The Secret Christians of Brooklyn

At St. Lydia’s church, every service is a dinner party, and believing in Jesus is counter-cultural.

“A friend of mine [had] come to worship once or twice, and somebody said to her, ‘Oh, St. Lydia’s, that’s like the hipster church,’” Pastor Emily Scott laughed. “She was like, ‘That’s not what I just went to at all.’ It really doesn’t come across as a place where cool people hang out.”

You’d be forgiven for assuming that St. Lydia’s, tucked into the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn, is a church for hipsters. The 1,000-square-foot congregation is a co-working space for freelancers by day. The regular Sunday and Monday night services are staged as dinner parties. By Scott’s own description, a lot of early career writers and creative types attend, and the church actively draws on the “beauty culture” of Brooklyn.

But much of what happens at dinner church is counter-cultural, Scott argued in a phone interview. For one thing, there aren’t many places in New York where people can have dinner parties—only the rich people tend to have apartments that can fit multi-leaf dining-room tables. The environment is designed to be the opposite of the typical, anonymous New York experience, full of jammed subway rides and crowded streets, she said.

But most of all, it’s hyper earnest. “We are a space that is very sincere, and we’re not snarky, and nobody is playing like a too-cool-for-school competition,” Scott said. “That’s kind of a huge reality of a younger person in a place like Brooklyn. There is a kind of game people play about who measures up and how. … It can be a painful experience, trying to navigate that sort of world.”

Although the congregation tends to be a bit younger than most mainline churches, all sorts show up for dinner, Scott said. A few homeless folks regularly attend, along with a woman who lives in a nursing home and a retired heating-and-cooling engineer from Westchester. With only a few dozen people in attendance at each service, this makes a difference.

“It can be like friends hanging out together, but it can also be very awkward—because there are awkward people there, [or] there can be people who don’t know each other, and they’re negotiating what to ask the person next to them,” Scott said.

Awkward dinner table conversations definitely aren’t cool. But that’s a good thing, she added. “I don’t think that’s our main goal as Christians, to be comfortable all the time.”

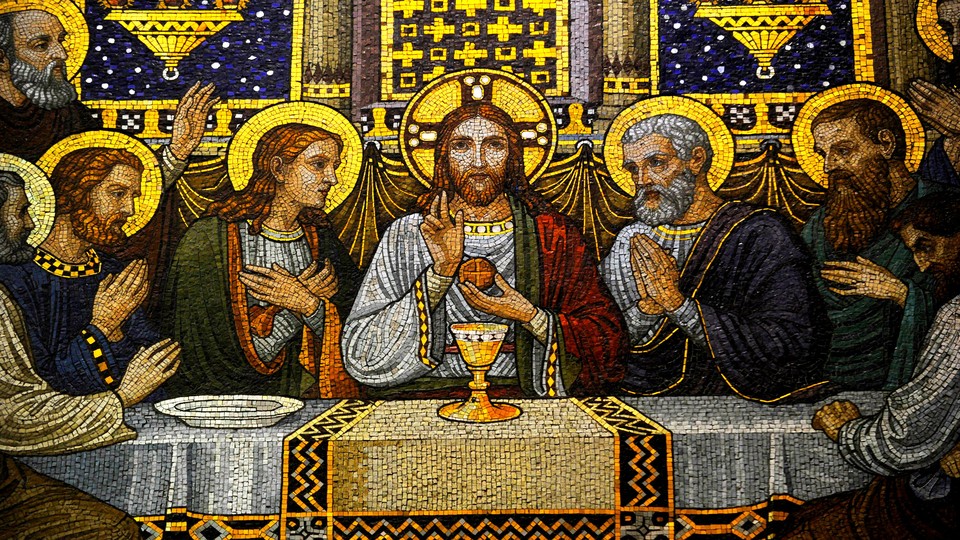

As much as St. Lydia’s might not look like a typical service at the Lutheran and Episcopal dioceses it gets funding from, it’s definitely not a Unitarian church. “We’re very Biblically grounded,” Scott said. “A lot of the year is telling stories about Jesus, and talking about what Jesus said.” The service is designed to emulate the worship of early Christians, which was often centered around meals. The bread—homemade from a local bakery, of course—serves as the eucharist.

Yet as culturally defiant as St. Lydia's might be, Scott said, it can be a struggle to be publicly Christian in Brooklyn. She’s talking about a specific class of the neighborhood, of course—historically, the borough has had vibrant Jewish and Catholic communities, and still does today. It also has a rich Protestant history: In the nineteenth century, it was known as “the city of churches,” and was home to some of America’s most famous Congregationalist clergymen. But in today’s young, progressive, creative-class circles, “all of those cultural connotations of what a Christian is ... are totally negative,” Scott said. “I’ve definitely heard that they find themselves censoring themselves when they talk with friends about going to church. … For some of them, posting about St. Lydia’s on Facebook for the first time was like a really big deal.”

There’s an element of self-hatred in this. “I’ll say, ‘I’m a pastor, but my church isn’t weird. I’m not from a scary church.’” It’s a joke, but it’s also a tacit acceptance of certain stereotypes about American Christians, most of which are probably unfair. The worry among congregants, she said, “is that people will think I’m conservative, people will think I hate gay people, people will think that I’m judging them, people will think I’m better than them.”

It’s an interesting irony: In New York City, anyone can be anything they want, as long as they’re not part of the culture that the majority of Americans share. Luckily, that’s why Scott preaches grace. It’s “the idea that God comes and finds us, no matter where we are,” she said—even if you live in Brooklyn.