Thank you Zilong and Richard! ♥On Oct 5, 2016 Eroca wrote:

Absolutely fascinating, the journey this young man is on! He is a loving agent of change, and much needed on this planet.. May he remain safe, and curious, and full of loving kindness.On Oct 5, 2016 Sidonie Grace wrote:

Wow!!! I'm speechless! Simply remarkable. Thank you both. Namasté & Godspeed!On Oct 5, 2016 Bela wrote:

Wonderful gems captured here that will sink in throughout my day. Thank you both for this awakening read.On Oct 5, 2016 Regina wrote:

Articulating high level awareness with grace.On Oct 5, 2016 Joy wrote:

Thanks for this. We get caught in our personal world events and they define our life. This interview provides a respite, a breath and a chance for another perspective.On Oct 5, 2016 han wrote:

it is a big disappointment, reading the article, see the image of the guy BUT I can't see the drawing of his grandmother, there must be a way to show readers all over the world also that !Please keep in mind that in the future articles it should be complete ! attached together the drawings when it is mentioned in the story !

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ATTENTION