Activists in Hong Kong and China struggle to keep memories of 1989 Tiananmen crackdown alive after nearly three decades of silence from Beijing

As China continues to snuff out any remembrance of the violence on June 4, 1989, campaigners face an uphill battle to convince the next generation that their struggle still matters

Making his way through a sea of candlelight at the annual Victoria Park vigil commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, Beihai, a university undergraduate from the mainland, found himself fighting back tears.

Alongside tens of thousands of participants, the 21 year old sang his heart out to emotional songs such as With a dream that won’t die, let us remember.

“Cantonese is not my first language, so I felt an obvious cultural difference.

“But seeing their support for pro-democracy movements in China made me feel attached to them.”

It was June 4, 2007, and Beihai was attending the gathering for the first time. “It was a feeling of excitement about approaching the truth.”

But for many mainlanders, the truth could hardly be further away.

In 1989, on the night of June 3 and morning of June 4, the government in Beijing deployed military units to disperse demonstrators who had been camped on Tiananmen Square for weeks. The operation resulted in hundreds, possibly more than a thousand, losing their lives – the death toll has never been disclosed.

The incident has been excised from public memory across China. The communist regime rarely mentions it and when it does refers to it blandly as “political turbulence between the spring and summer of 1989”.

Save for a small vigil in Macau, Hong Kong has been the only place in the country to organise major events to mark the crackdown. Campaigners in the city have exercised their freedoms under the “one country, two systems” formula by which Hong Kong is governed to keep their activities at arm’s length from Beijing.

Twenty years on from the city’s return to Chinese rule, Hong Kong still allows its residents to openly remember the pro-democracy movement, and media reports every June 4 in the former British colony stand alone among silence from counterparts across the border.

Beihai, now 31, has been back each year since 2007 for all but one of the vigils. For him, the occasion is as much a focal point for aspirations for greater freedoms on the mainland as it is to remember what some call the darkest moment in modern Chinese history.

“Censorship is very heavy on the mainland. It’s a luxury to openly express myself on such issues,” he said.

For Beijing and government loyalists in Hong Kong however, scenes of thousands dressed in black, holding candles and shouting “end one-party rule” make for unpalatable viewing.

Chief executive-elect Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, who called June 4 “saddening” when an election candidate and said “history will have its judgment”, declined to comment for this report.

Nearly two decades ago, then Chinese premier Zhu Rongji, when asked about calls from Hongkongers to vindicate the 1989 crackdown, said the party’s verdict on it would not change.

But hinting at tolerance of the city’s affairs, Zhu suggested Hong Kong enjoyed the freedom to demonstrate as long as Hong Kong laws were observed.

“The Hong Kong people are free to protest or march if I go to Hong Kong,” Zhu said, answering a question in 1998 about his thoughts if the city pressed him on the issue of June 4 during his visit. “But I think any events should follow the Basic Law and laws in Hong Kong.”

Still, activists wanting to remember the crackdown with a museum have encountered obstacles.

A space inside a commercial building in Tsim Sha Tsui was used initially until the owners objected. This year it moved to a temporary site in a cultural centre in Shek Kip Mei. The Hong Kong government has offered no help at all.

But an even bigger threat confronting efforts to commemorate June 4 comes not from Beijing, but Hong Kong’s youth.

For many young people, what happens on the mainland matters less and less as Hong Kong forges its own identity after two decades free from colonial rule. Many care little about “building a democratic China” – the vigil’s expressed aim.

Justin Au Tze-ho, president of the student union at Chinese University, which this year for the first time will not take part in the vigil or organise its own commemorative events, said: “When students were discussing whether to do something, we asked ourselves, what is the meaning behind doing something for June 4?

“We do not agree with the call to build a democratic China.”

In the first decade and a half after the handover, the philosophy of democracy supporters in Hong Kong bore near-complete resemblance to those of students at Tiananmen Square; both groups wanted the Communist Party leaders to listen and act on the demands for democracy from the next generation.

Many Hong Kong youngsters, rather than clamouring for democratic change on the mainland, have instead begun to embrace the idea of a rejection of Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong, happy to disassociate themselves from mainland affairs. Many have little or no memory of news reports showing the midnight spectacle of gunfire and tanks rolling through Beijing on June 4, 1989.

Observers mourn this rejection of June 4 ceremonies, in contrast to other historic tragedies such as the Holocaust or the rape of Nanking, for which such a snub would be unthinkable.

“Remembering June 4 is a core element of what defines Hong Kong,” said Albert Ho Chun-yan, the alliance’s chairman and a former Democratic Party lawmaker. “It is through our consistent call for vindication over a needless bloody crackdown that Hongkongers write our own history.”

The vigil also serves as the only channel for justice for those who lost loved ones.

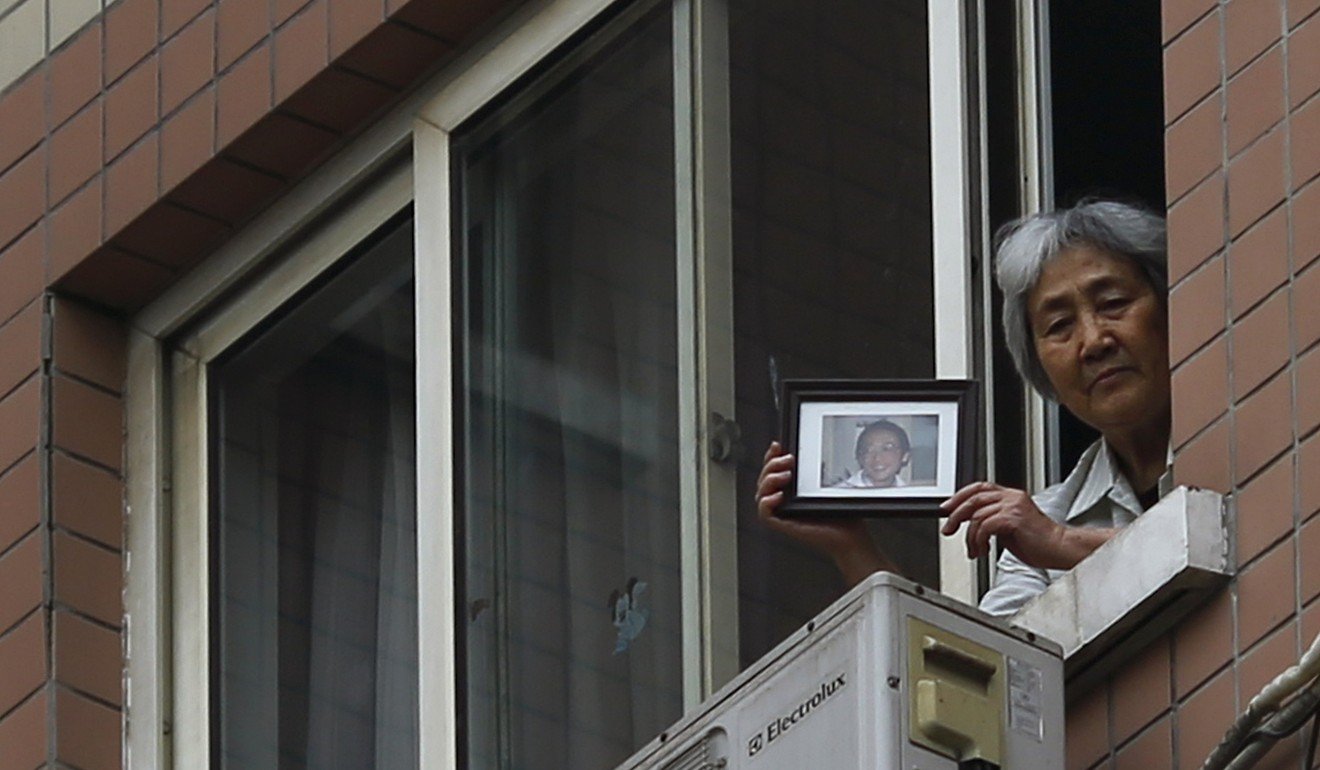

“Every year, the gathering serves as emotional support for relatives of the victims. It’s enlightening for the public and a prick of pain for the central government,” said Zhang Xianling, whose 19-year-old son was shot dead during the crackdown.

Zhang, a leading member of the Tiananmen Mothers, a group that comprises parents, spouses and friends of the victims from 1989, said the support from Hong Kong had been more than spiritual.

“Donations from the vigil have helped some of our fellow relatives of the victims send their children to college or cover medical fees for the elderly,” she said. “The support from Hong Kong has been very sincere and helpful.”

Remembering June 4 is a core element of what defines Hong Kong

The Tiananmen Mothers aim to press the government in Beijing to change its attitude towards the episode. Zhang, who still lives in the capital, said the central government had barely answered their repeated calls to vindicate the 1989 protesters, who are still officially deemed “rioters”. But the 79 year old remains hopeful.

“I don’t think the effect will be that immediate,” she said.

Zhang’s appreciation for Hong Kong’s support is echoed by Ma Shaofang, one of the 21 student leaders on Beijing’s wanted list amid a massive manhunt after the crackdown. Ma, who lives in Shenzhen, said a rise in political awareness on the mainland could partly be attributed to Hong Kong.

“Though the pro-democracy movement on the mainland was never big enough to let us feel a wave of democratic change, the people have grown more aware of their rights and proactive in pursuing those rights,” he said.

Today, Ma remains under close watch by the authorities and has never managed to attend the vigil at Victoria Park.

Still, for him, “the encouragement from Hong Kong has played an important role. Hong Kong’s fight for freedom of speech and universal suffrage has profoundly influenced a rise in activism on the mainland.

“I think mainland people owe Hongkongers an apology. We did too little, if anything, when Hong Kong was oppressed by Beijing,” Ma said. “Hongkongers have always offered their help for us but we seldom do anything in return.”

During the 2014 Occupy protests in Hong Kong, when demonstrators staged a 79-day sit-in to demand universal suffrage, a handful of rights activists on the mainland staged protests in solidarity.

But most mainlanders were unaware of the significance of the action or were indifferent, if not resentful, towards what state media labelled a “pro-independence” rally.

The Hong Kong Tiananmen vigil is also a moment of collective memory that “gains its potency from the Communist Party’s attempts to quash acts of remembrance of June 4 elsewhere on Chinese soil”, said Louisa Lim, the US-based author of The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited.

“Hong Kong’s vigil plays a crucial role in keeping the memory of June 4 alive.”

A vigil will also be held in Taipei, as in previous years, where similar debates between anti- and pro-China camps run even deeper.

But comparing the two, “the Hong Kong vigil means much more than the Taiwan one, because Hong Kong is officially part of China and it’s a key channel for voicing discontent to Beijing,” said Wang Dan, a key Tiananmen student leader.

After a seven-year stay as an academic in Taiwan, Wang will be returning to the United States this month to set up a think tank to “advocate human rights and democracy” on the mainland.

For Bao Tong, the ousted top aide of Zhao Ziyang, the top Chinese official purged by paramount leader Deng Xiaoping following his opposition to the military crackdown, June 4 has become a date every year for which he is taken away from Beijing to spend time “holidaying” elsewhere.

Eleven years after his release from jail, Bao’s life has barely changed, with his every move under close watch. He is given limited freedom to travel within the capital, and authorities keep a log of every guest going into and out of his house.

Bao never fails to catch video clips and photos of the Victoria Park vigil his friends send him every year by phone. But at 85, he sees no sign of democratic reform coming on the mainland, more than a century after the fall of dynastic rule in China at the hands of activists who dreamed of a democratic nation.

“I’d love to see it [democracy for China] in my lifetime, but even if I can’t, I still remain hopeful.

“Not everyone can witness the moment,” Bao said. “But I guess what matters more is, while you are still alive, fight for it and make your own contribution.”

Organisers expect as many as 150,000 at 2017 vigil

The organisers of the June 4 vigil expect 100,000 to 150,000 people to join the rally in Victoria Park this year, according to police.

The event, put together by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, will start at 8pm on Sunday at the park in Causeway Bay. The official theme this year is “Vindicate June 4, End Dictatorial Rule”.

Three groups other than the alliance will hold rallies on the outskirts of the park, near Hang Lung Centre and Lau Sin Street, said Tse Kwok-wai, the police force’s senior superintendent (operations) on Hong Kong Island.

Tse refused to say how many officers would be deployed to police the event. But Tsoi Yiu-cheong, vice-president of the alliance, said 200 to 300 volunteers and staff would help maintain order.

A spokesman for Demosisto, a youth-led political party, said its members would march with the group Student Fight For Democracy and the League of Social Democrats to the central government’s liaison office in Western district after the vigil.

However, Tse said the police had not received any application for such a demonstration.

The number taking part in the vigil fell to 125,000 last year after hitting a peak of 180,000 in 2014, as some university student organisations quit the event and new political groups held their own rallies on June 4.

Last Sunday, an annual memorial march organised by the alliance drew just 1,000 people, a nine-year low. But Tsoi said the numbers in recent years were neither small nor the worst in the vigil’s history since it was first held in 1990.