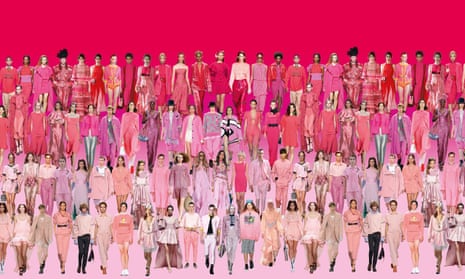

Gravadlax. Rose quartz. Calamine. Taffy. Watermelon. Elastoplast. No, it’s not the world’s most esoteric shopping list, but the colours you need in your wardrobe this season. The names are bewildering, but the message is clear: this season is about pink. But not as you know it.

When this spring’s collections hit the catwalks last September, New York’s post-punk, rave-referencing Marc Jacobs stirred controversy, with the flamingo- and fuchsia-coloured dreadlocks worn by Kendall Jenner and the Hadid sisters, sparking a row about cultural appropriation. Next came London, where milliner Stephen Jones dreamed up outsize pirate hats to match Ryan Lo’s Venetian harlequin-printed jumpsuits in fuchsia satin.

Then it was straight from Milan airport to the Gucci catwalk show, where we found ourselves in a tripped-out, tricked-out, all-pink venue. A lush carpet in magenta stripes was dotted with candyfloss velvet banquettes against pink mirror-tiled walls. Through a dry-ice fug that intensified the womb-like intensity of the venue, the first model stepped out from behind glittering curtains in a pink blouse, peony-bright lapels laid proud and wide over a grey-and-pink windowpane check blazer and topped with a rose-trimmed pink turban and enormous sunset-tinted sunglasses.

But it was Paris where the trend came of age, at the end of the show season carousel, with a week in which the pink dress was as ubiquitous on the catwalk as the navy blazer was a few years ago. Ubiquitous, that is, but never predictable. At Céline the pink dress was lushly draped and caped across the shoulder, worn with different colour shoes in the manner popularised by Mario Balotelli on the football pitch. At Balenciaga, a high-necked fuchsia dress was anything but prim when styled over thigh-high latex stilettos in ultraviolet. In 2017, pink has gone rogue.

Pink is the most gender-loaded of colours, interlaced with femininity in everything from toy-store branding to the pink pussy hats of January’s Women’s March in Washington. Which you would have thought makes right now a surprising season for the colour to enjoy a revival, because the fashion industry’s pre-eminent obsession is gender fluidity. Raf Simons at Calvin Klein, Alessandro Michele at Gucci and Christopher Bailey at Burberry are three of the most influential fashion leaders of the moment. The men have contrasting aesthetics, personal styles and attitudes to brand building, so it is striking that they are all in agreement on one message: all three brands have recently combined their menswear and womenswear collections into one catwalk show. Meanwhile, high-street favourite Zara’s ungendered collection, launched last year, is proof that gender fluidity is happening IRL, not just as some arthouse catwalk fantasy.

An odd moment, then, for fashion to put on its rose-tinted glasses. But look at it another way: gender fluidity is about challenging what gender means, and nothing brings gender into the fashion conversation faster than the colour pink. And the new pink is seldom straightforwardly pretty, but rather used to challenge the assumptions we make about what femininity should look like. Even, perhaps, as a lens through which to consider the ways in which wardrobe conventions help prop up gender roles. And if this sounds like it’s getting a little overwrought – hey, welcome to modern feminism and the politics of fashion.

Modern pink is complicated. The Pinkstinks campaign takes a straightforwardly oppositional stance, targeting the role of pink-saturated marketing in railroading young girls into painfully narrow stereotypes. But a new generation of culturally aware young women are taking a different approach to the same problem, subverting or reclaiming pink.

Subversion, for instance, in the case of feminist poet and photographer Lora Mathis, who created a striking and much-pinned image of a place setting on a lush pink tablecloth with bread knife, carving knife and penknife in place of fork, knife and spoon, surrounding a plate of pearls on which the words “Radical softness as a weapon” are spelled out in childlike alphabet beads. In place of salt and pepper shakers, the table is ornamented by crude pink plastic clip-on earrings of the type that are sold with Disney princess costumes.

And then there are the reclaimers: the case of the young millennials who have made “Tumblr pink” – an urbane dusty nude – a favourite colour for twentysomething women.

Did I say women? My bad. To equate pink with women’s fashion no longer makes sense. The colour is as likely to be seen in a menswear collection as it is in the little girls’ party dress department. Pink, once spotted on loafer-clad men on Sloane Street, has emerged as a staple of men’s fashion over the past decade, its popularity a blossoming litmus test of male confidence in the fashion arena. As the movement towards bringing gender together on the catwalk with joint fashion shows has grown, so has the profile of pink. A shade that once embodied gender hang-ups has become the club colour proudly worn by a fashion generation for whom post-gender is reality, not science fiction.

It should come as no surprise that the germ of today’s pink trend began with that most talented of modern visual messengers, Kim Kardashian. In the autumn of 2013, after the birth of her daughter North West, she embarked on a striking makeover that shifted her look from the vaudeville pomp of her reality-star aesthetic to a more haute, front-row-friendly look. The palette of her new wardrobe, every item of which was extensively documented on social media in the time it took Kim to emerge from the revolving door of her hotel, centred around pale blush, soft camel and rose pink. An ankle-length Céline coat in soft ballet-slipper pink, which had hitherto been admired only within insider fashion circles, was catapulted on to the world stage.

In September 2013, the same month that Kim was slaying Paris in her pink coat, Cara Delevingne starred in a pink-themed shoot in British Vogue that saw her carrying two puppies dyed a fetching shade of sugar pink, and Marks & Spencer’s £85 pink duster coat became a high-street sensation. Fast-forward six months and the first look of Chanel’s blockbusting autumn/winter 2014 show, which saw the interior of the Grand Palais in Paris reinvented as a supermarket, was Cara Delevingne, the girl of the hour, in a ripped, ab-baring pink tracksuit. By early 2015, saccharine pale pinks were all over fashion week, from Topshop Unique’s crushed velvet trouser suit to Prada’s sugary double-breasted blazers, slightly shrunken so that the models took on awkward, Alice In Wonderland proportions. Dismiss pink at your peril, for this is no flash in the pan.

Pink has always been complicated. For a start, it became associated with femininity only halfway through the 20th century, before which it was a colour worn by flamboyant men. In 1837, the rowers of Westminster school and Eton college raced for the right to wear pink; Westminster’s rowers wear the colour to this day. Historically, women in art are more likely to be depicted in blue, the colour traditionally worn by the Virgin Mary. Renoir’s girls wear blue; so do Degas’s ballerinas. It was only in the 50s that pink became the cipher for femininity in that decade’s very binary notion of gender. Think of Marilyn Monroe’s wardrobe in 1953’s How To Marry A Millionaire, and Jayne Mansfield’s Sunset Boulevard mansion, the Pink Palace, with its heart-shaped pool and strawberry-tiled bathroom.

That was 70 years ago. The world has moved on, and pink with it. This spring, the meaning of pink is bold, not baby talk. The question is, are you woman – or man – enough to wear it?

This article appears in the spring/summer 2017 edition of The Fashion, the Guardian and the Observer’s biannual fashion supplement

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion