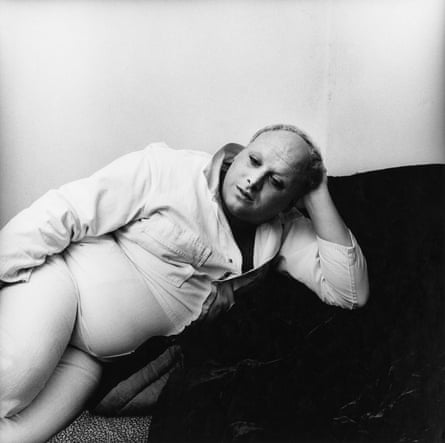

The photograph on the cover of Antony and the Johnsons’ breakthrough album I am a Bird Now is Candy Darling on Her Deathbead, 1973. The photograph Hanya Yanagihara chose for the cover of her Booker-shortlisted second novel A Little Life is Orgasmic Man, 1969. Both pictures are by Peter Hujar, the photographer who lived and worked in poverty in New York until he died in 1987, aged 53, of Aids-related pneumonia. Hujar may have been a prominent figure for two decades in the small bohemian art world downtown, but his name is hardly writ large in conventional histories of photography. So why do 21st-century artists hold his work in such high regard?

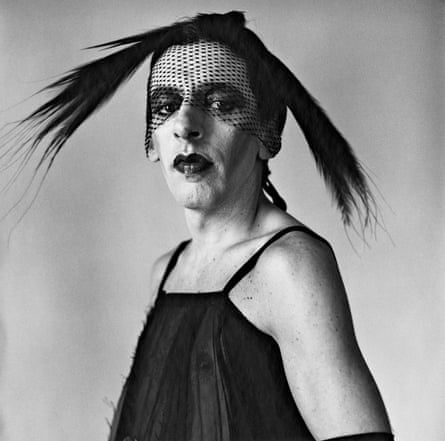

“In many ways Peter Hujar defined downtown for me,” writes veteran photography critic and close friend Vince Aletti in his introduction to Lost Downtown, a new book of Hujar’s portraits in which Aletti appears. “He went places I never dared to, and hung out with people I’d only read about.” Some of these people – such as drag queen and actor Divine, artist David Wojnarowicz, writers Susan Sontag and William Burroughs – feature in this book of incisive portraits, all beautifully sequenced with subtle visual correspondences.

“He took me to places taking photographs where I never, ever would have gone,” says celebrated writer Fran Lebowitz, who like Aletti was a close friend of Hujar and whose 1970s portrait also appears in Lost Downtown. “I went to extremely serious, very heavy S&M bars.” And it didn’t stop there. “West Side downtown there were these burnt-out piers. They were used by gay men to have sex in. They were pitch black inside … the environment was very rough and dangerous,” she adds. “Peter was physically fearless in the city, that’s for sure, when there were plenty of places that were dangerous to go in New York.”

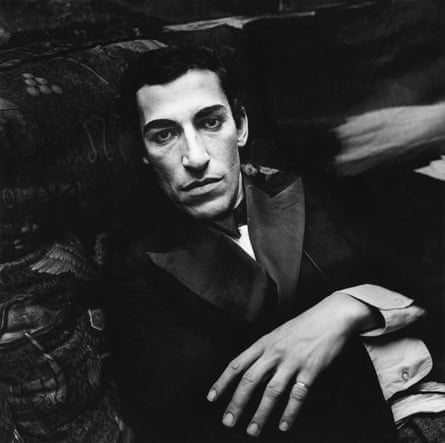

What was Hujar like? “He was charismatic and complicated and, it turned out, deeply insecure, with a damaging family history he kept mostly to himself,” continues Aletti in his pithy introduction to Lost Downtown. I ask Aletti to elaborate on “charismatic”. “A striking, tall, good-looking man who was very engaging in company,” he explains. “He was really wonderful at parties. I can’t tell you the number of times that people I knew who met him for the first time would call me and say: ‘Who was that guy? I’m in love with him.’”

“He was famously handsome,” agrees Lebowitz. “I was probably the only person that Peter ever knew who wasn’t in love with him. Everybody fell madly in love with Peter. Everybody. In love.”

And what about complicated? “Underneath all that was an incredible insecurity, an incredible sense of not getting where he wanted to be, and real anger at the way things were going in his life,” says Aletti, who also thinks Hujar’s estrangement from his family was “something from your past that continues to drain your confidence. I don’t think it was present all the time, but I think in his darkest moments, it was something that shadowed him.”

But far from becoming embittered towards the world, Hujar became a father figure to younger artists such as Gary Schneider, who was an aspiring young photographer when he got to know Hujar in the early 1980s. “He was a mentor to many artists of my generation. He was 20 years our senior. People like Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz, and [sculptor] Kiki Smith … He championed their work and he was very connected to them.”

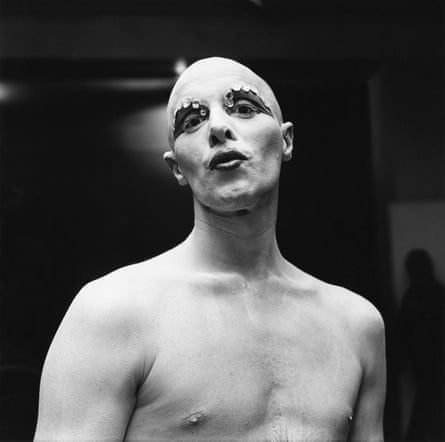

As a fellow photographer, Schneider sees a piercing, penetrating quality in Hujar’s portraits. “His ability to connect with his subject is so powerful,” he says. “How unveiled the portraits are is something I’m interested in as an artist … Even though the work is very designed … there’s a moment of powerful connection with his subject. And that’s unusual.”

Aletti picks out a specific example of this photographic connection. “His many pictures of David Wojnarowicz,” he says. “There was a real reaching out, I think, and a real loving and understanding quality in those pictures. I remember being very struck by them in the beginning because when I met David I didn’t think he was particularly impressive … But when I saw Peter’s pictures of him I completely understood what Peter saw in him.”

What was it like to be photographed by Hujar? “I hate getting my picture taken, and I always did. But I didn’t really mind it with Peter,” says Lebowitz. “Peter was, in a way, at his most moving when taking photographs. He was so absorbed by it. Peter was in many ways a very tortured man, and I felt like when he was taking photographs, he wasn’t. I had other friends who were photographers, but not like Peter. Peter was so profoundly absorbed and engaged by it. He was never not a photographer.”

It seems strange that such a talented, charming and committed photographer was not more successful during his lifetime. Schneider explains succinctly: “He certainly didn’t work well with most galleries and collectors. So he kept himself in poverty,” he says. “He often worked against his supporters.”

One lasting success Hujar did achieve in his lifetime was the publication of a book in 1976, Portraits in Life and Death, long out of print. It is an unusual book: a sequence of masterly portraits of Hujar’s friends and associates is followed by a set of pictures of corpses in the catacombs underneath an Italian church. Perhaps inspired by this, Sontag wrote in the book’s introduction: “Photography also converts the whole world into a cemetery,” prefiguring one of the key themes in French thinker Roland Barthes’s seminal 1980 essay about photography, Camera Lucida.

Hujar was also an inspiration for the younger photographers who knew him, such as Goldin and Robert Mapplethorpe, but not in a direct way. “Nan clearly was a friend, but her work looks nothing like Peter’s,” says Aletti. “And again, Mapplethorpe’s work looks nothing like Peter’s for the most part. What I value in Peter’s work I find absent in Mapplethorpe’s, which is a kind of soulfulness, and a real desire for connection … But I think, in a way, because Peter was a cult character during his lifetime, that he didn’t have much influence on his contemporaries, that I can think of. But I think he’s much more understood and much more seen now, and his influence is hopefully still growing.”

This slow-burn of success explains why Hujar is gradually becoming more appreciated decades after his death. “He was kind of anti-institution, Peter. He even talked about how he would have to die for the work to become famous,” says Schneider. “And it was really true.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion