Red alert: Doubts linger over Interpol’s Chinese boss ahead of Beijing meet

Police organisation prepares for first general assembly in China since 1995

Intrigue, infighting and cynical horse-trading aside, in a one-party state like China the most important meeting of the tightly controlled political calendar is the one which puts in place those at the very top of the ruling structure.

But another, much less trumpeted, gathering is due to take place in the capital a month or so before that. And it may well have far-reaching ramifications for China, and the rest of an increasingly uncertain world.

What’s an Interpol red notice and what power does it wield over wanted Chinese tycoon Guo Wengui?

In late September – for only the second time in its history – China will host the general assembly of the international police organisation, Interpol. Law enforcers from the organisation’s 190 member countries last met in Beijing in 1995.

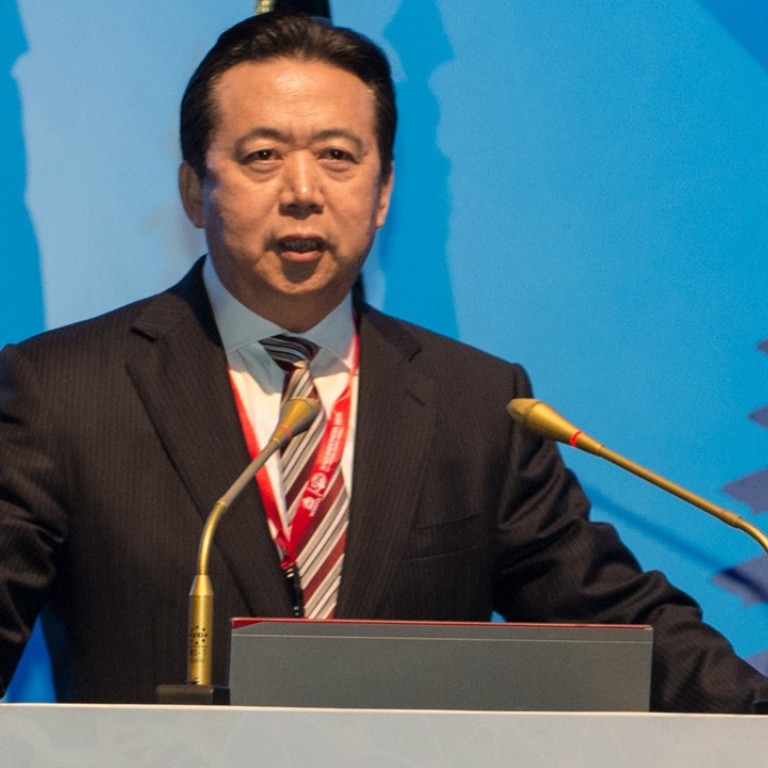

Back then, the world was a very different place. And in a powerful emblem of changed times, delegates to Interpol’s 86th assembly will gather around its first Chinese president, Meng Hongwei, who was unanimously elected at last year’s meeting in Indonesia.

The election of China’s vice-minister of public security has been met with disquiet in some quarters over how China’s unique, and often opaque, legal and judicial systems will dovetail with an international system of norms rooted in a Western liberal consensus of what law and order look like.

High on the list of worries is the potential for abuse of Interpol’s red notice system of international warrants, through which member countries request to Interpol headquarters in France that a person they deem a criminal fugitive be put on a list for arrest pending extradition should they turn up in another member country.

As it stands, the red notice system is largely based on good faith. Critics of the system say it is open to abuse and have accused not only China but Russia and Iran, among others, of using it to target political opponents and dissidents under the guise of criminal investigation.

With Meng at the very top of Interpol, critics fear scrutiny of China’s applications for red notices could, at best, be less than thorough.

But an Interpol spokesman said criticism of Meng’s election stemmed from confusion about the exact nature of his role, which is more ceremonial than substantial.

“The president of the organisation heads its executive committee and is elected by the general assembly for a period of four years. He presides at meetings of the general assembly and the executive committee and directs the discussions,” the spokesman said.

And the Interpol’s secretary general, said the spokesman, “is effectively the organisation’s chief full-time official. He or she is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day work of international police cooperation.”

Indeed, making his first major address as president at an Interpol conference in Singapore earlier this month, Meng sounded more the bridge builder than master subverter.

He signalled China was in the business of cooperation in the increasingly complex global fight against crime and corruption.

Meng appeared to endorse a multinational approach to the hot-button issue of cybercrime, broadly in line with that favoured by the United States and its allies.

“No single country or profession can rely solely upon its own capability to address the problem [of cybercrime]. Collaboration should not be limited to law enforcement agencies. Contributions from leaders and experts in different professions are equally crucial,” he said.

David Hickson, a former US federal prosecutor who indicted five professional hackers from a People’s Liberation Army unit for online theft of intellectual property from US companies, said he “took heart” from Meng’s speech.

He told the CyberScoop website: “I took great heart when I read [Meng’s] speech, because it looks like the campaign… to enforce the rule of law in the digital space is bearing fruit.”

But James Lewis, senior vice-president of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a US-based think tank, struck a note of caution, saying it was “too soon to tell” if Meng’s words would be reflected in China’s behaviour. ■