Amid the present flood of accusations of sexual harassment and abuse, there’s been a strange scarcity of broader social critique. We are accumulating copious evidence of wrongdoing, without looking deeper for a diagnosis. “Boy, all men really are pigs!” isn’t close to radical enough, because the sentiment invites criticisms like the one Masha Gessen recently made: that we’re on the brink of a “sex panic,” an epidemic of puritanism that will take down innocent men out of sheer inertia. A focus on these individual incidents of harassment, and not the structure that spawns them, is a weak strategy for change. Such an approach makes it much easier for naysayers and supporters alike to combat claims of harassment one by one, by casting aspersions on accusers, or condemning individual men for their actions.

This moment is not about sex, and the problem is anything but personal. As feminists have been saying for years, sexual harassment and abuse are about power—specifically, the enormous power men still wield over women. That’s why women (and men) are naming male offenders of all political stripes, religious and atheist, rich and poor, famous and obscure. “Sexual harassment” is not an illness in and of itself; it’s a symptom of patriarchy’s persistence.

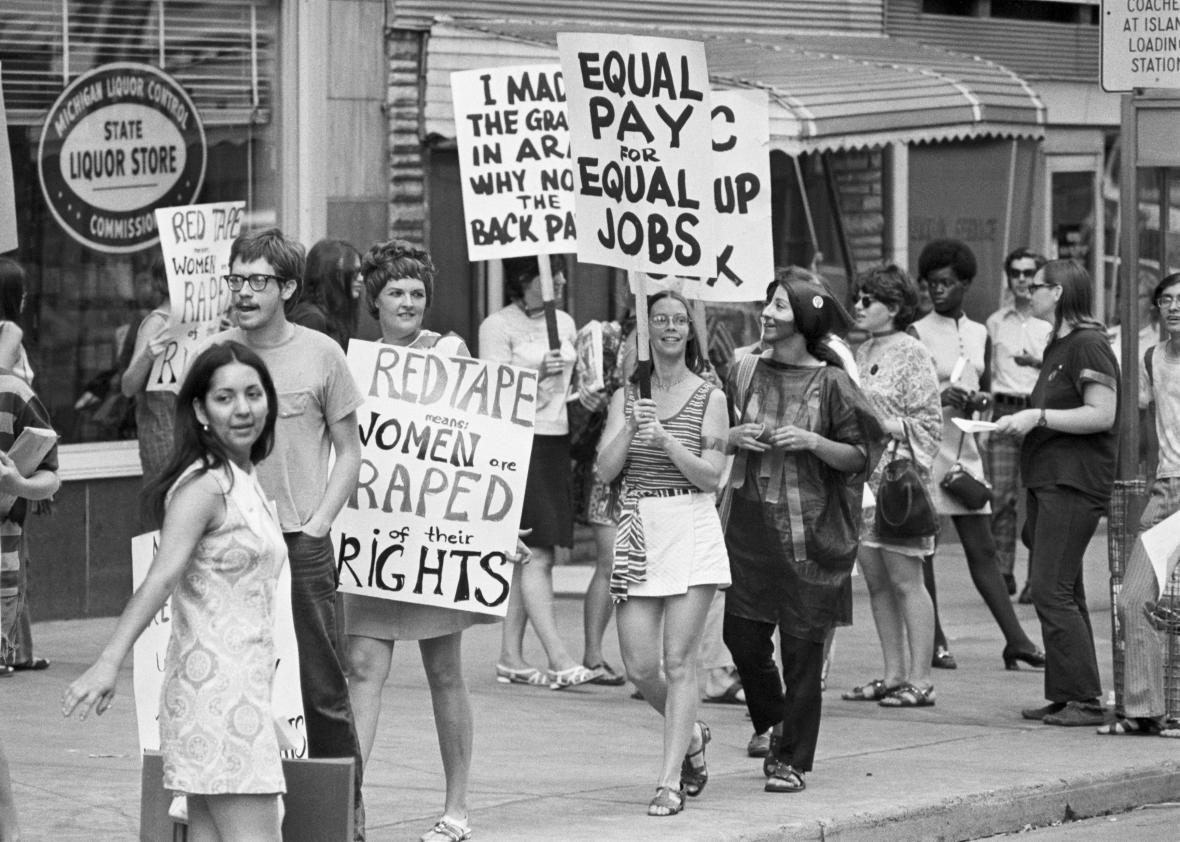

We need to be unafraid to tie sexual harassment to other forms of violence against women—to see the connections between harassment and the pay gap, the lack of good child care, and the persistence of the second shift. We need to recognize how sexual harassment and racial injustice exist in symbiosis, and to think about how workers’ tenuous position at this particular moment in the history of capitalism has enabled sexual harassment to thrive. What we need right now to go along with our ’70s-style radical rage (as Rebecca Traister recently dubbed it) is some ’70s-style feminist social analysis.

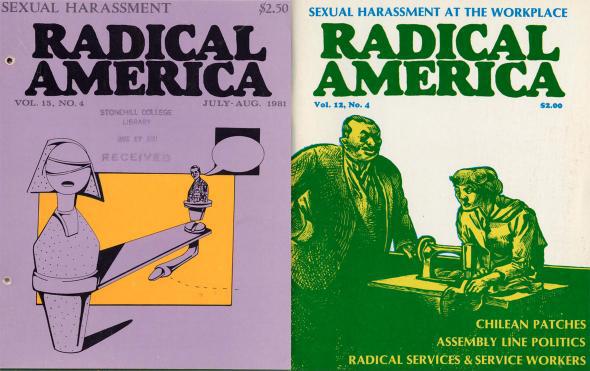

Feminists studying sexual harassment in the mid-1970s—before harassment was illegal or much a part of the public discourse—took their cues from the second-wave movement against rape, which re-theorized that crime as one of power, and not of passion. Accordingly, activists trying to understand the problem of workplace harassment characterized it as “economic rape.” “The major function of sexual harassment is to preserve the dominance of patriarchy,” Mary Bularzik, a co-founder of the group Alliance Against Sexual Coercion, wrote in the magazine Radical America in 1981. “Harassment is ‘little rape,’ an invasion of a person, by suggestion, by intimidation, by confronting a woman with her helplessness.”

Alliance Against Sexual Coercion, founded in 1976 by three co-workers at a rape crisis center in Washington, D.C., responded to an unmet need after the center started getting phone calls from female government employees whose bosses were harassing them. Freada Kapor Klein, one of the organization’s three co-founders (along with Bularzik and Lynn Wehrli), told me that it was “women themselves” who first made the connection between sexual coercion in the workplace and rape, by identifying a rape crisis hotline as the place to call.* “Despite the similarities on many levels,” Kapor Klein told me, the normal tools of the rape crisis counselor—offering women assistance with procuring medical treatment and navigating contacts with law enforcement—didn’t work. “It had no relevance to what women wanted, which was women wanted the behavior to stop, and to keep their jobs.” (Kapor Klein, who later wrote a dissertation about sexual harassment in government employment, is now a venture capitalist and activist for organizational diversity in Silicon Valley.)

The members of AASC moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and began to collect stories of harassment and conduct speak-outs on the issue. The Working Women’s Institute did similar work in New York. While helping individual women pursue court cases, consulting on government efforts to write guidelines, and training employees at corporations, activists in these two groups began to articulate a theoretical argument about why sexual harassment happens. Both groups—as historian Carrie N. Baker shows in her history of anti–sexual harassment movements in the late ’70s and early ’80s—were surprisingly successful at reaching across racial and economic lines in their activism.

Among the ideas the activists came up with was the theory, derived from women’s history, that harassment was patriarchy’s way of “keeping women in their place.” Feminist and historian Linda Gordon, writing in Radical America in 1981, thought workplace harassment functioned to discipline women who dared to violate an ideology that dated to the 19th century. In the “separate spheres” schema, men should be the ones to go out in public, to work and to socialize; good women should rely entirely on their husbands to present the family’s face to the world and be content with operating as nurturer and home administrator behind the scenes. Women who went out in public had sacrificed their right to male protection.

This persistent belief about the male public and female private spheres, the activists pointed out, also parlayed racial and class inequality into increased vulnerability to sexual harassment. Historically, women who couldn’t afford to stay at home—poorer women who also tended to be women of color—had been seen as fair game for employers’ and co-workers’ predations. Because they often lacked the social standing to combat harassment, and because stereotypes about their oversexuality abounded, women of color were at high risk of sexual coercion at the workplace.

And it was women of color who first risked bringing suit against workplace harassment. Carrie Baker makes the point that although sexual harassment has been seen as a white middle-class issue in the years since Catherine MacKinnon wrote her landmark book Sexual Harassment of Working Women, in the 1970s and early 1980s, working-class women and women of color were the ones to step forward to bring the precedent-setting first cases under Title VII. (And Mechelle Vinson, the plaintiff in Meritor v. Vinson, the 1986 Supreme Court case that established that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 should protect women from a “hostile or abusive work environment,” was black.) “Sexual harassment law grew out of the legacy of the civil rights movement by building on racial harassment precedent in the law,” Baker writes.

That relationship between racism and harassment is a point that has been lost as we’ve moved into the Michael Douglas/Disclosure period of public conversation about the issue. As Kapor Klein said when we spoke recently: “Women of color were the canaries in the coal mine, and as soon as mainstream media organizations decided there was an issue here, it quickly became a ‘gender issue,’ with absolutely no attention paid to the dynamics of racism as they interact with gender and perceptions of sexuality.”

Today’s discourse is also lacking that dimension, focused, as it mostly is, on celebrity harassment stories featuring white complainants. According to the feminists working on the problem in the ’70s, harassment was encouraged by a culture that socialized men to dominate everything around them, especially women. Lynn Wehrli, a co-founder of AASC, wrote a master’s thesis on the topic for MIT in 1977 in which she argued against the use of the word “power” to describe what’s being exercised when harassment happens. “Power itself is not ‘bad,’ though its use by particular individuals or groups may be destructive,” Wehrli wrote. “In the feminist definition, it is not power per se, but dominance or control over others which is the destructive force to be combatted.” Harassment belittles women, sometimes puts them at physical risk, and always forces them into impossible dilemmas; it’s the ultimate in domination.

Capitalism—described by feminists working on harassment as an economic system that encouraged and rewarded raw competition while affording little protection to workers—left women vulnerable to such dominance plays. AASC members Martha Hooven and Nancy McDonald wrote in an article in the magazine Aegis in 1978 that capitalism “feeds quite nicely on sexism and racism.” It forced women into situations where they might be harassed, and profited from their paralysis: “Most women have little autonomy or control over working conditions. We must answer constantly to an employer and are often powerless to change work situations. Thus, women learn to put up with sexual harassment at their jobs because they are in very real fear of losing them.”

This dynamic got worse the more economically disadvantaged the women workers were. “Logically enough,” Karen Lindsey wrote in Ms. magazine in 1977, “the women who are hardest hit by sexual harassment on the job are waitresses, clerical workers, and factory workers—women who are poorly paid to begin with and who cannot afford to quit their jobs. Their economic vulnerability is played on by their male bosses.”

Brown University Center for Digital Initiatives

Beyond creating a climate where harassment could thrive, capitalism reaped the benefits of this dynamic, since many women left male-dominated fields with higher-paying jobs for lower-paying positions in teaching, nursing, or social work where they would be less likely to have to deal with a harasser. As AASC put it in an article in Radical America in 1981: “Sexual harassment is possible because sexism is an integral part of capitalism … Occupational segregation … props up the system of depressed wages for women workers.”

If you think we have moved beyond the embedded problems that second-wavers identified as the root of sexual harassment, think again. To find vestiges of separate-spheres ideology, read a hashtag like #ThxBirthControl, with tweets divided between liberals praising birth control for giving women the power to attain higher education, travel the world, and work their way up the career ladder, and conservatives calling such public-sphere goals “self-centered.” The belief that women really shouldn’t be working and making money alongside men undergirds such diverse annoyances as Rush Limbaugh’s critique of day care, the MRA fixation on marrying “submissive” wives from poorer countries, and Donald Trump Jr.’s comment that women who can’t “handle” sexual harassment should “drop out of the workforce” and become kindergarten teachers.

Other social factors that went hand in hand with harassment in the ’70s persist, or in some cases, are even worse now than they were then. Are women of color still disrespected and even more underpaid than white women? Yep. Do workers of all kinds still labor without much protection? Even more do now than in the ’70s, and those in more precarious jobs feel the threat of harassment more acutely. Are men still taught to dominate, and to respect those who perform dominance? You betcha. And the behavior continues to function as a check on women’s ambitions. Sociologist Heather McLaughlin tallies up the financial effects of sexual harassment, finding that a large percentage of harassed women quit their jobs; many of them start over in different careers, or take jobs they wouldn’t necessarily have wanted, because they perceive the industry as less harassment-friendly.

In the late ’70s, AASC used its theories about sexual harassment as part of its public education efforts, inviting women to understand not only that what they were going through was wrong, but also that it was connected to other problems of patriarchy. “Men are socialized to dominate women through the use and threat of violent behavior,” AASC wrote in a 1977 pamphlet. “Most men’s opportunities for economic success are limited. So the most expedient way for a man to gain a sense of self becomes through asserting superiority over women.” Capitalism was part of the problem, the activists told readers: “Sexist attitudes, along with racist and classist beliefs, are vital parts of the U.S. economic system.”

Those of us who want change should be unafraid to talk about harassment in such theoretical terms today. If you don’t agree with AASC’s ideas about the relationship between patriarchy and capitalism, that’s fine. (Lin Farley, another activist who wrote the first popular-press book on the problem in 1978, thought sexual harassment put the two systems at odds with each other.) But it seems fruitful to at least have the conversation.

“The government and other institutions forced by our pressure to deal with sexual harassment” would like nothing more than to separate the issue from “the larger political struggle against male supremacy,” Linda Gordon wrote in Radical America in 1980. “They will want to take control out of our hands, and to transform the issue into a bureaucratized, mechanistic set of procedures for disallowing certain very narrowly defined behavior.” They did just that, and we’re paying the price.

*Update, Nov. 21 2017: This article has been updated to reflect Freada Kapor Klein’s full name.