The Weird Familiarity of 100-Year-Old Feminism Memes

A century ago, widely circulated images and cartoons helped drive the debate about whether women should have the right to vote.

It seems almost farcical that the 2016 presidential campaign has become a referendum on misogyny at a moment when the United States is poised to elect its first woman president.

Not that this is surprising, exactly.

There’s a long tradition of politics clashing spectacularly with perceived gender norms around election time, and the stakes often seem highest when women are about to make history.

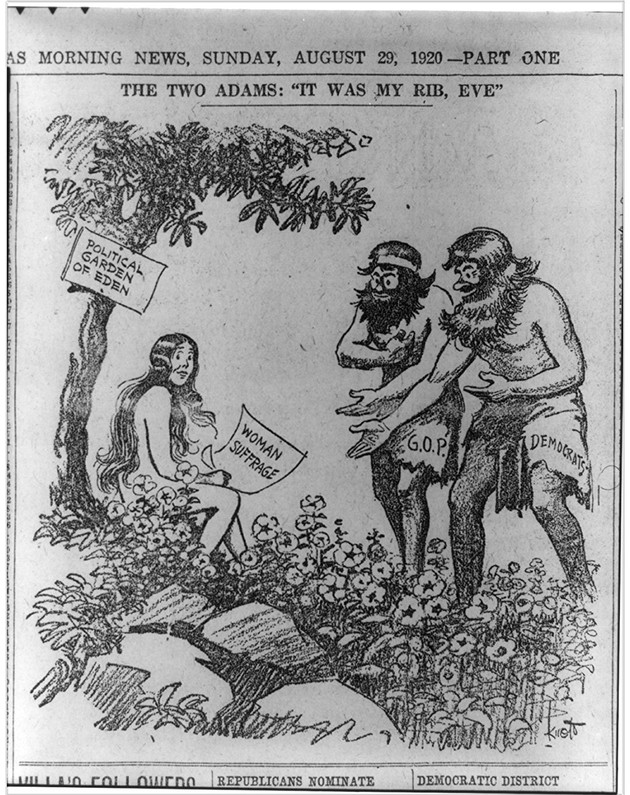

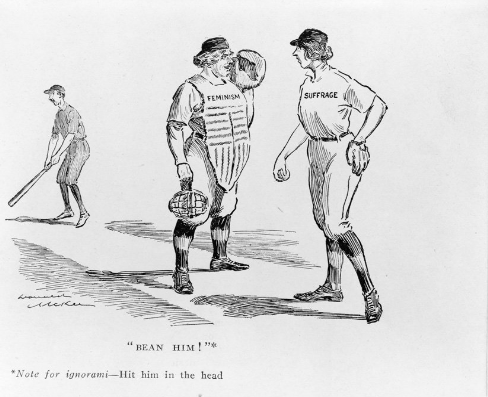

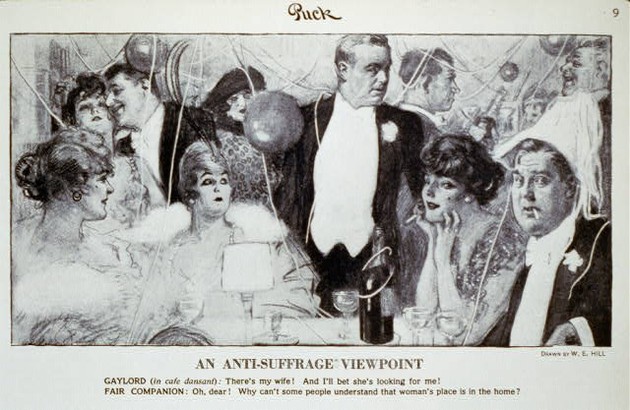

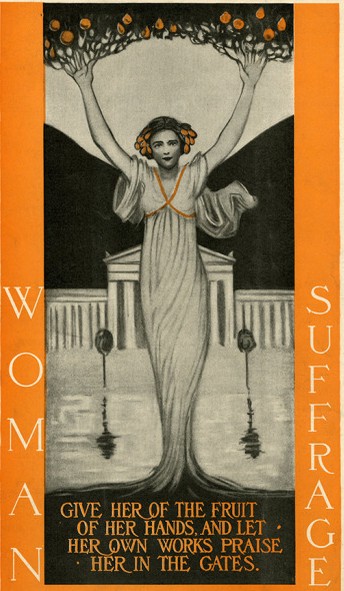

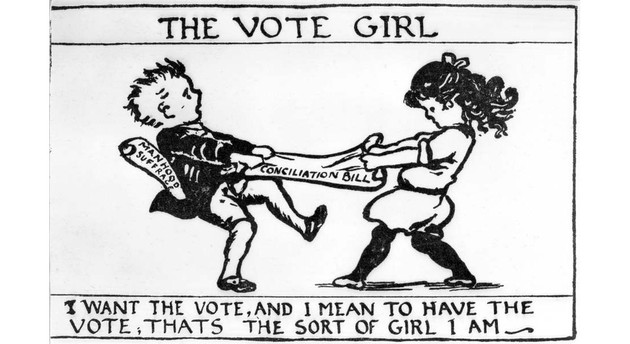

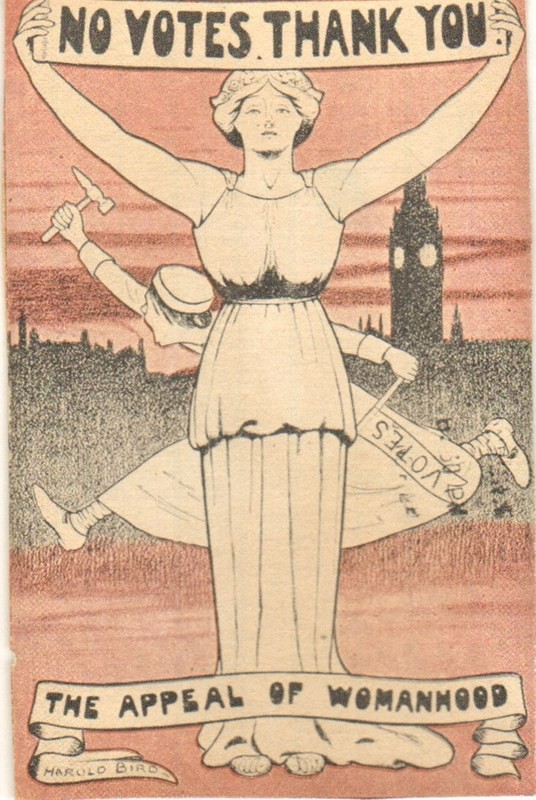

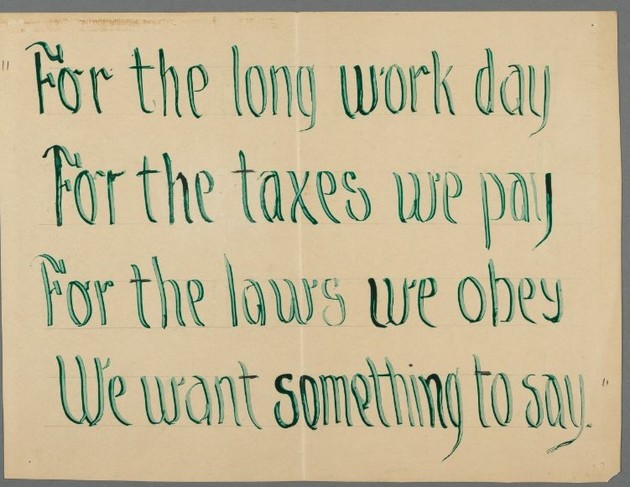

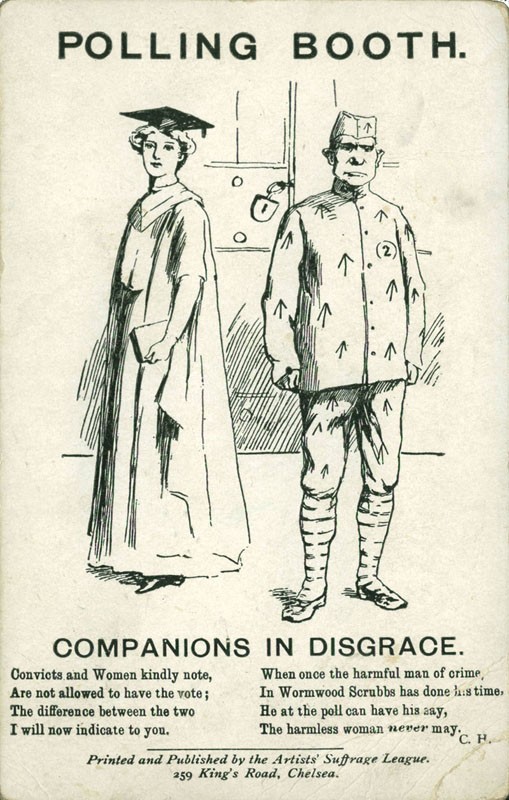

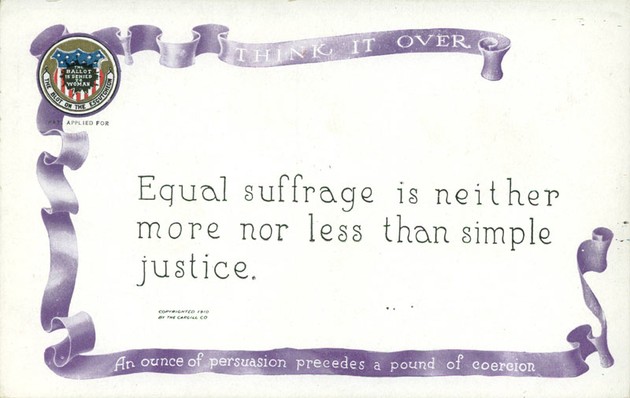

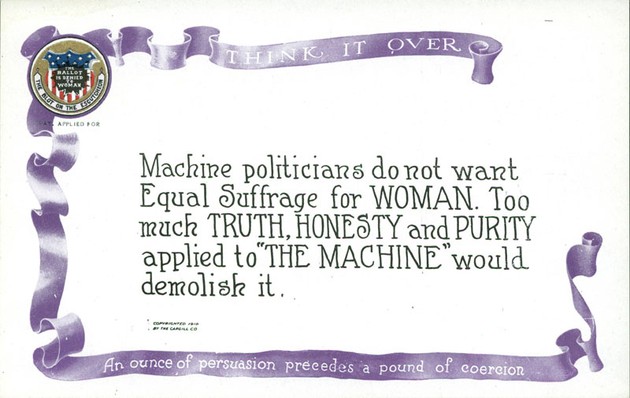

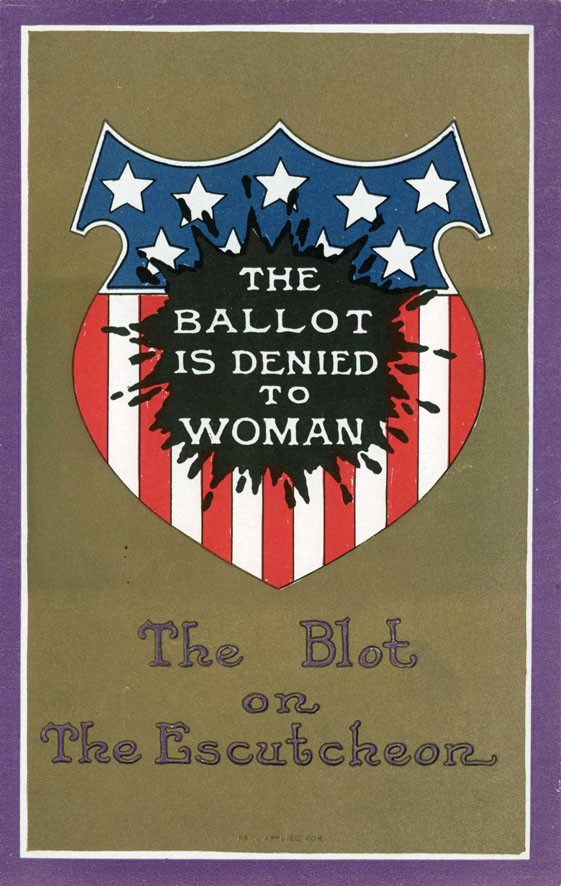

Today’s political dialogue—which often merely consists of opposing sides shouting over one another—echoes another contentious era in American politics, when women fought for the right to vote. Then and now, a mix of political tension and new-fangled publishing technology produced an environment ripe for creating and distributing political imagery. The meme-ification of women’s roles in society—in civic life and at home—has been central to an advocacy tradition that far precedes slogans like, “Life’s a bitch, don’t elect one,” or “A woman’s place is in the White House.”

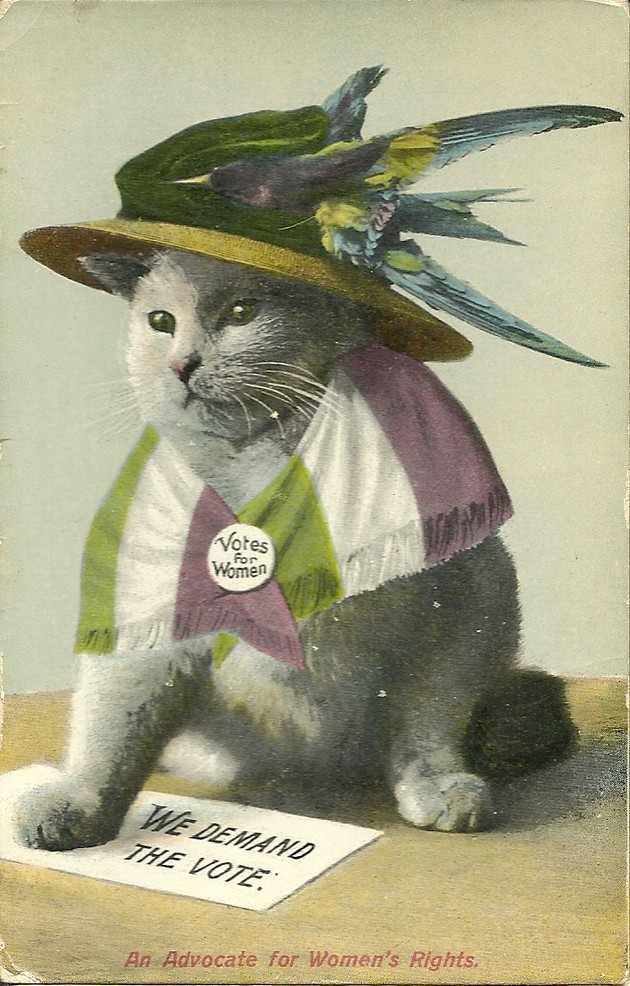

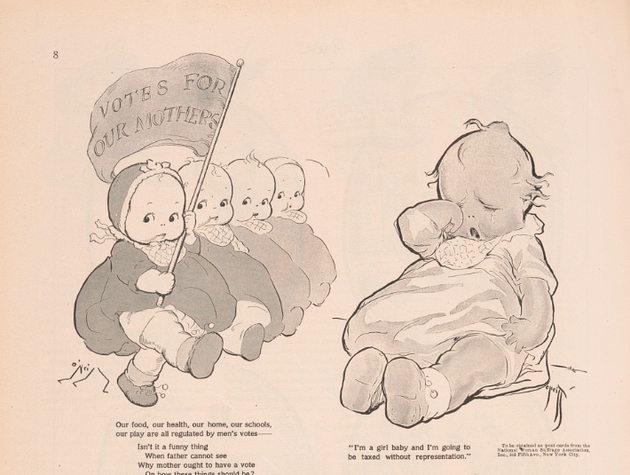

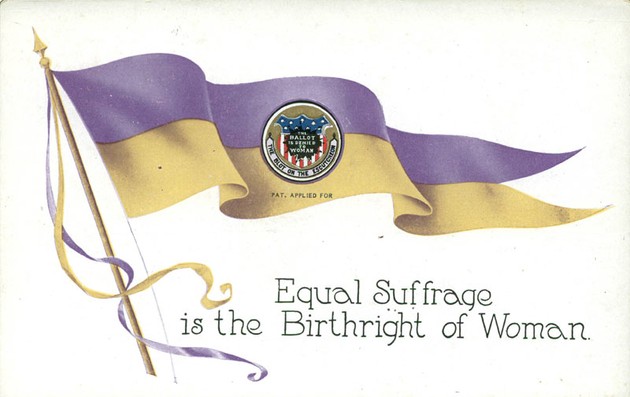

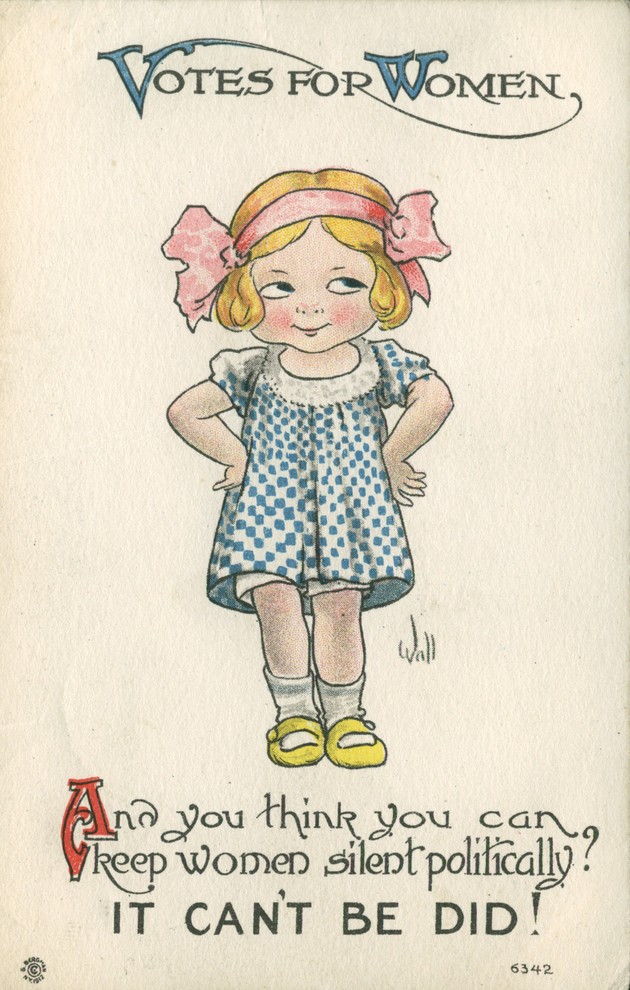

Today’s memes can be found on T-shirts and bumper stickers, yes, but they’re mostly online—published and shared on platforms like Tumblr and Imgur and Twitter. A century ago, political memes were distributed primarily on postcards, via pamphlets, and in newspapers—with suffragettes as a favorite subject of either mockery or admiration, depending on the illustrator’s beliefs.

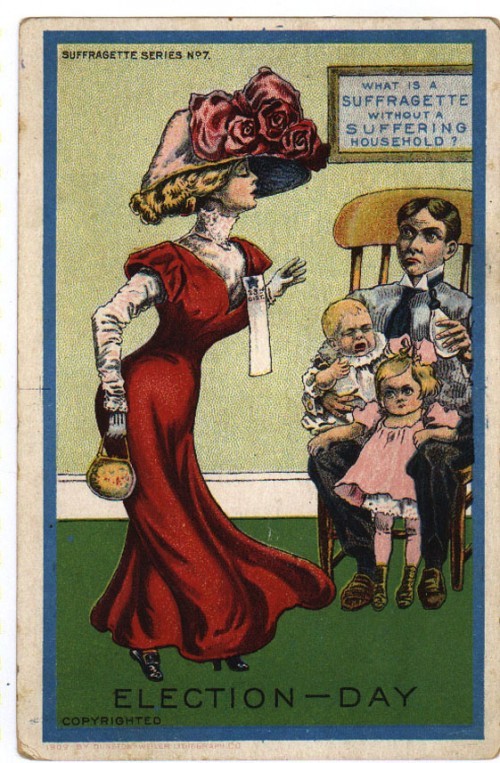

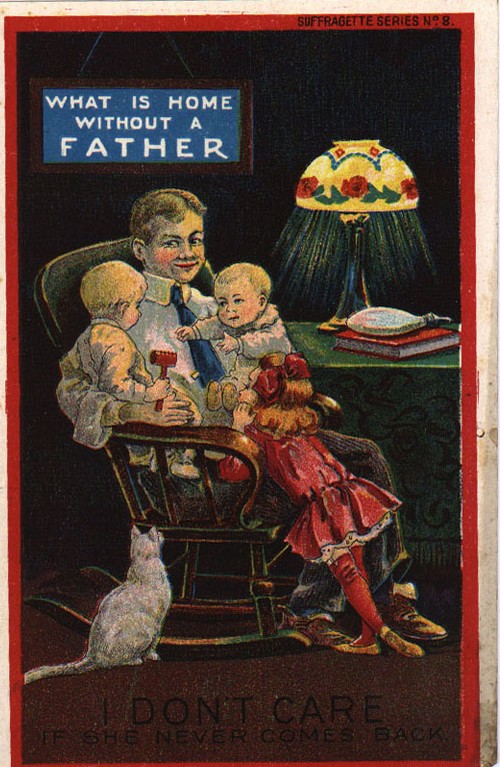

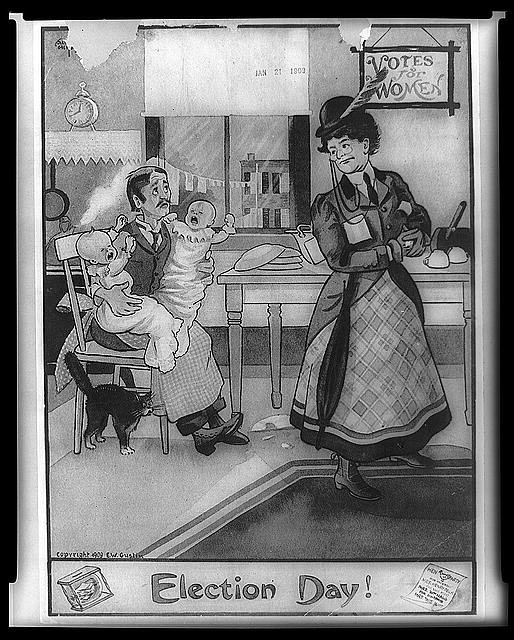

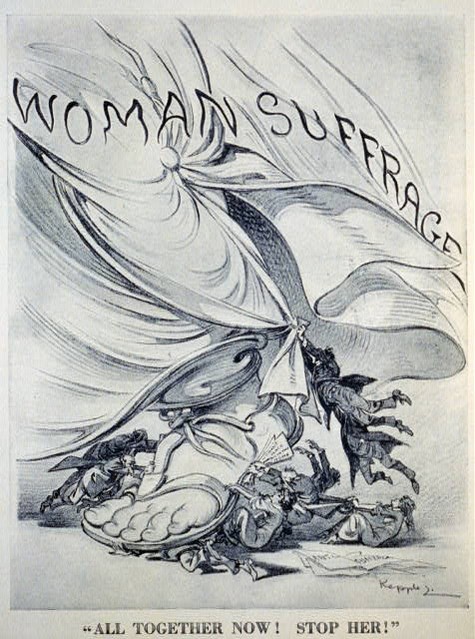

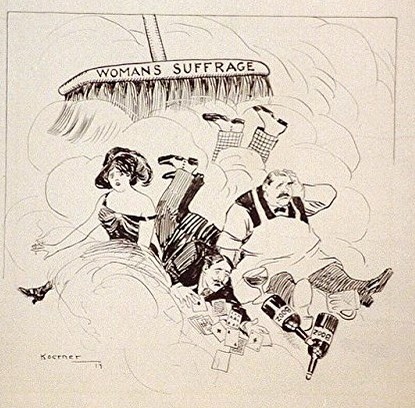

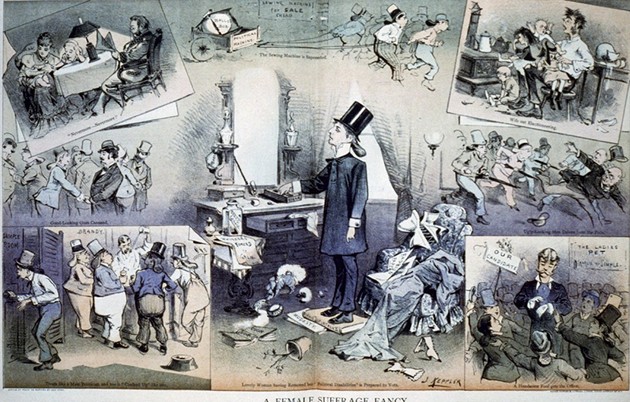

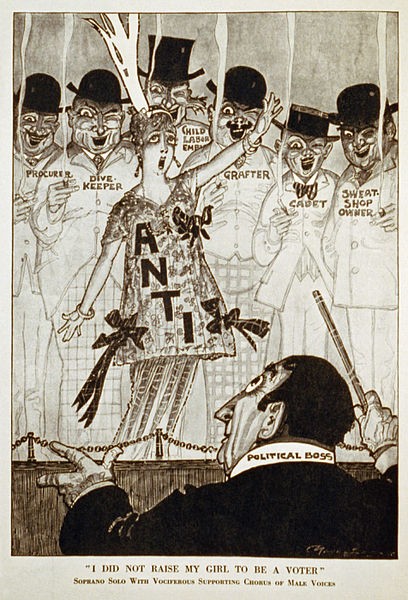

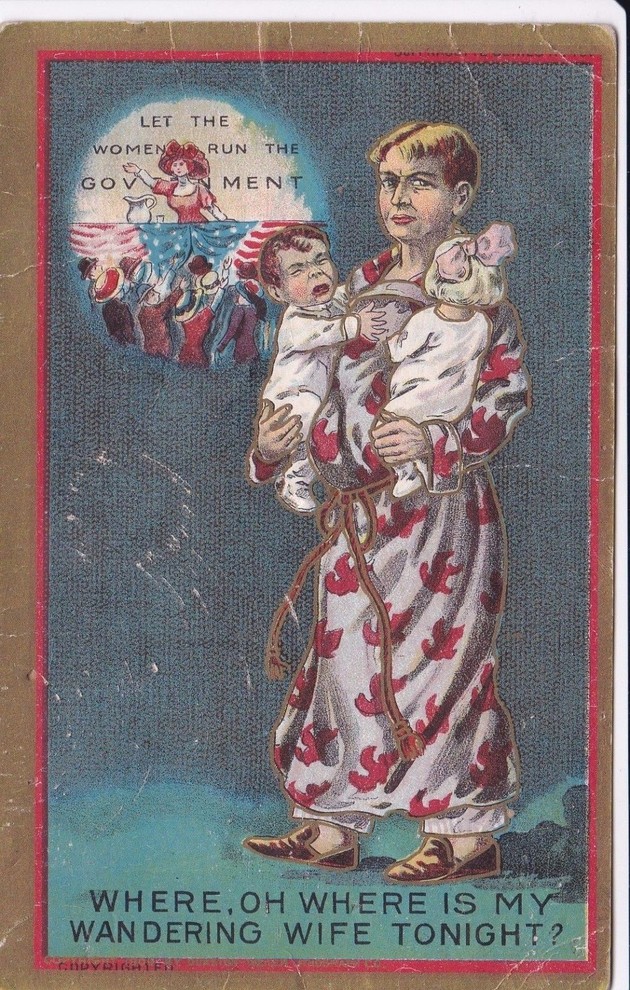

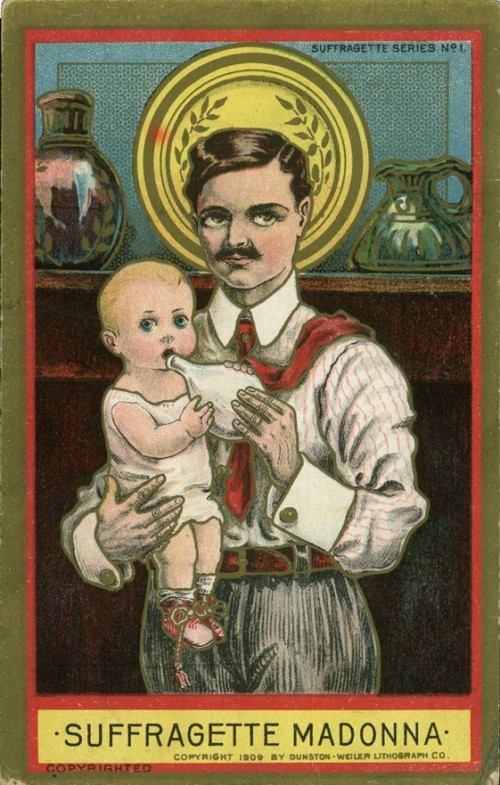

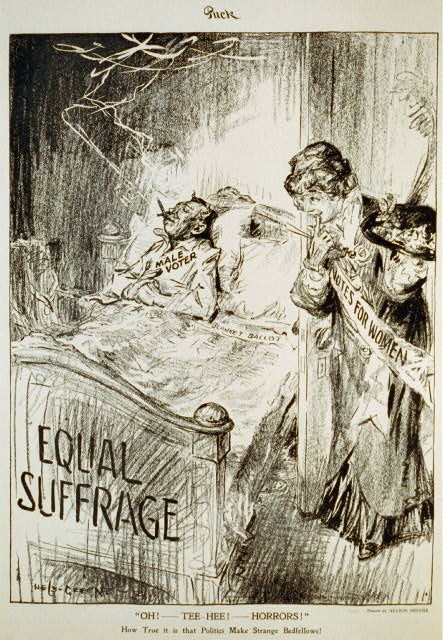

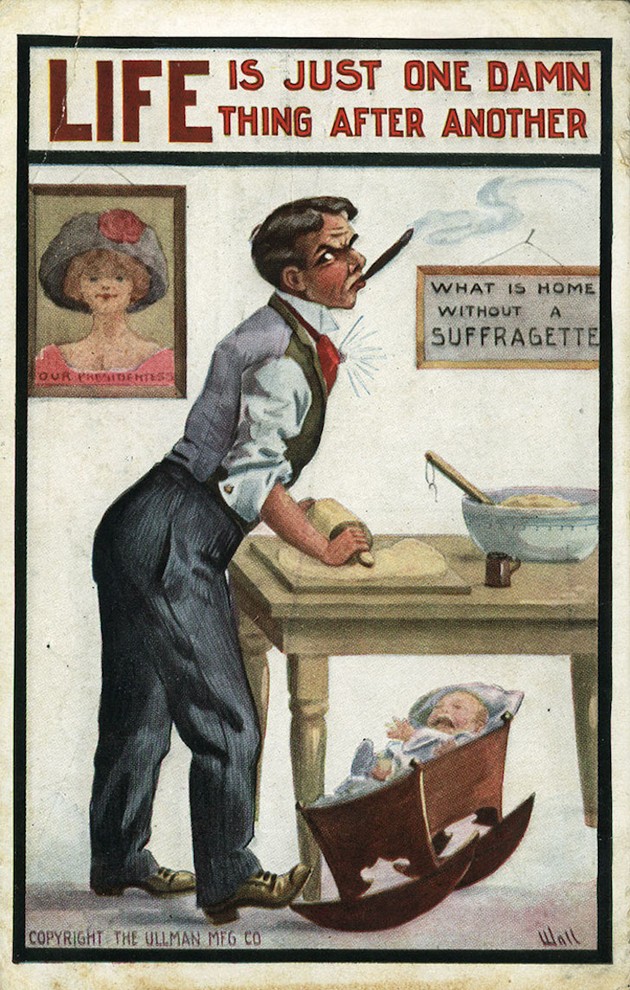

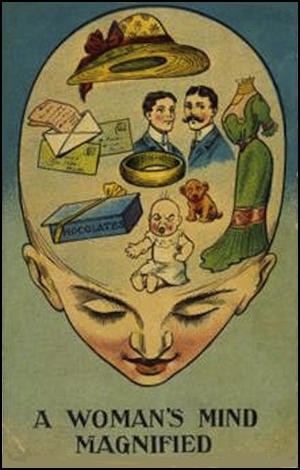

Much of the imagery that circulated in the early 20th century made fun of suffragists, even in illustrations that weren’t explicitly anti-suffrage. Mainstream humor at the time relied heavily on gender-based tropes and stereotypes, and political humor was no exception.“It made no difference that the bulk of this material was not intentionally anti-suffrage,” wrote Lisa Tickner in her 1988 book, The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907-14, “It represented an enormous mass of material, and some very deep-seated prejudice.”

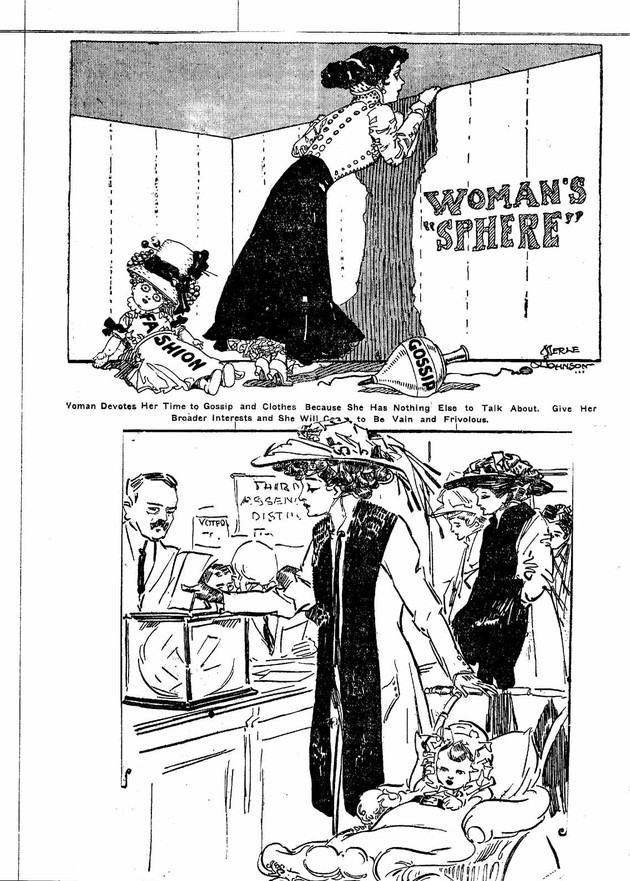

One common theme was the subversion of male and female roles in society—with men often depicted holding crying babies or doing housework, and women portrayed as ultra masculine and detached from home life.

(Catherine H. Palczewski Postcard Archive / University of Northern Iowa)

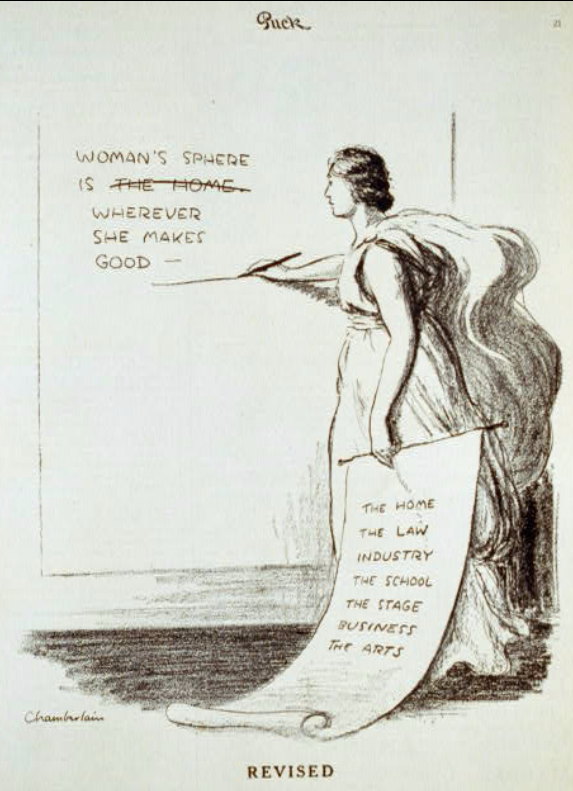

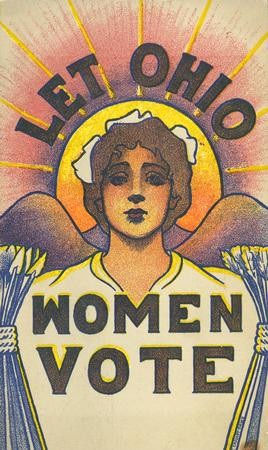

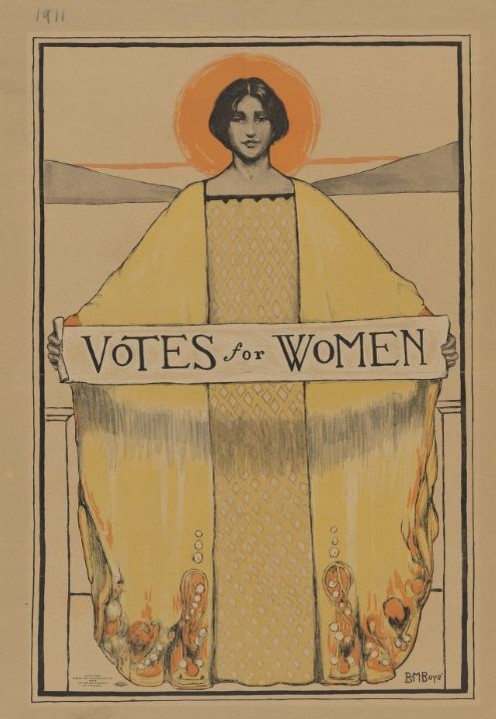

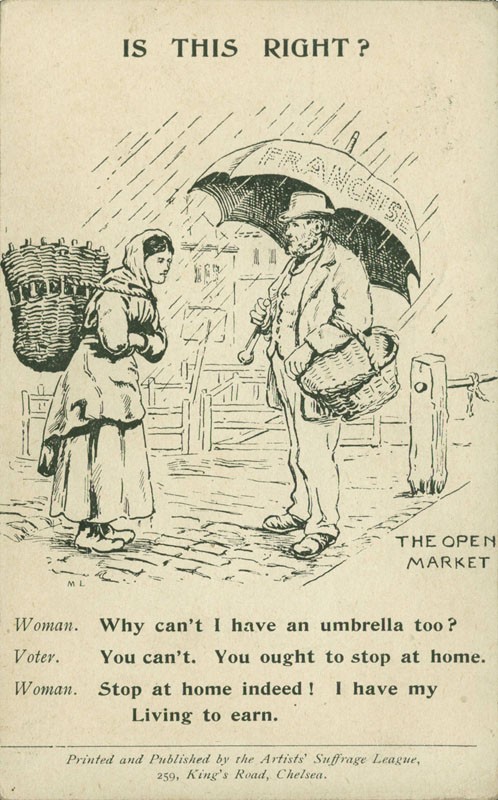

Artists who created works with the intention of promoting suffrage were organized and devoted to the cause, Tickner wrote, “but [their efforts] were very small against the accumulated weight of individual and institutional misogyny.”

Sounds familiar, no?

(Catherine H. Palczewski Postcard Archive / University of Northern Iowa)

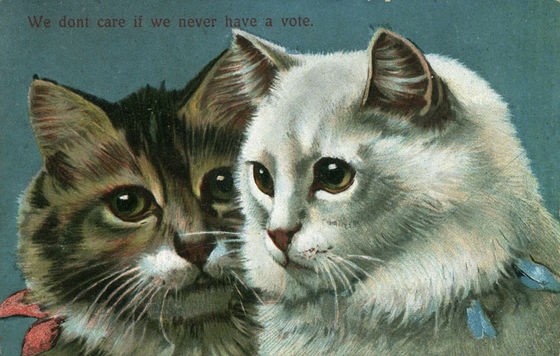

On top of all that, in a sub-genre of suffrage-era propaganda that’s downright internetty, there was even an obsession with cats. (This was likely because of the 1913 Cat-and-Mouse Act, a government strategy to discourage hunger strikes by imprisoned suffragettes in the United Kingdom, according to the historian of social movements Catherine Helen Palczewski.)

As Palczewski points out in an essay accompanying her web collection of suffrage postcards, it was common for people to display albums filled with postcards in their homes in the early 20th century. So it made sense that postcards both supporting and opposing the women’s vote were ubiquitous, especially between 1890 and 1915 in the United States. About 4,500 different suffrage-themed postcards were designed during that time, she wrote.

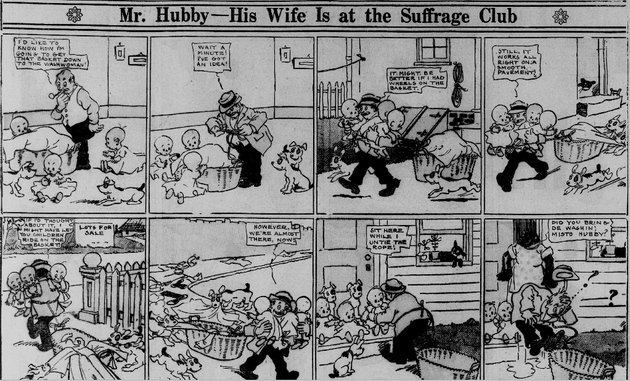

Congress ultimately ratified the 19th Amendment in 1920. But many women, particularly women of color, remained disenfranchised long after that. Early 20th-century suffrage memes were nearly exclusively concerned with white people. In reviewing hundreds of postcards, prints, and illustrations, the only portrayal I saw of a black woman was in a cartoon strip about a white husband struggling to manage housework after his wife had gone off to a suffrage meeting. The woman in the strip is a mammy caricature, only there to help the man with the laundry.

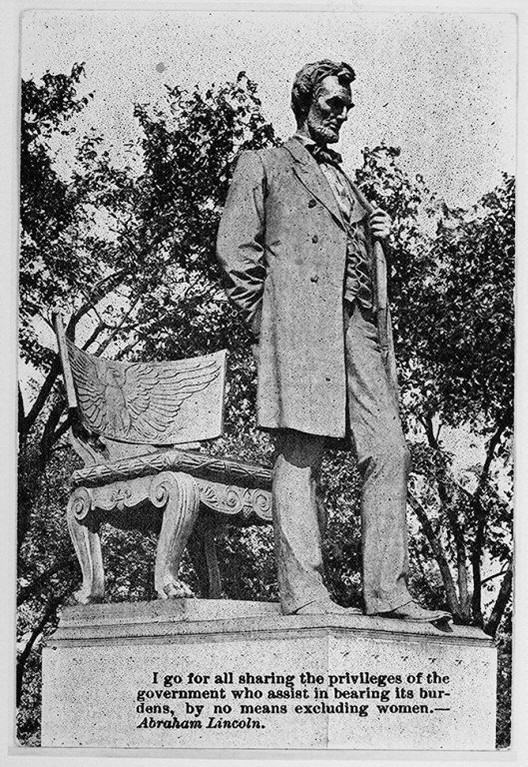

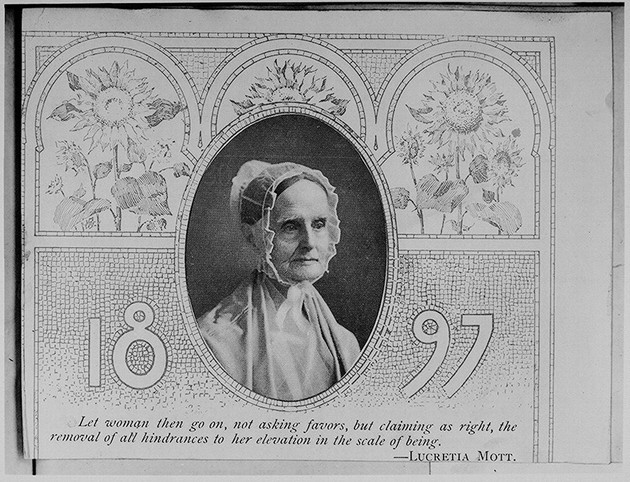

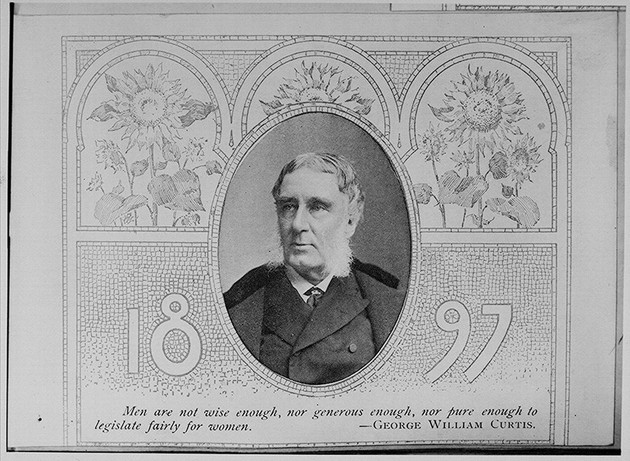

And though the aesthetic of early comics and other memes isn’t exactly contemporary, many of the formats used back in the day—like inspirational quotes overlaying imagery of revered figures—have lived on. You can find this kind of thing all over sites like Pinterest and Reddit today:

In 1941, George Orwell wrote an essay about the endurance of this art form, focusing in particular on the work of Donald McGill, a British illustrator known for his raunchy postcards. His observations remain salient today, and could easily apply to modern collections of political “shitposts.” (The epithet he uses is jarring to read in 2016, but such racist imagery is still being produced.)

They have an utter lowness of mental atmosphere which comes out not only in the nature of the jokes but, even more, in the grotesque, staring, blatant quality of the drawings. The designs, like those of a child, are full of heavy lines and empty spaces, and all the figures in them, every gesture and attitude, are deliberately ugly, the faces grinning and vacuous, the women monstrously parodied, with bottoms like Hottentots. Your second impression, however, is of indefinable familiarity. What do these things remind you of? What are they so like?

Comic postcards, Orwell concluded, were so familiar because they exploited tensions and ideas rooted deeply in Western European consciousness. Finding humor in punching down at women, the depictions of them as grotesque, sexual innuendo at their expense—all this stuff has deep cultural roots. “What you are really looking at,” he wrote, “is something as traditional as Greek tragedy.” Which, of course, brings us back to the 2016 election.

Outspoken and civically engaged women are still a target for humorists and activists, routinely cast as either larger-than-life saviors or power-thirsty demons destroying modern society. “To her critics, the modern woman was a symptom of the social decline she helped to precipitate,” Tickner wrote of the way suffragettes were perceived during the presidential campaign of 1908, “To her champions, she was not unwomanly, but womanly in a new and developing way.”

The only consensus, it seems, is that a woman’s political ambitions cannot be ignored.

(Library of Congress)

(The Suffrage Postcard Project)

(Library of Congress)

(Catherine H. Palczewski Postcard Archive / University of Northern Iowa)