Are You Sure You Want Single Payer?

“Medicare for all” is a popular idea, but for Americans, transitioning to such a system would be difficult, to say the least.

French women supposedly don’t get fat, and in the minds of many Americans, they also don’t get stuck with très gros medical bills. There’s long been a dream among some American progressives to truly live as the “Europeans1” do and have single-payer health care.

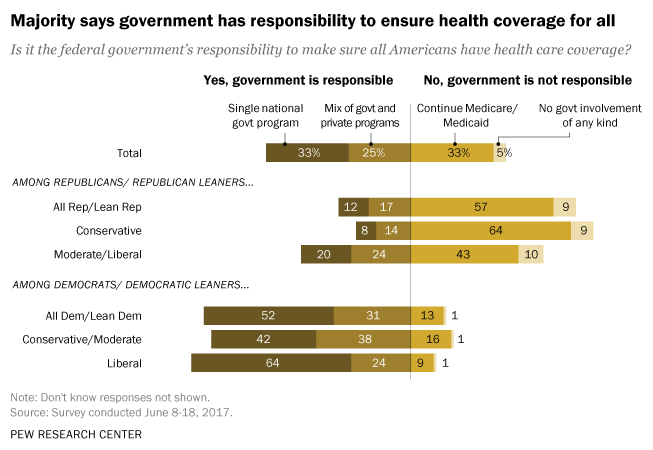

Republicans’ failure—so far—to repeal and replace Obamacare has breathed new life into the single-payer dream. In June, the majority of Americans told Pew that the government has the responsibility to ensure health coverage for everyone, and 33 percent say this should take the form of a single government program. The majority of Democrats, in that poll, supported single payer. A June poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation even found that a slim majority of all Americans favor single payer.

Liberal politicians are hearing them loud and clear. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders reportedly plans to introduce a single-payer bill once Congress comes back from recess—even though no Senate Democrats voted for a single-payer amendment last month. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren has also said “the next step is single payer” when it comes to the Democrats’ health-care ambitions.

But should it be? It’s true that the current American health-care system suffers from serious problems. It’s too expensive, millions are still uninsured, and even insured people sometimes can’t afford to go to the doctor.

Single payer might be one way to fix that. But it could also bring with it some downsides—especially in the early years—that Americans who support the idea might not be fully aware of. And they are potentially big downsides.

First, it’s important to define what we mean by “single payer.” It could mean total socialized medicine, in that medical care is financed by—and doctors work for—the federal government. But there are also shades of gray, like a “Medicaid for all” system, where a single, national insurance program is available to all Americans, but care is rationed somewhat—not every drug and device is covered, and you have to jump through hoops to get experimental or pricier treatments. Or it could be “Medicare for all,” in which there’s still a single, national plan, but it’s more like an all-you-can-eat buffet. Like Medicare, this type of single-payer system would strain the federal budget, but it wouldn’t restrict the treatments people can get. Because it’s the term most often used in single-payer discussions, I’ll use that here.

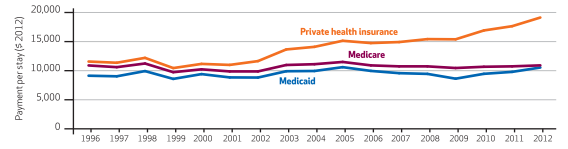

The biggest problem with Medicare for all, according to Bob Laszewski, an insurance-industry analyst, is that Medicare pays doctors and hospitals substantially less than employer-based plans do.

Average Standardized Payment Rates Per Inpatient Hospital Stay, By Primary Payer, 1996-2012

“Now, call a hospital administrator and tell him that his reimbursement for all the employer-based insurance he gets now is going to be cut by 50 percent, and ask him what’s going to happen,” he said. “I think you can imagine—he’d go broke.” (As it happens, the American Hospital Association did not return a request for comment.)

The reason other countries have functional single-payer systems and we don’t, he says, is that they created them decades ago. Strict government controls have kept their health-care costs low since then, while we’ve allowed generous private insurance plans to drive up our health-care costs. The United Kingdom can insure everyone for relatively cheap because British providers just don’t charge as much for drugs and procedures.

Laszewski compares trying to rein in health-care costs by dramatically cutting payment rates to seeing a truck going 75 miles an hour suddenly slam on the brakes. The first 10 to 20 years after single payer, he predicts, “would be ugly as hell.” Hospitals would shut down, and waits for major procedures would extend from a few weeks to several months.

Craig Garthwaite, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, says “we would see a degradation in the customer-service side of health care.” People might have to wait longer to see a specialist, for example. He describes the luxurious-sounding hospital where his kids were born, a beautiful place with art in the lobby and private rooms. “That’s not what a single-payer hospital is going to look like,” he said. “But I think my kid could have been just as healthily born without wood paneling, probably.”

He cautions people to think about both the costs and benefits of single payer; it’s not a panacea. “There aren’t going to be free $100 bills on the sidewalk if we move to single payer,” he said.

He also predicts that, if single payer did bring drug costs down, there might be less venture-capital money chasing drug development, which might mean fewer blockbuster cures down the line. And yes, he added, “you would lose some hospitals for sure.”

Amitabh Chandra, the director of health-policy research at Harvard University, doesn’t think it would be so bad if hospitals shut down—as long as they’re little-used, underperforming hospitals. Things like telemedicine or ambulatory surgical centers might replace hospital stays, he suspects. And longer waits might not, from an economist’s perspective, be the worst thing, either. That would be a way of rationing care, and we’re going to desperately need some sort of rationing. Otherwise “Medicare for all” would be very expensive and would probably necessitate a large tax increase. (A few years ago, Vermont’s plan for single payer fell apart because it was too costly.)

If the United States decided not to go that route, Chandra says, we would be looking at something more like “Medicaid for all.” Medicaid, the health-insurance program for the poor, is a much leaner program than Medicare. Not all doctors take it, and it limits the drugs and treatments its beneficiaries can get. This could work, in Chandra’s view, but many Americans would find it stingy compared to their employers’ ultra-luxe PPO plans. “Americans would say, ‘I like my super-generous, employer-provided insurance. Why did you take it away from me?’” he said.

Indeed, that’s the real hurdle to setting up single payer, says Tim Jost, emeritus professor at the Washington and Lee University School of Law. Between “80 to 85 percent of Americans are already covered by health insurance, and most of them are happy with what they’ve got.” It’s true that single payer would help extend coverage to those who are currently uninsured. But policy makers could already do that by simply expanding Medicaid or providing larger subsidies to low-income Americans.

Under single payer, employers would stop covering part of their employees’ insurance premiums, as they do now, and people would likely see their taxes rise. “As people started to see it, they would get scared,” Jost said. And that’s before you factor in how negatively Republican groups would likely paint single payer in TV ads and Congressional hearings. (Remember death panels?) It would just be a very hard sell to the American public.

“As someone who is very supportive of the Democratic party,” Jost said, “I hope the Democrats don’t decide to jump off the cliff of embracing single payer.”

- Common misconception: Not all European countries have single payer. ↩