In a unique experiment, The Guardian published online the full manuscript of its major investigation into the climate science emails stolen from the University of East Anglia, which revealed apparent attempts to cover up flawed data; moves to prevent access to climate data; and to keep research from climate sceptics out of the scientific literature.

As well as including new information about the emails, we allowed web users to annotate the manuscript to help us in our aim of creating the definitive account of the controversy. This was an attempt at a collaborative route to getting at the truth.

We hoped to approach that complete account by harnessing the expertise of people with a special knowledge of, or information about, the emails. We wanted the protagonists on all sides of the debate to be involved, as well as people with expertise about the events and the science being described or more generally about the ethics of science. The only conditions are the comments abide by our community guidelines and add to the total knowledge or understanding of the events.

The annotations - and the real name of the commenter - were added to the manuscript, initially in private. The most insightful comments were then added to a public version of the manuscript. We hoped the process would be a form of peer review.

Scientists sometimes like to portray what they do as divorced from the everyday jealousies, rivalries and tribalism of human relationships. What makes science special is that data and results that can be replicated are what matters and the scientific truth will out in the end.

But a close reading of the emails hacked from the University of East Anglia in November exposes the real process of everyday science in lurid detail.

Many of the emails reveal strenuous efforts by the mainstream climate scientists to do what outside observers would regard as censoring their critics. And the correspondence raises awkward questions about the effectiveness of peer-review - the supposed gold standard of scientific merit - and the operation of the UN's top climate body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The scientists involved disagree. They say they were engaged not in suppressing dissent but in upholding scientific standards by keeping bad science out of peer-reviewed journals. Either way, when passing judgment on papers that directly attack their own work, they were mired in conflicts of interest that would not be allowed in most professions.

The cornerstone of maintaining the quality of scientific papers is the peer review system. Under this, papers submitted to scientific journals are reviewed anonymously by experts in the field. Conducting reviews is seen as part of the job for academics, who are generally not paid for the work.

The papers are normally sent back to the authors for improvement and only published when the reviewers give their approval. But the system relies on trust, especially if editors send papers to reviewers whose own work in being criticised in the paper. It also relies on anonymity, so reviewers can give candid opinions.

Cracks in the system have been obvious for years. Yesterday it emerged that 14 leading researchers in a different field - stem cell research - have written an open letter to journal editors to highlight their dissatisfaction with the process. They allege that a small scientific clique is using peer review to block papers from other researchers. Many will see a similar pattern in the emails from UEA's Climatic Research Unit, which brutally expose what happens behind the scenes of peer review and how a chance meeting at a barbeque years earlier had led to one journal editor being suspected of being in the "greenhouse sceptics camp".

The head of the CRU, Professor Phil Jones, as a top expert in his field, was regularly asked to review papers and he sometimes wrote critical reviews that might have had the effect of blackballed papers criticising his work. Here is how it worked in one case.

A key component in the story of 20th century warming is data from sparse weather stations in Siberia. This huge area appears to have seen exceptional warming of up to 2C in the past century. But in such a remote region, actual data is sparse. So how reliable is that data, and do scientists interpret it correctly?

In March 2004, Jones wrote to Professor Michael Mann, a leading climate scientist at Pennsylvania State University saying that he had

"recently rejected two papers [one for the Journal of Geophysical Research and one for Geophysical Research Letters] from people saying CRU has it wrong over Siberia. Went to town in both reviews, hopefully successfully. If either appears I will be very surprised." He did not specify which papers he had reviewed, nor what his grounds for rejecting them were. But the Guardian has established that one was probably from Lars Kamel a Swedish astrophysicist formerly of the University of Uppsala. It is the only paper published on the topic in the journal — or indeed anywhere else — that year.

Kamel analysed the temperature records from weather stations in part of southern Siberia, around Lake Baikal. He claimed to find much less warming than Jones, despite analysing much the same data. Kamel told the Guardian: "Siberia is a test case, because it is supposed to be the land area with most warming in the 20th century." The finding sounded important, but his paper was rejected by Geophysical Research Letters (GRL) that year.

Kamel was leaving academic science and never tried to publish it elsewhere. But the draft seen by the Guardian asserts that the difference between his findings on Siberia temperatures and that of Jones is "probably because the CRU compilation contains too little correction for urban warming." He does not, however, justify that conclusion with any detailed analysis.Kamel says he no longer has a copy of the anonymous referee judgments on the paper, so we don't know why it was rejected. The paper could be criticised for being slight and for not revealing details about its methods of analysis. A reviewer such as Jones would certainly have been aware of Kamel's views about mainstream climate research, which he had called "pseudo-science". He would also have known that its publication in a journal like GRL would have attracted the attention of professional climate sceptics. Nonetheless, the paper raised important questions about the quality of CRU's Siberian data, and was a rare example of someone trying to replicate the Jones's analysis. On those grounds alone, some would have recommended its publication.

Kamel's paper admits the discrepancy "does not necessarily mean the CRU surface record for the entire globe is in error." But it argues that the result suggests it "should be checked in more regions and even globally." Phil Jones was not able to comment on the incident.

Critics of Jones such as the prominent scpetical Stephen McIntyre, who runs the Climate Audit blog have long accused him of preventing critical research from having an airing. McIntyre wrote on his web site in December: "CRU's policies of obstructing critical articles in the peer-reviewed literature and withholding data from critics have unfortunately placed issues into play that might otherwise have been settled long ago." He also says obstructing publication undermine claims that all is well in scientific peer review.

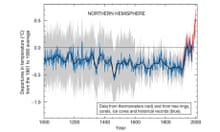

Dr Myles Allen a climate modeller at the University of Oxford and Prof Hans von Storch, a climate scientist at the Institute for Coastal Research, in Geesthacht, Germany signed a joint column in Nature when the email hacking story broke, in which they said that "no grounds have arisen to doubt the validity of the thermometer-based temperature record since it began in about 1850." But that argument is harder to make if such evidence, flawed though it might be, is actively being kept out of the journals.

In another email exchange CRU scientist Dr Keith Briffa initiates what looks like an attempt to have a paper rejected. In June 2003, as an editor of an unnamed journal, Briffa emailed fellow tree-ring researcher Edward Cook, a researcher at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York, saying "Confidentially I now need a hard and if required extensive case for rejecting [an unnamed paper] – to support Dave Stahle's and really as soon as you can. Please." Stahle is a tree-ring professor from the University of Arkansas. This request appears to subvert the convention that reviewers should be both independent and anonymous.

Cook replied later that day: "OK, today. Promise. Now, something to ask from you." The favour was to provide some data to help Cook review a paper that attacked his own tree-ring work. "If published as is, this paper could really do some damage," he said. "It won't be easy to dismiss out of hand as the math appears to be correct theoretically, but it suffers from the classic problem of pointing out theoretical deficiencies, without showing that their improved [inverse regression] method is actually better in a practical sense."

Briffa was unable to comment. Cook told the Guardian: "These emails are from a long time ago and the details are not terribly fresh in my mind."

In March 2003, Mann discussed encouraging colleagues to "no longer submit [papers] to, or cite papers in" Climate Research. He was angry about that journal's publication of a series of sceptical papers "that couldn't get published in a reputable journal", according to Mann. His anger at the journal had evidently been building for some time, but was focussed in 2003 on a paper published in January that year and written by Harvard astrophysicists Willie Soon and Sallie Baliunas. The pair claimed that Mann's famous hockey stick graph of global temperatures over the last 1000 years was wrong. After analysing 240 studies of past temperatures from tree rings and other sources, they said "the 20th century is neither the warmest century over the last 1000 years, nor is it the most extreme". It could have been warmer a thousand years before, they suggested.

Harvard press-released the paper under the headline "20th century climate not so hot", which would have pleased lobbyists against the climate change consensus from the American Petroleum Institute and George C Marshall Institute, both of which had helped pay for the research.

Mann told me at the time the paper was "absurd, almost laughable". He said Soon and Balunias made no attempt in the paper to show whether the warmth they found at different places and times round the world in past eras were contemporaneous in the way current global warming is. If they were just one-off scattered warm events they did not demonstrate any kind of warm era at all. Soon did not respond to Guardian Requests to discuss the paper.

The emails show Mann debating with others what he should do. In March 2003, he told Jones: "I believed our only choice was to ignore this paper. They've already achieved what they wanted - the claim of a peer-reviewed paper. There is nothing we can do about that now, but the last thing we want to do is bring attention to this paper."

But Jones told Mann: "I think the skeptics will use this paper to their own ends and it will set [the field of paleoclimate research] back a number of years if it goes unchallenged." He was right. The Soon and Balunias paper was later read into the Senate record and taken up by the Bush administration, which attempted to get it cited in a report from the Environmental Protection Agency against the wishes of the report's authors.

Persuaded that the paper could not be ignored, Mann assembled a group of colleagues to review it. The group included regular CRU emailers Jones, Dr Keith Briffa, Dr Tom Wigley and Dr Kevin Trenberth. They sent their findings to the journal's editorial board, arguing that Soon's study was little more than anecdote. It had cherry-picked data showing warm periods in different places over several centuries and had provided no evidence that they demonstrated any overall warming of the kind seen in the 20th century.

The emails reveal that when the journal failed to disown the paper, the scientists figured a "coup" had taken place, and that one editor in particular, a New Zealander called Chris de Freitas, was fast-tracking sceptical papers onto its pages. Mann saw an irony in what had happened. "This was the danger of always criticising the sceptics for not publishing in the peer-reviewed literature. Obviously, they found a solution to that - take over a journal!"

But Mann had a solution. "I think we have to stop considering Climate Research as a legitimate peer-reviewed journal. Perhaps we should encourage our colleagues... to no longer submit to, or cite papers in, this journal. We would also need to consider what we tell or request of our more reasonable colleagues who currently sit on the editorial board."

Was this improper pressure? Bloggers responding to the leaking of these emails believe so. Mann denies wanting to "stifle legitimate sceptical views". He maintains that he merely wanted to uphold scientific standards. "Please understand the context of this," he told The Guardian after the scandal broke. "This was in response to a very specific, particularly egregious incident in which one editor of the journal was letting in a paper that clearly did not meet the standards of quality for the journal."

But many on the ten-man editorial board agreed with Mann. There was a revolt. Their chief editor von Storch wrote an editorial saying the Soon paper shouldn't have appeared because of "severe methodological flaws". After their publisher Otto Kinne refused to publish the editorial, von Storch and four other board members resigned in protest. Subsequently Kinne himself admitted that publication had been an error and promised to strengthen the peer-review process. Mann had won his argument.

Sceptical climatologist and Cato Institute fellow Pat Michaels alleged in the Wall Street Journal in December last year that the resignations by von Storch and his colleagues were a counter-coup initiated by Mann and Jones. This is vehemently denied by von Storch. While one of the editors who resigned was a colleague of Jones at CRU, von Storch had a track record of independence. If anything, he was regarded as a moderate sceptic. Certainly, he had annoyed both mainstream climate scientists and sceptics.

Also writing in the Wall Street Journal in December, he said: "I am in the pocket of neither Exxon nor Greenpeace, and for this I come under fire from both sides – the sceptics and alarmists – who have fiercely opposing views but are otherwise siblings in their methods and contempt.... I left the post [as chief editor of Climate Research] with no outside pressure, because of insufficient quality control on a bad paper – a sceptic's paper, at that."

The bad blood over this paper lingered. A year later in July 2004, Jones wrote an email to Mann about two papers recently published in Climate Research - the Soon and Balunias paper and another he identified as by "MM". This was almost certainly a paper from Canadian economist Ross McKitrick and Michaels that returned to an old sceptics' theme. It claimed to find urbanisation dominating global warming trends on land. Jones called it "garbage". More damagingly, he added in an email to Mann with the subject line "HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL".

"I can't see either of these papers being in the next IPCC report. Kevin [TRENBERTH] and I will keep them out somehow - even if we have to redefine what the peer-review literature is!"

This has, rightly, become one of the most famous of the emails. And for once, it means what it seems to mean. Jones and Trenberth, of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, had recently become joint lead authors for a key chapter in the next IPCC assessment report, called AR4. They had considerable power over what went into those chapters, and to have ruled them out in such a manner would have been a clear abuse of the IPCC process.

Today, neither man attempts to deny that Jones's promise to keep the papers out was a serious error of judgment. Trenberth told the Guardian: "I had no role in this whatsoever. I did not make and was not complicit in that statement of Phil's. I am a veteran of three other IPCC assessments. I am well aware that we do not keep any papers out, and none were kept out. We assessed everything [though] we cannot possibly refer to all literature... Both of the papers referred to were in fact cited and discussed in the IPCC."

In an additional statement agreed with Jones, he said: "AR4 was the first time Jones was on the writing team of an IPCC assessment. The comment was naive and sent before he understood the process." Some will not be content with that. The AR4 was indeed the first in which Jones had been a lead author, responsible for the content of a whole chapter. But Jones had been a contributing author to IPCC assessment reports for more than a decade and should have been aware of the rules.

Climate Research is a fairly minor journal. Not so Geophysical Research Letters, published by the august American Geophysical Union (AGU). But when it began publishing what Mann, Wigley, Jones and others regarded as poor-quality sceptical papers, they again responded angrily. GRL provided a home for one of a series of papers by McIntyre and McKitrick challenging the statistical methods used in the hockey stick analysis. When Mann's complaints to the journal were rebuffed, he wrote to colleagues in January 2005: "Apparently the contrarians now have an 'in' with GRL."

Mann had checked out the editor responsible for overseeing the papers , a Yale chemical engineer called James Saiers, and noted his "prior connection" with the same department at the University of Virginia, where sceptic Pat Michaels worked. He added, "we now know" how various other sceptically tinged papers had got into GRL. Wigley appeared to agree. "This is truly awful," he said, adding that if Mann could find "If you think that Saiers is in the greenhouse skeptics camp, then, if we can find documentary evidence of this, we could go through official AGU channels to get him ousted."

A year after the row erupted, in 2006, Saiers gave up the GRL post. Sceptics have claimed that this was due to pressure from Wigley, Mann and others. Saiers says his three-year term was up. "My departure had nothing to do with attempts by Wigley or anyone else to have me sacked," he told the Guardian. "Nor was I censured, as I have seen suggested on a blog posting written by McKitrick."

As for Mann's allegation, Saiers does not remember ever talking to Michaels "though I did attend a barbecue at his home back in the early 1990s. Wigley and Mann were too keen to conclude that I was in league with the climate-change sceptics. This kerfuffle could have been avoided if the parties involved would have done more to control their imaginations."

This article was amended on 16 January 2012. The original stated that four reviewers of the Soon and Baliunas paper for the magazine Climate Research had recommended rejection. In fact none had rejected the paper. This has been corrected.

Annotations

The text below consists of invited comments made on the Climate wars articles. They can be accessed in the main body of the article by clicking on the text to which they refer, which is highlighted in yellow.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion